Ulster Covenant Belfast

Background to the Covenant

The strong social, economic, religious and cultural ties that existed between Ulster and Scotland led to an increasing consciousness of an Ulster-Scots identity in the course of the nineteenth century.

This was reinforced through the publication of histories of Presbyterianism and books such as John Harrison’s The Scot in Ulster (1888) and J.B. Woodburn’s The Ulster Scot (1914). In 1912 the US Ambassador, Whitelaw Reid, whose ancestors had come from County Tyrone, delivered a lecture in both Belfast (at the Presbyterian Assembly Buildings) and Edinburgh entitled ‘The Scot in America and the Ulster-Scot’, which was later published as a book. The Unionist leaders drew on the distinctiveness of Ulster-Scots identity in justifying their opposition to Home Rule. For example, Thomas Sinclair argued that ‘there is no homogeneous Irish nation’, pointing out that ‘Ireland today consists of two nations’.

Sinclair was one of the organisers of the Presbyterian Convention that met in Belfast on 1 February 1912. The purpose of this gathering was to make clear to the people of England and Scotland, especially Nonconformists like themselves, that the Presbyterians of Ireland were overwhelmingly opposed to Home Rule. This was to counter the false impression being given by Home Rulers that opposition to their plans was really only to be found among the Anglican landlords.

Search the Ulster Covenant

Visit the Public Records Office Northern Ireland (PRONI) to search the database of signatories of the Ulster Covenant.

While the organisers would have liked to have had one single venue where everyone could gather, this was not possible because of the numbers expected to attend. There were a reported 47,000 applications for tickets and in the end meetings were held at several locations in Belfast.

An editorial that appeared in the Presbyterian newspaper, The Witness, prior to the Convention set out very clearly the basis of their actions:

“The Irish Presbyterians desire to appeal in the first instance to Scottish Presbyterians. One of the resolutions makes a special reference to the Scottish Settlement and a special appeal to the Scottish Presbyterians, not to desert the descendants of those who were sent over to plant Ulster, and leave them to the uncovenanted mercies of Mr Redmond and the Irish Romanists who threaten them with the strong arm because they are true to Scottish traditions, Scottish religion, and Scottish associations …”

It is hardly surprising, therefore, that episodes in Scottish history should have provided the inspiration for the Ulster Covenant.

Whitelaw Reid

Presbyterian Anti-Home Rule Convention

Origins of The Covenant

The strength of the popular opposition to Home Rule led some to put forward the idea of an solemn oath or pledge that would be taken by all Unionists. James Craig was given the task of producing this. In his book, Ulster’s Stand for the Union (1922), Ronald McNeill, an Ulsterman who was MP for a Kent constituency, recounts how the idea for a covenant came about:

“Captain James Craig happened to be occupying himself one day at the Constitutional Club in London with pencil and paper, making experimental drafts that might do for the proposed purpose, when he was joined by Mr B.W.D. Montgomery, Secretary of the Ulster Club in Belfast, who asked what he was doing. “Trying to draft an oath for our people at home,” replied Craig, “and it’s no easy matter to get at what will suit.” “You couldn’t do better,” said Montgomery, “than take the old Scotch Covenant. It is a fine old document, full of grand phrases, and thoroughly characteristic of the Ulster tone of mind at this day.” Thereupon the two men went to the library, where, with the help of the club librarian, they found a History of Scotland containing the full text of the celebrated bond of the Covenanters …”

“Was bragging a characteristic of the Ulster Scot? Was it by bragging that they won Derry, Aughrim and the Boyne?”

Sir Edward Carson, Portadown, 25 September 1912

The initial idea was simply to adapt the wording of this covenant, but it was soon realised that its language and length made it unsuitable for the present situation. Nonetheless, the idea for a covenant persisted and the task of preparing the text was taken up by Thomas Sinclair. After widespread consultation and input from the Protestant churches, the final wording was agreed and on 19 September 1912 Carson read the text of the Covenant from the steps of Craigavon House. By this time, it had been agreed that 28 September would be ‘Ulster Day’ and preparations for marking it were well underway. Throughout Ulster (and beyond) venues for signing the Covenant (and the accompanying Women’s Declaration) were identified. In Belfast the Covenant would be signed in the magnificent surroundings of City Hall. In order to raise heighten interest in Ulster Day, an extensive Covenant Campaign was undertaken, starting in Enniskillen and culminating eleven days later in a massive rally at the Ulster Hall in Belfast on the eve of Ulster Day.

“You couldn’t do better than take the old Scotch Covenant. It is a fine old document”

B.W.D. Montgomery

Ulster Club, Belfast

Ulster Day in Belfast

The inhabitants of Belfast awoke on 28 September to find a crisp, bright autumn morning. J.L. Garvin, the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, reported:

“It was like another Sabbath. All shops were shut. All work was stopped. From early morning the streets began to fill, and through the surrounding crowds the Orange and other Unionist clubs marched with measured tramping: Belfast democracy had sacrificed its day’s pay as a beginning.”

Throughout Belfast religious services were held in the morning. The moderator of the Presbyterian Church, Rev. Dr Montgomery, delivered an address at the Assembly Hall, in which he spoke of the roots of most of his listeners: ‘The large majority of us here today look back to a Scottish ancestry; we cherish the same faith and hold the same doctrines’. Carson and Craig attended the service in the Ulster Hall and afterwards made their way to City Hall. Here a circular table draped with a Union flag had been set up in the main entrance foyer.

“The large majority of us here today look back to a Scottish ancestry”

Rev Henry Montgomery - Presbyterian Moderator

Shortly after noon, flanked by leading Unionists, many of them prominent Belfast citizens, Carson was the first to sign the Covenant, an image that has become one of the most iconic of the day. He was followed by Lord Londonderry and his son Lord Castlereagh and by the leaders of the Protestant churches. Modestly, Craig let others go before him and his is not one of the signatures on the first page.

Carson was the first of some 35,000 men to sign the Covenant in City Hall that day. Positioned along the corridors in the building were enough desks, pens, ink and forms for 540 men to have signed simultaneously. Photographs of the day show huge crowds massed around City Hall in Donegall Square and in the streets leading off it. City Hall remained open until 11 pm and afterwards the signed forms were taken to the Old Town Hall, the headquarters of the Unionist campaign.

While the men of Belfast made their way to the City Hall, the women signed the Declaration at a number of venues around the city. During the service at Westbourne Presbyterian Church, ‘an earnest appeal was made to the women present to sign the Women’s Declaration, with the result that at the close of the service, over 1,300 women appended their signatures to the document’.

Covenant Day Belfast, Scene Outside City Hall

The Aftermath

In the two weeks after Ulster Day there were further opportunities to sign the Covenant and Declaration at almost 100 locations across Belfast. Among the venues where men unable to take part in Ulster Day were able to sign the Covenant was the Old Town Hall which was open from 9 am to 8 pm daily until 14 October (except Sunday). On 4 October it was reckoned that another 1,300 men had signed on that day alone. By the end of that fortnight around 130,000 men and women had signed the Covenant and Declaration in Belfast.

Those who signed represented the full spectrum of Unionist society from the aristocrats and business magnates, to the mill workers and shipyard labourers. Even the Belfast rabbi’s daughter, Jennie Rosenzweig, signed the Declaration. Some signed in beautiful handwriting, while others simply made their mark. Every signatory was offered a souvenir parchment containing the words of the Covenant of Declaration. Many of the descendents of these men and women still proudly display these mementos.

In Ulster as a whole, the Covenant was signed by 218,206 men and the Declaration by 228,991 women. In addition another 19,162 men and 5,055 women born in Ulster, but living elsewhere, signed at various locations throughout Ireland and Great Britain and also in the United States, Canada, Australia and South Africa.

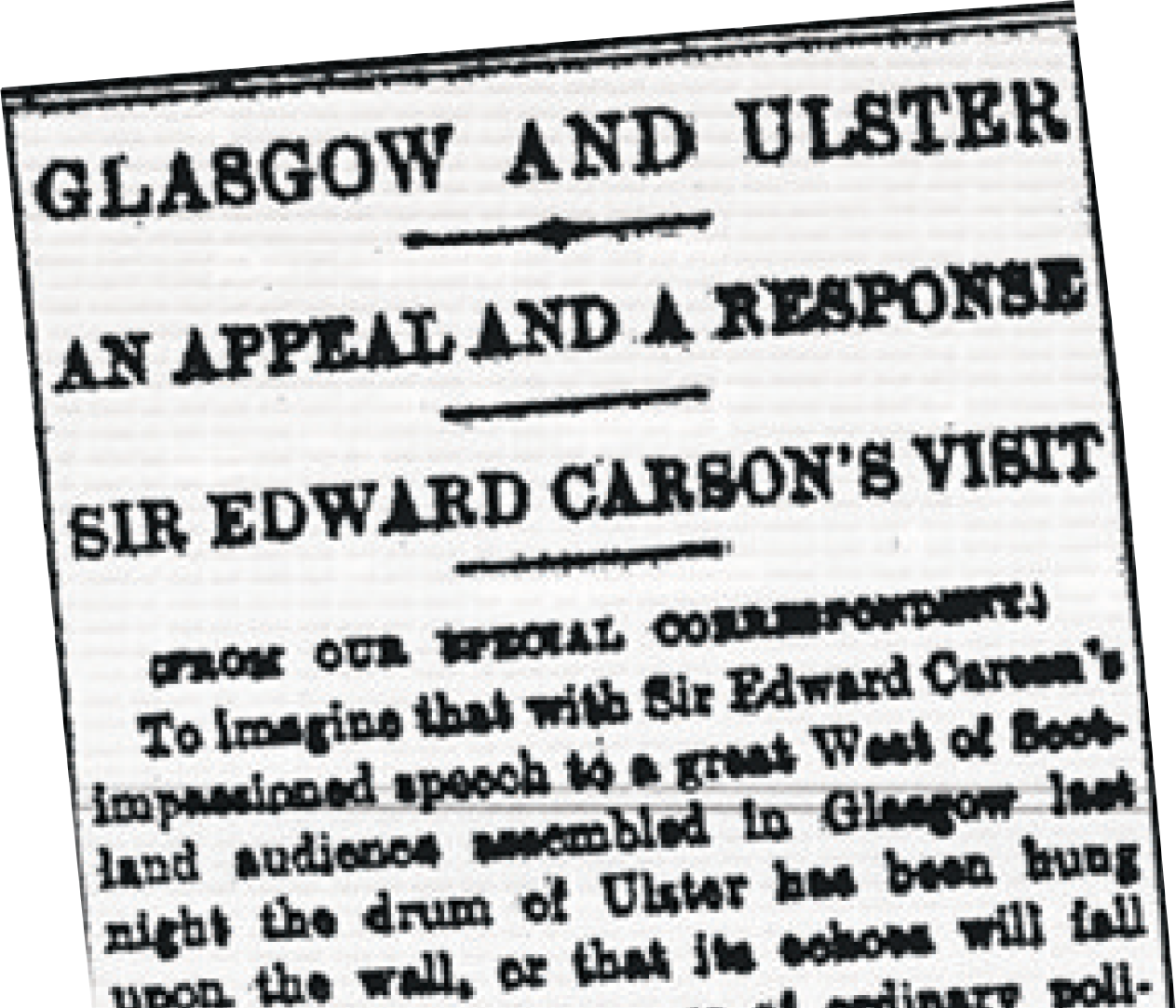

Some 17,000 people signed in Scotland, including the iconic Kirkyard of Greyfriars in Edinburgh. Two days after Ulster Day Carson spoke in Glasgow in front of a huge crowd and declared ‘Our people in Ulster are your people’. Six Belfast men signed on board HMS Monmouth which was then at Nanking in China, while double that number from Belfast signed on board the Canadian Pacific Liner SS Lake Champlain which was carrying emigrants to Canada.

The huge public support among the Unionists of Ulster for the Covenant did little to dissuade the government from continuing with its policy of Home Rule. Realising this, Unionists began to take ever more radical steps and in January 1913 the Ulster Volunteer Force was formed with membership open to those aged between 17 and 65 who had signed the Covenant.

One of the founders of the UVF, Fred Crawford (right), had himself played a prominent role in organising Ulster Day. Proud of his Scottish heritage, he claimed to have signed the Ulster Covenant in his own blood in imitation of an ancestor who had done so on Scotland’s National Covenant in 1638.

"I belong to this race and claim it with pride. One of my ancestors, the Rev Thomas Crawford, came from Kilbirnie in Scotland"

Fred Crawford

Fred Crawford

Appeal and Response

The beginnings of modern Belfast can be traced to the early 1600s when, under the direction of Sir Arthur Chichester, an urban settlement began to emerge. In the course of the seventeenth century it became largely Scottish in character and strong trading links were established with Scotland. By the middle of the 1600s Belfast had overtaken Carrickfergus as the most important town in east Ulster.

Belfast’s growth continued in the 1700s, though steadily rather than spectacularly. One historian has written: ‘In the eighteenth century Belfast was a small, predominantly Presbyterian town, not unlike one of the neat burghs of the Scottish lowlands’.

The Scottish character of the town was obvious to newcomers. For example, when a new Surveyor of Excise was appointed to Belfast in 1780 he observed that ‘the common people speak broad Scotch, and the better sort differ vastly from us, both in accent and language’. A French visitor in 1797 noted: ‘Belfast has almost entirely the look of a Scotch town, and the character of the inhabitants has considerable resemblance to that of the people of Glasgow.’

As Belfast became increasingly industrialised in the nineteenth century so its commercial links with Glasgow and the Clyde became even stronger. When, in 1886, the Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Party, William Gladstone introduced an Irish Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons, it sent shockwaves through Belfast’s business community. One of the strongest arguments that they put forward against Home Rule was that it would be disastrous for the trade and commerce that her prosperity depended on.

“In making good the common history and civil and religious aspirations of the peoples of Scotland and Ulster Sir Edward Carson had a congenial task ... the progress of Ulster’s capital city has emulated the municipal enterprise of Glasgow itself, and between which so many mutual interests subsist ...”

Glasgow Herald 2 October 1912

Craig, Sinclair & Carson

The introduction of the Home Rule Bill in 1886 split the Liberal Party and the Bill was defeated. In Ulster, the Presbyterians, who were traditionally Liberal, became Liberal Unionists and found common cause with the Anglican gentry with whom they had often disagreed, laying the foundations for modern Unionism. Gladstone tried again in 1892–3; this time the Bill was passed by the Commons but was defeated by the Lords.

In 1910, a new Liberal government came to power under H.H. Asquith, but it was dependent on the votes of Irish Nationalists, who demanded a third Home Rule Bill as the price for their support. As a result of the 1911 Parliament Act, the Lords could only delay any legislation passed by the House of Commons and the passage of the Third Home Rule Bill seemed inevitable. Unionist opposition to Home Rule was mobilised like never before.

By this time the leadership of Unionism had shifted decisively towards the self-made commercial and professional classes of Belfast and away from the landed gentry. Aristocrats like the Duke of Abercorn and Marquess of Londonderry remained important figureheads, but those who now ran Unionism had honed their leadership skills in business and, quite often, the army. Exemplifying this new breed of leader was James Craig. A man with great organisational ability, he was a director of the Dunville distillery, had served in the Boer War, and had been the MP for East Down since 1906.

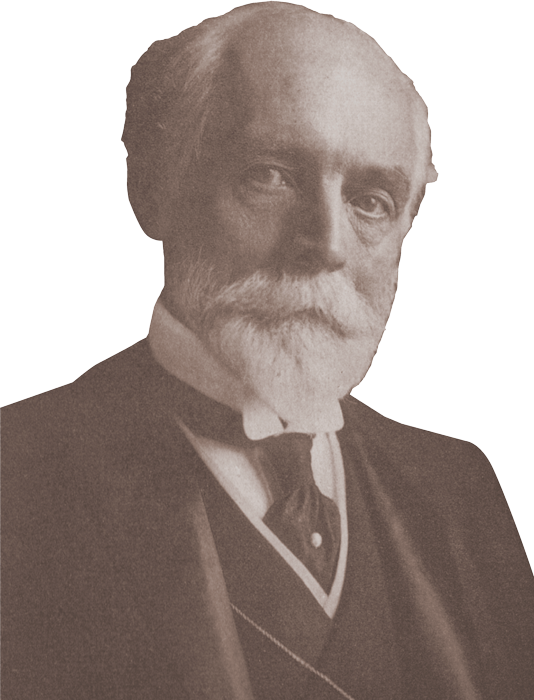

Another key figure in the Unionist leadership is a man now largely forgotten in the public consciousness. Thomas Sinclair was born in Belfast in 1838 and was an outstanding student at RBAI and Queen's. A leading figure in Belfast’s business community, he was a generous philanthropist and one of the most prominent lay members of the Presbyterian Church. A well-respected member of the Liberal Party, he declined electoral office, but played a key role as an organiser and thinker. After the party split, he was a leader of the Liberal Unionists and was instrumental in bringing Presbyterians to prominence within Unionism. He also organised the Great Unionist Convention of 1892. He set forth very clearly the position of Unionism in his essay for the 1912 publication Against Home Rule. More so than perhaps any of his contemporaries, Sinclair was conscious of his Ulster-Scots heritage.

While Craig and Sinclair brought organisational flair and intellectual force to the movement, Unionism's greatest asset was to have a charismatic leader who held an unrivalled place in the hearts and minds of the people. Sir Edward Carson was not from Ulster, though like Craig and Sinclair, he was of Scottish ancestry. A brilliant lawyer and MP for Trinity College Dublin, he had been leader of the Irish Unionist MPs at Westminster since February 1910 and in June 1911 he accepted the leadership of Unionism. An inspirational figure, he brought real gravitas to the role.

Left: Craig, Middle: Sinclair, Right: Carson