Introducing Belfast’s Bonnie Burns

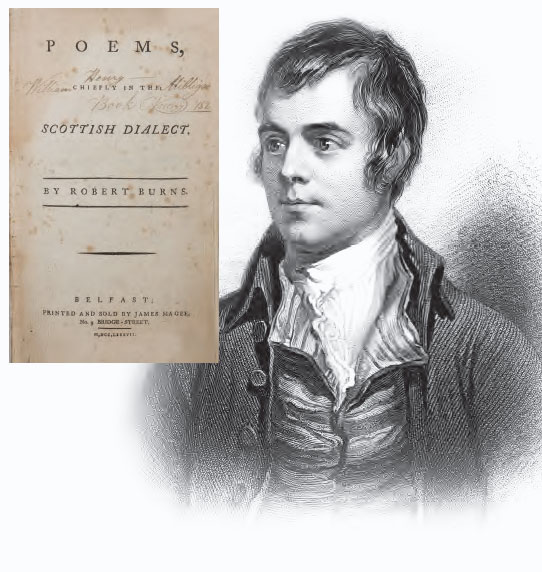

1786–1787: Published and Pirated

Individual poems by Burns were printed in Belfast newspapers in 1786 and his first book was published in rural Kilmarnock in July of that year. It sold like wildfire – and sophisticated Edinburgh produced an enlarged edition in 1787. The demand in Ulster inspired the entrepreneurial Belfast printer James Magee of Bridge Street to produce a cheaper pirate edition, which was announced in the Belfast News Letter on 24 September 1787.

Rumoured sightings

Like any celebrity, there were traditions of sightings of Burns. Almost a century later, in 1894 the Ulster Journal of Archaeology published a series of letters asking readers if they knew anything of Burns’ reputed visits to north east Antrim. There is also a County Down legend of Burns visiting Donaghadee on a day trip to see a fellow poet who had invited him to “visit to a part of Ulster where there were very many of Scotch descent, his warm admirers.”

The 1787 Belfast edition Courtesy Linen Hall Library

Songs and Melodies

Burns’ work collecting traditional songs also had an Ulster dimension, and he wrote of the common musical culture and community on both sides of the water – “the wandering minstrels, harpers and pipers, used to go frequently errant through the wilds both of Scotland and Ireland and so some favourite airs might be common to both.”

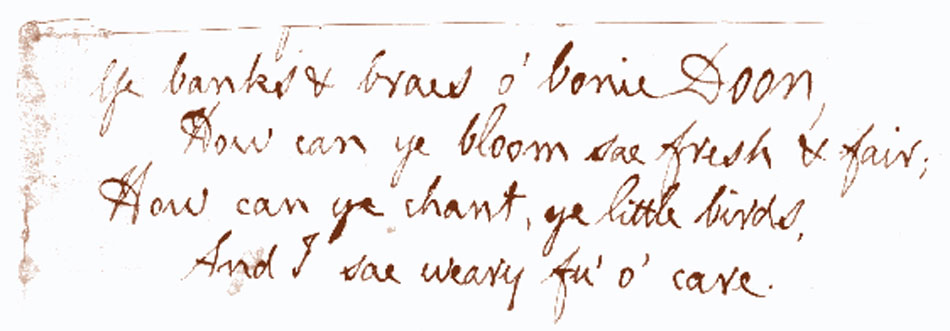

Of the tune ‘Jockie’s Gray Breeks’ he wrote that “though this has certainly every evidence of being a Scottish air, yet there is a well known tune and song in the north of Ireland called ‘The Weaver and His Shuttle O’ which though sung much quicker is, every note, the very tune.” He wrote that the melody for ‘Ye Banks and Braes of Bonnie Doon’ was more than likely from Ireland, asking a correspondent “What would you think of Scots words to some beautiful Irish airs?”

Robert Burns’ manuscript for ‘Ye Banks and Braes o’ Bonie Doon’

1794: Ulster visitors

By 1794 Burns was living in a fine red sandstone house in Dumfries, and was visited there by a series of Ulster travellers. The poet Samuel Thomson visited in February, and gave Burns a gift of Dublin snuff. In July of that year, Henry Joy, the owner of the Belfast News Letter, and Rev. William Bruce, the Presbyterian principal of Belfast Academy, visited him in Dumfries. Another Ulsterman, Luke Mullan, visited Burns in Edinburgh in 1796, just weeks before the bard died on 21 July.

Agnes Burns Cottage & Visitor Centre Stephenstown Pond, Dundalk

1796: Ulster Memorials

The Belfast News Letter and Northern Star printed obituaries to Burns, an account of his funeral procession in Dumfries, and in the weeks that followed printed more of his poems. The Ballycarry poet James Orr composed a memorial poem entitled ‘Elegy on the Death of Mr Robert Burns’ –

Sad news! He’s gane, wha baith amus’d

The man o’ taste, an’ taught the rude

Whase warks hae been mair read an’ roos’d

Than onie, save the word o’ Gude

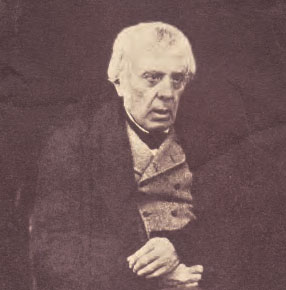

Robert Burns Jr.

1800s: The Burns family in Belfast, Dublin and Dundalk

Robert Burns Jr. visited Belfast a number of times in the 1840s; his daughter Eliza, and her daughter Martha, lived in Belfast for almost 25 years – firstly just off York Street and later on the Lisburn Road.

Burns’ nephew, Gilbert Burns, moved to Dublin in the 1840s and lived at Castleknock where he died in 1881. Burns’ sister Agnes moved to Dundalk with her husband William Galt in 1817. Their cottage is still there today, as are their graves, and also an obelisk to Burns’ memory which was built in 1859.

Robert Burns’ great granddaughter Martha, who lived in Belfast for almost 25 years, including for a time at Wilmont Terrace on the Lisburn Road

1859 & 1896 Centenary Celebrations

Robert Burns’ life and work has been part of cultural life in Ulster ever since his early poems. There were centenary events in Belfast, of his birth in 1859, and of his death in 1896. Martha and Eliza took part in these events.

1900s: A Continuing Tradition

Burns suppers settled in as part of our annual cultural calendar. A generation later, in his 1921 autobiography An Ulster Childhood, County Down author Lynn C. Doyle (Leslie Montgomery) included a chapter about the cross-community appeal of Burns. Also in 1921, Harland & Wolff paid for a monument to Burns in Failford, Ayrshire. A new Belfast Burns Association was founded in 1931, and paid for the restoration of the Dundalk obelisk in 1935.

Belfast Corn Exchange hosted a Burns centenary event in 1859. Today it is the Discover Ulster-Scots Centre

1950s: The new Ulster arts scene

In the 1950s, a new generation of prominent people in the Ulster arts scene, such as Sam Henry, Nesca Robb and Sam Hanna Bell all referenced Robert Burns, and used Ulster-Scots naturally within their own writings. Their friend John Hewitt recalled that “Once upon a time there was a copy of Burns Poems in every cottage from Comber to Ballymoney, many of them especially printed in Belfast for the local market” (Belfast Telegraph, 10 March 1955). The Irish News published a poem in 1952 which said:

“Nights with Burns are all the fashion”

Said the host, “our Province o’er

Bonnie Scotland is our passion

Ulster Scots we, to the core”

It was reprinted in Lays of An Ulster Paradise in 1960.

Doyle (1921) and Bell, Robb and Hewitt (1951)

1959 Centenary Celebrations

Belfast marked Burns’ bicentenary by inviting Scottish rugby legend John Bannerman to the city, and organising an exhibition at Linen Hall Library, film screenings and tv broadcasts.

1960s, 70s and 80s

Burns suppers continued to fill hotels and keep pipers busy. Queen’s University ran a special Burns workshop day, and Ulsterbus offered three day trips to Burns Country for £12. One Belfast butcher sold 3800lbs of haggis in the run up to Burns Night in 1978!

Seamus Heaney’s Understanding and Appreciation

Seamus Heaney recognised the value of Ulster-Scots and of the writings of Robert Burns. Having been raised in rural Ulster, and having won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995, his 1996 Burns Art Speech and his 2009 poem A Birl for Burns are outstanding examples of cultural understanding and expression.

“Burns speaks to a part of me that would prefer to crack rather than lecture... that older rhyme world which was still vestigially present when I was growing up in rural Ulster”

Seamus Heaney, Burns Art Speech, 1996

A Continuing Tradition

Burns’ versatility is part of his wide appeal. You may be a purist devotee of Burns’ language and writings, or perhaps you stumble through Auld Lang Syne on New Year’s Eve. Whether you enjoy the formal ceremony of a traditional Burns Supper, or prefer a battered haggis supper with chips, Robert Burns continues to attract new audiences and new generations – back in Scotland, here in Ulster and around the world.

Lays of an Ulster Paradise

Irish News, (1960)

Conuty Down, 1843

“...the lowland or Ayrshire dialect was commonly spoken all over the county ... in and near Ballynahinch, Dromara, Saintfield, Comber, Killinchy, Holywood, Bangor, Newtownards, Donaghadee, Kirkcubbin, Portaferry &c.

The nearness of this county to the Mull of Galloway has made the districts on the two sides scarcely distinguishable and the stream of Scottish population can be traced most distinctly from Donaghadee and Bangor upwards to the interior. In the eastern part of the parish of Hillsborough the Scottish dialect and religion are still preserved...” – from Ireland: Its Scenery, Character &c.

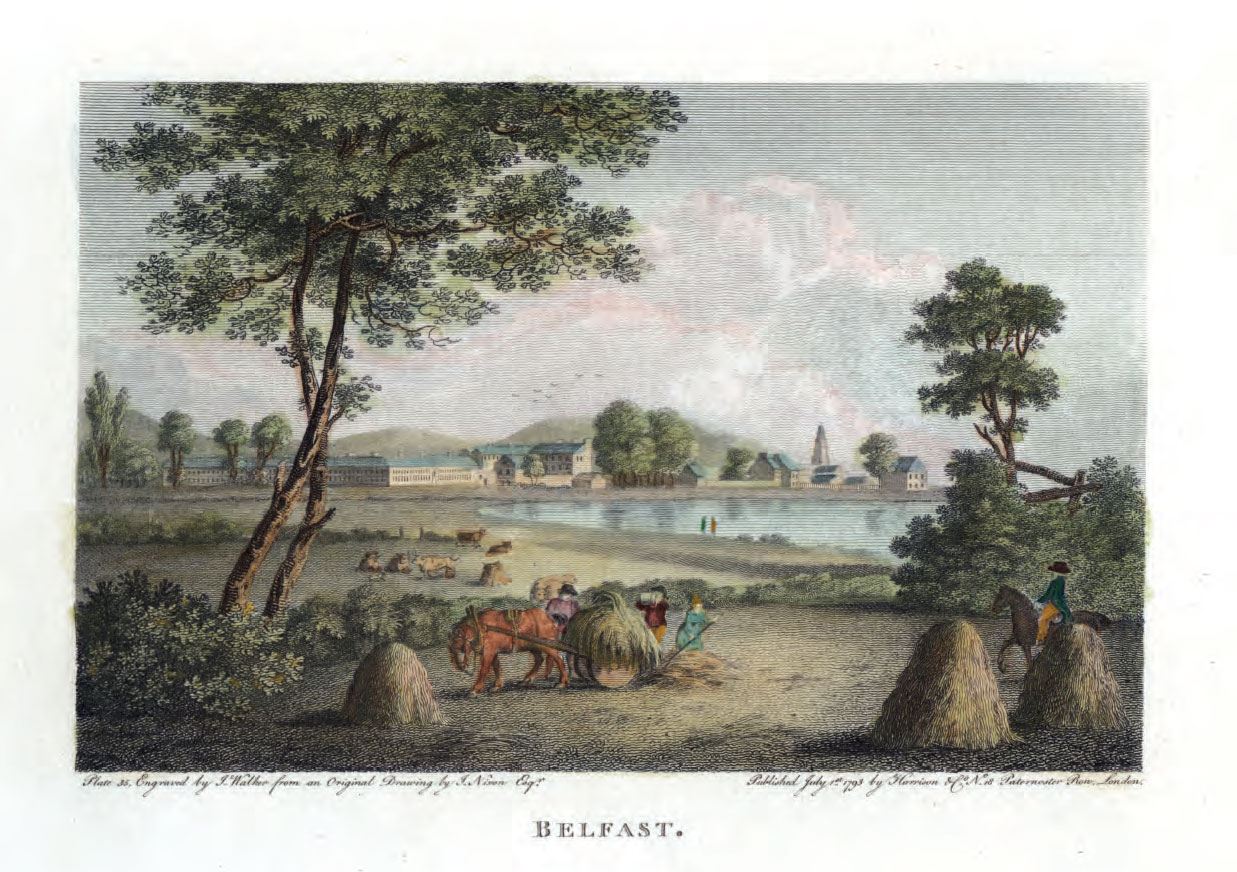

Belfast circa 1793