The Plantation of Ulster (1610–1630)

The Story of The Scots

In the early seventeenth century 20–30,000 Scots crossed the North Channel into Ireland. Together they formed part of one of the most significant movements of people in these islands.

Many came to the settlements in north-east County Down encouraged by two Ayrshire Scots, Sir James Hamilton and Sir Hugh Montgomery, from 1606 onwards. Others settled in County Antrim on the lands of the MacDonnells and others.

The official Plantation that affected counties Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone was different, for here settlement was not purely the result of private endeavour, but rather was part of a government-directed scheme of colonisation.

This was Scotland's first, and ultimately most successful, project of colonisation beyond its shores.

The Plantation scheme applied to just six of Ulster’s counties – Armagh, Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone. However, there had been an often-forgotten, earlier, migration from Scotland into the west of Ulster. Just after Sir Hugh Montgomery began settling Scottish families in east Ulster from 1606 onwards, his younger brother George Montgomery (who had been appointed as Bishop of Derry, Clogher and Raphoe) began doing likewise in his church lands of the west of Ulster, beginning around the spring of 1607 – before the Flight of the Earls from Rathmullan in Donegal which took place in September of the same year.

“(George Montgomery) was very watchfull, and settled intelligences to be given him from all the sea ports in Donegal and Fermanagh ...

the ports resorted from Scotland were Derry, Donegal, and Killybegs; to which places the most that came were from Glasgow, Air, Irwin, Greenock, and Larggs*...

masters of vessels should come to his lordship with a list of their seamen and passengers ... he was their merchant and encourager”

* Glasgow, Ayr, Irvine, Greenock and Largs

Scotland to Ulster: A century of migration

If large-scale Scottish migration to Ulster began with the Hamilton and Montgomery settlements in County Down from 1606 onwards and continued with the implementation of the Plantation scheme in 1610, it would be a mistake to think that most Scots came to Ulster in the early seventeenth century.

Significant migration from Scotland continued throughout the rest of the seventeenth century and even into the early eighteenth century reinforcing the Scottish tinge to the character of much of the province. In the 1650s migration to the north of Ireland was encouraged by low rents in the aftermath of a decade of warfare. In the 1670s the Covenanter disturbances in Scotland resulted in Scots seeking refuge in Ulster.

The aftermath of the Williamite war (1689–91) saw a fresh influx of thousands of Scots to the north of Ireland. The principal driving factor in this migration was the distress caused by harvest failures resulting in severe famine conditions in Scotland. It has been estimated that as many as 50,000 Scots crossed the North Channel in this decade alone – a far greater number than came to Ulster in the first four decades of the seventeenth century.

A tract of c.1711 noted that after 1690:

“Scottish men came over into the North with their families and effects and settled there, so that they are now at this present the greater proportion of the inhabitants.”

Though this was an exaggeration of the overall numerical position of the Scots, it was probably the case by this time that they outnumbered English settlers by two to one.

Europeans on the move

The movement of Scots to Ulster in the 1600s was just one example of Europeans on the move in the Early Modern Period. Elsewhere in this publication it has been noted that more Scots went to northern and eastern Europe in the early seventeenth century than came to Ulster.

This was also the period in which Europeans were beginning to colonise the Americas. In the same period that the Plantation of Ulster was taking place the English were establishing a colony at Jamestown in Virginia, while in 1620 the Pilgrim Fathers founded the Plymouth Colony in New England.

In the 1620s the first official attempts to create Scottish settlements in America took place, though these colonies in what became Nova Scotia proved ill-fated.

1. Scotland on the eve of The Plantation

It may surprise many people to learn that in the early seventeenth century more Scots went to Poland than came to Ulster. In fact more Scots went to Scandinavia than came to Ulster. We often think of the Scottish migration to Ulster as being of enormous significance in the population history of Scotland. There is no denying that it was, but the reality of the situation is that in the early 1600s the Scots were a people on the move and Ulster was just one of their destinations.

During the reign of James VI Scotland became a much more politically stable kingdom than it had been for some decades. The King was able to impose his authority on the nobility and gentry and to establish law and order in the notoriously unruly Borders. Scotland’s population was rising and there was a surplus of young men seeking employment or adventure – hence the numbers of Scots venturing abroad. These migrants, however, were not travelling as part of any co-ordinated colonisation scheme.

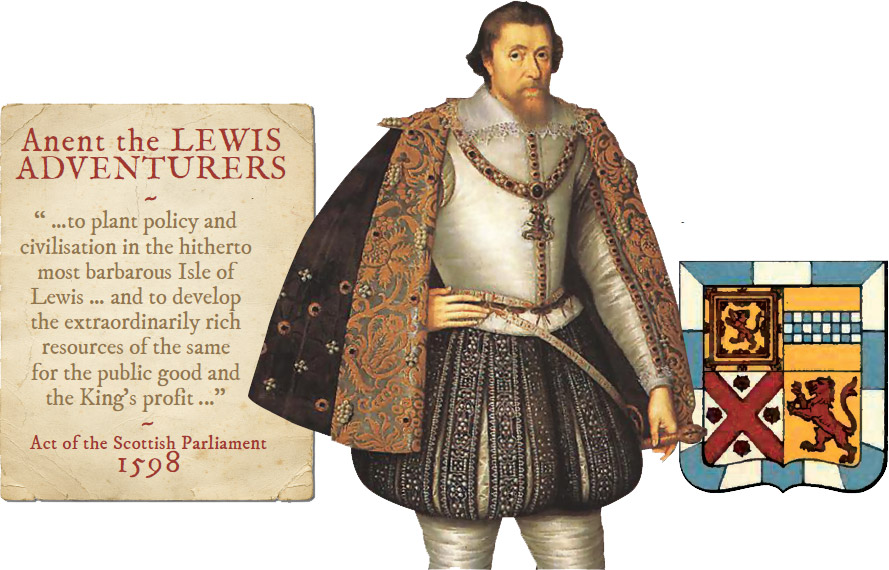

Prior to the Plantation, the Scottish crown had been involved in a number of attempts to ‘plant civility’ in the fringes of Scotland in the 1590s and early 1600s. The king hoped that by planting Lowland Scots in the Isles it would ‘reform and civilize the best inclined among them: rooting out or transporting the barbarous and stubborn sort’, though the results of these endeavours were mixed. Some of those who were later to play a part in the Plantation in Ulster were involved in these initiatives, such as Andrew Stewart, Lord Ochiltree, who would receive lands in east Tyrone.

With the succession of James VI to the throne of England, the Scots were guaranteed a key role in the official efforts to colonise Ulster. The Scots embraced the opportunities for economic and social advancement presented by the Plantation scheme with much enthusiasm at all levels of society. The scheme for the Plantation in Ulster, therefore, provided Scotland with an opportunity to embark on its first, and ultimately most successful, project of colonisation beyond its shores.

2. Scots in Pre-Plantation Ulster

The links between Scotland and Ulster date from time immemorial and for millennia people have been crossing the North Channel dividing or, from another perspective, connecting, the two. In the Middle Ages mercenary soldiers, known as galloglagh, from the Highlands and Islands of Scotland arrived in Ireland to fight for the Gaelic chieftains. In the sixteenth century, there were further influxes of mercenaries, often referred to as Redshanks, from Scotland. For example, when Turlough Luineach O’Neill, chieftain of the O’Neills, married Lady Agnes Campbell in 1569 a thousand Scottish mercenaries, probably from Argyll, arrived in the north Tyrone area. It is likely that the descendants of these comprised the ‘above three or four score Scottish families inhabiting’ at Strabane in 1598.

Very different from these Highlands and Islands Scots were the Lowland Scots who began to arrive in some numbers in counties Antrim and Down in the early seventeenth century. The large-scale Scottish settlement in County Down from 1606 onwards was promoted by two men from Ayrshire, James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery, who had acquired large estates from lands formerly owned by Con O’Neill.

The largest land grant made in Ulster in the early seventeenth century was the grant of the greater part of the four northern baronies in County Antrim – an area of well over 300,000 acres – to Randal MacDonnell in 1603. Originally from the Isles, the MacDonnells had been establishing a secure foothold in north Antrim for some time before this. Despite his background and his strong support for Catholicism, Randal MacDonnell invited Protestant Lowland Scots to settle on his lands in order to develop his massive estate.

In the west of the province there had been some penetration by Lowland Scots prior to the implementation of the Plantation scheme. One who actively encouraged Scots to settle in this region was George Montgomery, brother of Sir Hugh Montgomery, the County Down landowner, and from 1605 the bishop of Derry, Raphoe and Clogher. The chronicler of the family’s history, writing at the end of the seventeenth century, praised Bishop Montgomery for his ‘usefulness in advancing the British plantation in those three northern dioceses’. He encouraged Scots to settle on lands owned by the Church by offering them land on good terms.

3. The Scots in the Plantation Scheme

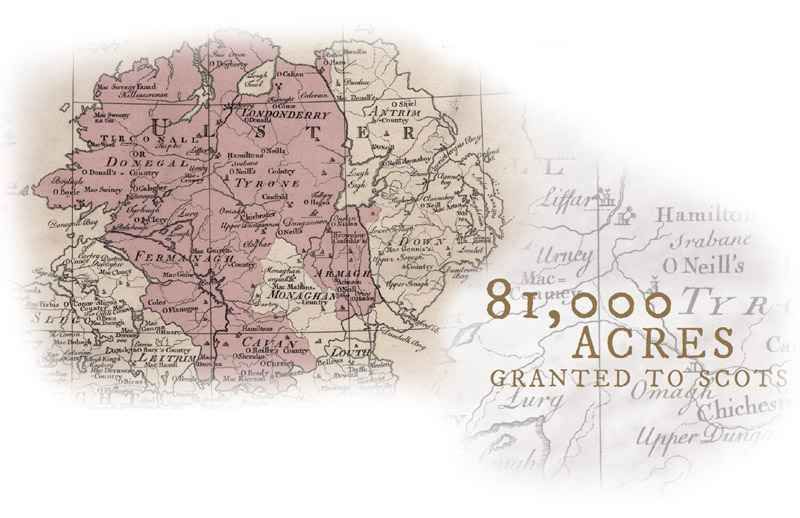

The so-called ‘escheated counties’ that formed part of the official scheme of Plantation were Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine (renamed Londonderry), Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone. The Scots were just one of several groups who received lands in these counties. In addition to their English counterparts, there were servitors (only two of whom were Scots), ‘deserving’ Irish, the Church and institutions such as Trinity College. Nine precincts were set aside for Scottish grantees: Boylagh and Bannagh, and Portlough in County Donegal; Strabane and Mountjoy in County Tyrone; Knockninny and Magheraboy in County Fermanagh; Clankee and Tullyhunco in County Cavan; and Fews in County Armagh.

In each precinct there was a chief undertaker (so called because they undertook to plant their lands), who was often related to or in some way connected to the other undertakers granted lands in the same precinct. There were originally 59 Scottish undertakers, who between them owned 70 proportions, as the individual land units were known.

Several undertakers, particularly the chief undertakers, owned two or, in one instance, three proportions, together comprising a single estate.

Much interest in acquiring plantation land had been shown by the wealthy urban middle classes, particularly in Edinburgh, but in the end the government chose, for the most part, middle ranking lairds who would have had greater experience of estate management. The chief undertakers in each proportion were all titled and many of them enjoyed close relationships with the king.

The total plantation acreage granted to Scots came to 81,000, only 500 acres less than that granted to English undertakers. The proportions allocated to the undertakers were of three sizes: small (1,000 acres), middle (1,500 acres) and great (2,000 acres). Of all the different groups of grantees, the undertakers alone were expected to colonise. For every thousand acres that he was granted an undertaker was required to introduce ten families of British origin, comprising at least twenty-four adult males.

4. The progress of Scottish Settlement

The initial progress made by the Scottish undertakers varied considerably and in some areas very little if anything was achieved in the early stages of the Plantation. Many of the undertakers found that the task they were taking on was simply beyond them. The average Scottish laird was not a wealthy man. In November 1610 the lord deputy of Ireland, Sir Arthur Chichester, made the following observation: ‘The Scottish come with greater port and better accompanied and attended, but it may be with less money in their purses’.

Some undertakers granted estates in less favourable areas found it virtually impossible to induce Scots to settle on their lands. In east Tyrone Bernard Lindsay’s proportion lay ‘towards the mountains and is extremely rough and scarcely habitable’. When Scottish settlers arrived there ‘at the first site of the barrenness thereof [they] made their instant retreat’. A few of the Scottish undertakers never visited their estates at all, while others took possession in person, but sold out soon afterwards. Others attempted to develop their lands, and a few even made some progress, but for various reasons decided not to persevere.

By 1619 more than half of the Scottish estates – 33 out of 59 – had passed out of the ownership of the original grantees. In their place came men with the energy and determination, not to mention the resources, to make the Plantation a success. For example, in Clankee, County Cavan, three Hamilton brothers, Sir James, John and William, who are more usually associated with settlements in County Down, acquired five of the six original proportions in the precinct before 1619. John Hamilton in addition acquired three proportions in the precinct of Fews in County Armagh.

The story of the Hamilton brothers highlights the fact that one of the main consequences of the ready market in Plantation land was that it allowed several individuals to build up estates considerably greater than that originally permitted under the rules of the Plantation. One who did so spectacularly was Sir William Stewart who, from relatively unremarkable beginnings, was able to build up a vast estate spread over three baronies in counties Donegal and Tyrone, constructing fortifications at Fortstewart and Ramelton in Donegal, and Newtownstewart and Aughentaine in Tyrone. In 1622 he boasted that no undertaker in County Tyrone had ‘builded and plainted better uppon theer land’.

5. Numbers of Scots in Plantation Ulster

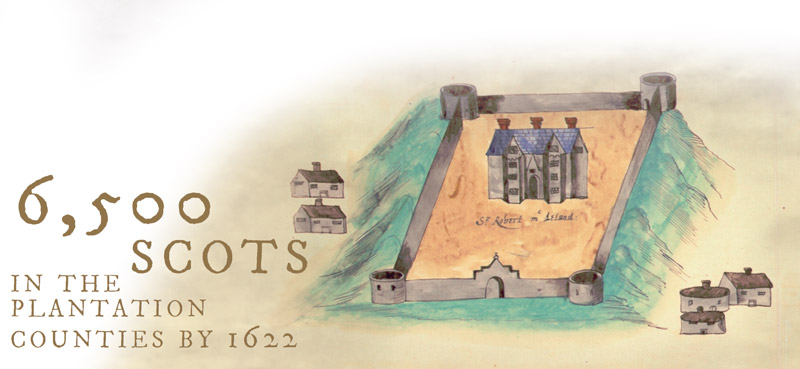

Despite inconsistencies in the progress of settlement, it has been calculated that by 1622 there were some 3,740 Scottish men in the six planted counties and a total adult Scottish population – based on there being three women for every four men – of just over 6,500. Philip Robinson’s map based on the muster rolls of c.1630 serves as the best indicator of the distribution of Scots in early seventeenth-century Ulster. From this several key areas of settlement in the escheated counties are identifiable. The most important area of settlement was the Foyle Valley straddling counties Donegal and Tyrone where between the precincts of Portlough and Strabane there were by 1619 over 1,000 Scottish men.

Other areas of significant Scottish settlement were the precincts of Mountjoy (Tyrone) and Fews (Armagh) where there were, respectively, an estimated 210 and 220 Scottish families by 1622. Scottish settlement was, however, less impressive in counties Cavan and Fermanagh. In County Cavan there were probably no more than 100 Scottish families between the two precincts allocated to Scots in 1622, in County Fermanagh there may have been around 120 Scottish families on the proportions originally granted to Scots, most of them living close to Upper and Lower Lough Erne.

What is also clear from looking at the settlement pattern of the Scots in the officially planted counties is that by the 1620s some 40% of Scottish settlers lived in areas that had not originally been allocated to Scottish undertakers. Many of these settlers lived on English-owned estates or estates that had been acquired by Scots from English. In fact nearly all British-owned estates had some Scottish tenants. This highlights the fact that there were various factors at play in determining the distribution of Scots in Plantation Ulster.

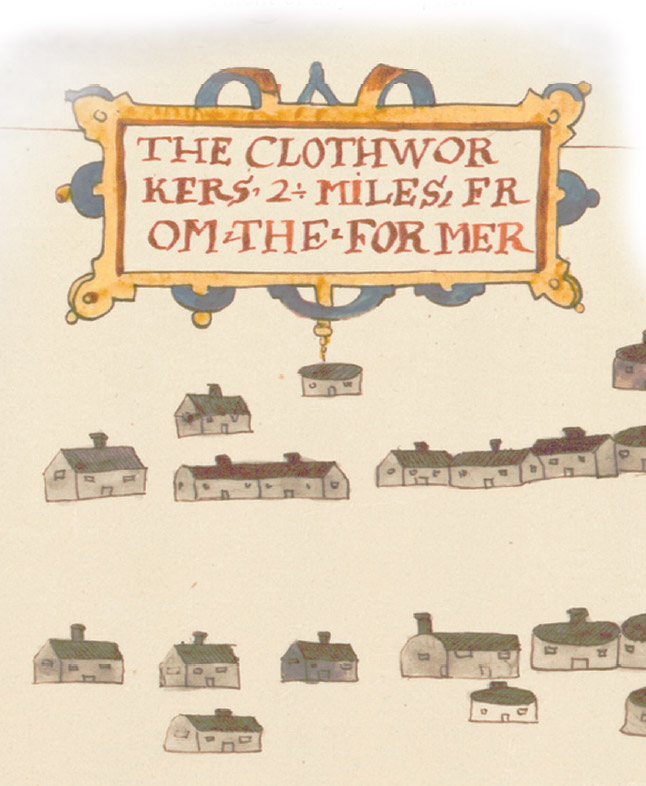

One of the areas not granted to Scottish undertakers in which Scottish settlement was heaviest was the north of County Londonderry. The influx of Scots to this area was largely due to the efforts of one man – Sir Robert McClelland from Kirkcudbright. He leased the lands allocated to two London companies – the Haberdashers and Clothworkers – and began to introduce settlers from south-west Scotland as his tenants. By 1622 there were 120 British settlers on the Haberdashers’ proportion and another 86 on that owned by the Clothworkers. These figures were higher than those for the other estates in the county and meant that northern County Londonderry now had a distinctly Scottish tinge.

6. Plantation People

‘ ... from Scotland came many and from England not a few, yet all of them generally the scum of both nations, who, for debt, or breaking and fleeing from justice, or seeking shelter, came hither ...’

The words of Andrew Stewart (d. 1671), Presbyterian minister in Donaghadee, have often been quoted to describe the early settlers to Ulster. But was this a true reflection of those who came here in Plantation times? The answer is no. The criminal element among the incomers was quite small and in actual fact the settlers from Scotland came from a wide range of backgrounds reflecting the full spectrum of Scottish society.

In the years that followed the allocation of the lands to the undertakers, hundreds of families from Scotland began to arrive in the ‘planted counties’. Their reasons for making the journey varied. Many were brought by the Scottish lords to their new estates. For example, in 1611 it was noted that Lord Ochiltree, afterwards Lord Castlestewart, had travelled to his proportions in east Tyrone ‘accompanied with 33 followers, gent[lemen]. of sort, a minister, some tenants, freeholders, and artificers’. When Sir James Hamilton acquired Plantation land in County Cavan he introduced Scottish families previously living in County Down to his new estate. When Hamilton later sold this estate these families returned to County Down.

On many of the Scottish-owned estates, there is evidence that bonds of kinship existed between the landlord and his tenants. Other settlers came independently in search of a better life. Some no doubt thought that Ulster would provide an opportunity to revive the family’s economic fortunes and recover status lost in Scotland. For example, Alexander Cairns or Kearns was an impoverished Scottish laird who left his home country to seek a better life in west Donegal. Here he prospered, acquiring lands and wealth for himself.

The majority of the Scottish settlers came from the south-west of Scotland and in particular Ayrshire, Lanarkshire, Renfrewshire, and Dumfries and Galloway. We know very little about any of them and in only a relatively small number of instances is it possible to identify the precise place in Scotland from where they originated. In the case of the lands leased by Sir Robert McClelland in north County Londonderry it is possible to show that some, if not most, of the tenants came from the Kirkcudbright area, from where Sir Robert himself originated.

There was also a strong contingent from the Borders. The latter included families such as Armstrong, Elliott and Johnston. This was an area that had been associated with lawlessness – hence the use of the word Reiver (from reive – to rob or plunder) to describe the people of this area. In the years immediately prior to the Ulster Plantation, James VI of Scotland began a concerted campaign to stamp his authority on the Borders and bring to an end the disorder for which it was infamous. Many Borders families were attracted to Fermanagh as a potential new home. Here, in an area that was remote from Britain and close to the frontier of the Plantation, they would be free from the restrictions of state authority and immune from the Scottish justice system. These families were also resilient, able to survive the upheavals of the seventeenth century, and adapt to the changed circumstances in which they found themselves.

The contribution of Highland Scots to the Plantation should not be overlooked either. In areas such as east Donegal, Plantation records include names that originated in Argyll and elsewhere in this region. Some of these Highland Scots were new arrivals, but others would have been descended from Redshanks that had settled in Ulster in the late sixteenth century. On Sir John Drummond's estate in Strabane barony it was observed in 1622 that of his tenantry 'all but four or five are Redshanks'.

7. Patterns of Settlement

The settlement pattern envisaged by the devisers of the plantation scheme was essentially one of an English model of rural settlement. The settlers were to live in towns and villages, fields were to be enclosed and English agricultural practices were to be used. For the most part, however, the reality was very different.

Though the regulations drawn up in 1610 specified that on each manor the tenants’ houses were to be built adjacent to the fortification on the estate, ‘as well for their mutual defence and strength, as for the making of villages and townships’, in reality relatively few of the Scottish-owned estates had a nucleated settlement of any description.

Even those settlements that were denoted ‘town’ or ‘village’ in the official Plantation surveys were often unimpressive clusters of six to twelve houses. For the most part the settlers lived scattered across the countryside. For example, when Captain Pynnar visited the precinct of Boylagh and Bannagh in 1618–9 he was told of the numbers of settler families present, but ‘I saw but very few of them, for they dwelt far asunder, and had no time to come unto me’.

Various factors contributed to the absence of nucleated settlements from most of the Scottish-owned estates. For one thing, the fact that the Irish townland was used as the basis of leasing militated against the creation of villages. With individual proportions much larger in reality than on paper it was simply impractical for a tenant to live in a village and travel out each day to work on his holding.

It is also true that the settlement pattern envisaged by those who devised the Plantation scheme was very different to the settlement pattern that the majority of Scottish settlers to Ulster were familiar with. Over much of Scotland, including the southwest where the majority of settlers originated, most rural dwellers lived in clusters of houses known as ‘ferme touns’. The land was largely open without hedges or dykes except around the farmsteads.

8. Towns and Villages

Despite the Scottish preference for dispersed rural settlement, more than a dozen towns and villages were founded by Scots in the officially planted counties in the 1610s and 1620s. The largest of these was Strabane which received its charter in 1613. In 1622 it was noted that there were more than one hundred houses in the town and its inhabitants were ‘very industrious and do daily beautify their town with new buildings, strong and defensible’. Strabane was in fact the third largest town in the officially planted counties after Londonderry and Coleraine.

Among the reasons why Strabane prospered was its location, serving a large hinterland in north-west Ulster, and having direct access to the sea via the River Foyle. It had a small but important merchant community, trading directly with Scotland as well as English ports such as Bristol and Chester and even France. There was a small Scottish element to the merchant community in Londonderry.

Other Scottish settlements were either inland or were relatively isolated and in an area where the natural resources were more limited. In such places it was difficult to sustain a significant resident merchant element. For example, Killybegs in southwest County Donegal was primarily a Scottish town, but was described in 1637 as ‘wild and not inhabited with any men of power or quality and frequented especially in time of fishing by Redshanks and divers of the Scotch Isles and other unruly and wild people that will do no right that is not enjoined on them by force’.

Other Scottish settlements included Lisnaskea, Stewartstown, Clancarny (Markethill) – all founded by chief undertakers – Newtowncunningham and Ramelton. Further down the scale were Ballymagorry, Killeshandra and Newtownstewart. In general these settlements were populated by different tradesmen providing services to the immediate settler community.

In the absence of maps or plans, the layout of these towns and villages is almost impossible to determine. Some efforts at planning can be detected. For example, at Ramelton, Sir William Stewart had built a paved street between his castle and the church. A street also ran directly between the castle and church in Strabane, though in this case it was not the main street of the town. By 1622 the settlement at Donboy on John Cunningham’s lands in Portlough comprised 40 thatched houses and cabins with a ‘stone cawsey in the middle’.

9. The management of Scottish Estates

If a grantee of Plantation land was going to benefit financially from his undertaking he would have to manage his estate effectively to derive an income from it. He was not free to choose how to do this as he pleased but was expected to follow specific guidelines. Under the terms of their land grants, the undertakers were required to divide up their estates among tenants in a certain way. Furthermore, tenants were to be issued with written deeds that gave them security of tenure.

Relatively few of the undertakers fulfilled these conditions precisely. Some did not have enough British tenants to lease farms to, while others did not make out proper written leases to their tenants creating uncertainty among them. However, a number of the Scottish landlords did take care to ensure that their tenants were given proper leases for their holdings.

Agriculture was central to the rural economy. Crops – usually barley, oats and wheat – were grown and harvested and cattle and a few sheep were reared. The authorities were anxious that English agricultural practices were followed, hence the comment ‘I find here good tillage after the English manner’ made by Captain Pynnar about William Baillie’s estate in County Cavan. However, Pynnar lamented the lack of endeavour by the English and Irish to practice good husbandry and pursue agriculture seriously. He wrote: ‘were it not for the Scottish Tenants, which do plough in many places of the Country, those Parts may starve’.

Scottish landlords also played an important role in introducing livestock to their estates. These were, in the main, cattle and horses, the latter being important for ploughing. On the proportion of Sir James Cunningham in east Donegal there were by 1611 some 44 head of cattle, ‘one plow of garrons and some tillage last harvest’. Lord Ochiltree brought 50 cows and 60 young heifers out of Scotland which were landed at Island Magee in County Antrim and then driven overland to east Tyrone.

Also part of the infrastructure of the estate were buildings such as mills, forges and barns. Most of the undertakers built mills on their estates. These were mainly corn mills though there were also a number of tuck mills for ‘fulling’ woollen cloth. Uniquely, the Earl of Abercorn had built a ‘great brew house’ in Strabane by 1611.

‘were it not for the Scottish Tenants, which do plough in many places of the Country, those Parts may starve’. Captain Nicholas PYNNAR, 1619

10. Scots and The English

The English and Scottish undertakers were virtually equal partners in the Plantation scheme in terms of the acreages of the lands they received: 81,500 and 81,000, respectively. Together they were intended to be part of one ‘British Plantation’ and it was hoped that ‘some course may be taken that the English and Scottish may be placed both near and woven one with another’. It was anticipated that markets and assizes would be places where English and Scots would meet and interact.

For the most part, however, the English and Scottish settlers lived largely separate lives. On many of the Scottish-owned estates, especially in the Foyle Valley, English tenants were virtually unknown. The major exception to this was in County Cavan where there was a much closer ratio of English to Scots on the Scottish-owned estates. On Sir James Craig’s estate there were actually more English settlers than Scots. On the other hand, many Scots lived and farmed successfully on English-owned estates, in some instances making up a majority of the British tenants. Though undoubtedly there were personal animosities between Englishmen and Scots, on the whole the relationships between the two groups were reasonably good.

Disputes did of course arise. In 1614 Lord Audley, an undertaker in the barony of Omagh, claimed that some Scottish settlers had tried to take his life following an accusation that he had spoken disparagingly of the Scottish nation. Audley denied this and added that not only did he have English tenants on his estate, ‘I have so many more of Scotchmen besides which sheweth no malice, but my love and good opinion towards that nation and we all agree very well’.

In another instance from 1622 the English settlers on Sir Archibald Acheson’s estate in County Cavan complained of being badly treated by the landlord’s agent. However, these incidents do not appear to have been commonplace. It might be noted that there was a degree of intermarriage between English and Scots, especially among the landed elite. One interesting aside to the cultural and linguistic hiccups that could arise relates to the fact that in 1624 the Scots asked that an additional clerk of the Council in Dublin be appointed who could read Scottish handwriting as they were concerned that their petitions were either being misunderstood or ignored. A Scottish clerk was duly appointed.

11. Scots and The Irish

The fate of the Irish in the Plantation is one of the most controversial aspects of the scheme. Under the rules of the Plantation the undertakers were forbidden to lease land to Irish tenants. As with so much else about the Plantation, the theory was very different from the practice. In the earliest stages of the Plantation, it was claimed that the Scots were leasing farms to Irish tenants and promising them that they would not be dispossessed.

The shortage of British tenants and the willingness of the Irish to pay higher rents in order to hold on to their lands meant that significant numbers of Irish continued to live on most of the undertakers’ proportions. On Sir John Hume’s estate in County Fermanagh the settlers actually complained in 1622 that they were in danger of being outbid for their farms by the Irish.

In the earliest stages of the Plantation we also find that there was a degree of co-operation in between native and newcomer. In 1611 the ‘diseased’ George Crawford, Lord Lefnoreis, was unable to develop his proportion in east Tyrone in person and so employed an Irish agent, Robert O’Rorke, to act on his behalf. Another native Irishman, Patrick Groome O’Devin played a much more significant role in shaping his own locality in Strabane barony during these formative years, leasing an entire Plantation estate from its owner in 1615. O’Devin was one of a number of men who, once the top layer of the old Gaelic order had been removed, were able to rise to prominence in the new dispensation.

Undoubtedly there was considerable Irish resentment against the settlers and anger at the consequent dislocation to their Gaelic way of life. Although many Irishmen did receive lands in the Plantation, these were often far from where they had lived prior to the Plantation. One Gaelic poet described the newcomers as ‘a conceited and impure swarm ... an excommunicated rabble – Saxons are there and Scotsmen’. It has even been said that the Irish hated the Scots even more than the English, though some Irish saw the Scots as potential allies against the English.

Nonetheless by the 1620s local accommodations had been reached between the Scots and the Irish in most areas. The government also recognised that it could not force the undertakers to give up their Irish tenants and in 1628 an agreement was reached by which the British landlords were allowed to lease up to one quarter of their lands to native Irish tenants.

12. Scottish Ministers in Plantation Ulster

An important component of the movement of Scots into Ulster in the early seventeenth century was the migration of Protestant ministers. Dozens of them moved to the officially planted counties in the years after the inauguration of the Plantation scheme. Some were bishops, such as George Montgomery of Derry, Raphoe and Clogher, and Andrew Knox of Raphoe, but most were clergymen serving in parishes. For the most part the Reformation made little impact on the native population, and these clergymen largely ministered to the settler community.

Some of the bishops and ministers were important agents of change, encouraging settlement in their dioceses. For example, in 1632 Andrew Knox, bishop of Raphoe, claimed to have introduced 300 British families to his bishopric lands, the majority of which were almost certainly Scottish. James Spottiswood, bishop of Clogher, actively tried to develop Clogher as a town, acquiring a patent for a weekly market and encouraging tradesmen to settle there.

It was also possible for individual clergymen of ambition to use this period of rapid social mobility to make the most of opportunities for advancement. For instance, Humphrey Galbraith, archdeacon of Clogher, acquired a landholding of his own in counties Donegal and Tyrone. Another Scottish minister who was even more successful in this regard was James Heygate, rector of Derryvullan. He made Clones in County Monaghan his home and here he was responsible for building a new church. Taking advantage of an English undertaker’s desire to disengage from the Plantation scheme, he acquired an estate in the precinct of Clankelly in County Fermanagh. Heygate was later to be consecrated bishop of Kilfenora, a small diocese in County Clare.

Presbyterianism does not appear to have made the same impact in the west of the province as it did in the east in the early seventeenth century, and there were not the same religious controversies in the officially planted counties as there were in Antrim and Down. While most of the settlers were Protestant, a few of the Scottish settlers were Catholic. In the Strabane area, several of the Hamilton landlords and some of their tenants were Catholics, while we also know that the Laird of Forsyth moved to County Cavan to escape persecution in Scotland on account of his Catholicism.