Who are the Ulster-Scots?

The Scots came to America direct from Scotland. They differ from the others in that they did not spend any time in Ulster. They came to America from different departure points, often in different migrant waves, and settled in different areas of colonial America. For example, many Scots settled in the Chesapeake area of Virginia, whilst the Scots-Irish generally helped to open up the western frontier in places like Pennsylvania, along the Shenandoah Valley, Virginia, and the Carolinas.

Scots-Irish, Scotch-Irish and Ulster-Scots – basically, these are variant names for the same people. All three terms relate to people who left Scotland, many in the seventeenth century; settled as part of various, successive waves of plantation in Ulster – the northernmost province of Ireland; stayed maybe one, two or several generations; and then moved on to North America.

From the first decades of the eighteenth century, the Scots-Irish started to emigrate to the Americas in ever increasing numbers. The migrant flow became stronger as settlers from Ulster took advantage of the opportunities in the burgeoning colonies. Having moved once already and broken the link with their ancestral home in Scotland, it was quite practical to move again to where a better future beckoned.

Although the terms, historically, have been used interchangeably in the Americas, more commonly these immigrants are referred to as Scots-Irish and Scotch-Irish in North America. Despite the assertion that Scotch applies only to whisky (see panel far right) and not to the people of Scotland, many Scotch-Irish in America are fiercely proud of this title and defend its use unfailingly, citing evidence from the period to substantiate their claim. The term Ulster-Scots, although also used in colonial America, is more commonly applied in the British Isles to refer to the people who moved from Scotland to Ulster, many of whom then, some time later, moved again to America.

For more information about Ulster-Scots history and culture, go to:

So you think you are Scottish?

You could be doubly blessed – having Scottish and Scots-Irish roots!

The large numbers of Ulster-Scots people moving from Ulster to the New World in the colonial period lends weight to the viewpoint that people of ‘Scottish’ ancestry, in many instances, will have a strongly Irish, or more specifically Ulster, dimension to their ancestry. Thus it may be the case that for many Americans today, their ancestral line is not so much purely Scottish as Ulster-Scots. And what a bonus that could be for the avid genealogist!

Although migration directly from Scotland to America continued through the period, given the scale of Ulster migration to America during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the keen genealogist should perhaps look to Ulster for their emigrant ancestors, and from there back to Scotland.

Tracing Ulster ancestors is great fun – it can be one of the most rewarding pastimes for any family historian. And after the hard work researching comes the enjoyment: exploring Ulster itself – the people, the scenery, the history. In visiting Northern Ireland, researchers are guaranteed one of life’s rich experiences. All this and still Scotland to discover as well.

For further information about visiting Northern Ireland, go to:

www.discovernorthernireland.com

For further information about tracing Irish or Scots-Irish roots, go to:

Whiskey – the most enjoyable legacy of the Ulster plantation?

The term whisky itself distinguishes the Scottish and the Irish: in Scotland it is whisky, in Ireland, whiskey. Irish whiskey is usually distilled three times and is stored for a minimum of five years in barrels before it is called whiskey; Scotch whisky is distilled twice and is stored for a minimum of three years. Because of its triple distillation, Irish whiskey is often considered to be smoother, and can be quite potent, but then the Irish generally blend their whiskey, whilst the Scots maintain the marvellous tradition of single malts. Interestingly, one of the most satisfying legacies of the Scots settlement in Ulster for those who have savoured it is Bushmills whiskey. Bushmills, located close to the Giant’s Causeway in North Antrim, was granted the first licence to distil whiskey in the British Isles by King James I. Granted in 1608, the Bushmills licence has ensured that each time we take a sip of the uisce beatha – Gaeilge; in Scots-Gaelic, uisge beatha; or Scots (Ullans/Ulster-Scots), whisky/whiskie/whusky, we are enjoying a very real aspect of the shared heritage between Ireland and Scotland.

The Plantation in Ulster

Ulster was the last province in Ireland to be brought under the control of the English Crown. This was finally accomplished following the end of the Nine Years’ War in 1603. With the accession of James VI of Scotland to the English throne as James I in that year, the course of Irish history changed forever. Following the departure from Ireland of the two most important Gaelic chieftains and a large number of their followers in 1607, the government embarked upon a scheme of plantation whereby lands were confiscated and parcelled out, for the most part, to new landowners of English and Scottish origin known as undertakers. Six counties were to be affected in the official plantation: Armagh, Cavan, Coleraine (renamed Londonderry), Donegal, Fermanagh and Tyrone (collectively known as the ‘escheated counties’). These grantees were expected to colonise, being required to plant ten families or 24 men for every 1000 acres they were granted.

The official plantation scheme did not extend to counties Antrim, Down and Monaghan. In Antrim and Down, private plantations in the early seventeenth century resulted in the large-scale migration of English and Scottish settlers to these counties. In northeast County Down, two Scots, James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery, acquired large estates from lands formerly owned by Con O’Neill. The British – overwhelmingly Scottish – settlement on the Hamilton and Montgomery estates was heavier than in any other part of Ulster. The largest land grant made in Ulster in the early seventeenth century was the grant of the greater part of the four northern baronies in county Antrim – an area of well over 300,000 acres – to Randal MacDonnell, a Scottish Catholic, in 1603. In order to develop his massive estate, MacDonnell invited lowland Scots to settle on his lands. In 1611 it was noted that adjoining his castle at Dunluce he had founded a village, containing ‘many tenements after the fashion of the Pale, peopled for the most part with Scottishmen’. To encourage Protestant Scots to settle on a Catholic-owned estate, MacDonnell contributed to the building and repair of churches.

Sir Hugh Montgomery

By 1630 British settlement was well established in large parts of Ulster, and there were clear areas of demarcation between areas in which English and Scottish settlers predominated. Scottish settlement was heaviest in north Antrim, north-east Down, east Donegal and north-west Tyrone, while English settlers were in the majority in County Londonderry, south Antrim and north Armagh. Much of the province remained virtually unsettled, including most of north, south and west County Donegal, south County Armagh, mid County Tyrone and mid County Londonderry. The more mountainous areas, far from the main British settlements, remained almost exclusively Irish.

The Images of Irlande (John Derricke)

The Religion of the Settlers

It can be reasonably assumed that most of the settlers who came to Ulster in the early seventeenth century were Protestants, even if only nominally so. The Church of Ireland was the established or state church and was organised along episcopalian lines with a hierarchy of clergy. However, several ministers from Scotland came to Ulster in this period who dissented from this view of church government, preferring the more egalitarian presbyterian system. To begin with, such men were tolerated within the Church of Ireland and there was no distinct Presbyterian denomination at this time.

In the 1630s the government began to clamp down on the activities of ministers with Presbyterian convictions. Those ministers who were not prepared to renounce their Presbyterianism were excommunicated.

St Columb’s Cathedral, Londonderry

In 1636 some of these men, with about 140 followers, set sail in the Eagle Wing for America; they never reached their destination, as storms drove the ship back. Many other Presbyterians returned to Scotland. Here Presbyterian opposition to Charles I was also reaching boiling point. In 1638 the National Covenant was drawn up in Scotland which declared Presbyterianism the only true form of church government and bound the nation to the principles of the Reformation. Many in Ulster also signed the Covenant. In response Wentworth insisted that all Scots in Ulster over the age of 16 take an oath – the infamous ‘Black Oath’ as it became known – abjuring the Covenant. Those who refused to take the oath could be fined and imprisoned. The result was that large numbers of Scottish settlers fled to their homeland; so many left, in fact, that in some places there were not enough people to bring in the harvest.

Ramelton Church, County Donegal

Catholic settlers were not entirely unknown in early seventeenth-century Ulster. There was a small, but significant, colony of Scottish Catholics at Strabane, under the patronage of Sir George Hamilton of Greenlaw, whose father was Lord Paisley, a prominent supporter of Mary, Queen of Scots. As early as 1614 Sir George’s Catholic sympathies were a source of concern for the government, and in 1622 he was described as an ‘Archpapist and a great patron of them’; it was noted that all his servants were Catholics. In the late 1620s the Church of Ireland Bishop of Derry became particularly agitated at the large number of Scottish Catholics he believed were living at Strabane under the patronage of Sir George Hamilton and his near relations.

Newtownards Priory, County Down

The 1641 Rebellion

If the position for the Scots in Ulster was bad by the end of the 1630s, that of the native Irish landowners was little better. Few had been able to make the transition to a market economy and as a result many had ended up heavily in debt, forcing them to either sell or mortgage much, or in some cases all, of their lands. Several of them conspired to rise up in rebellion against the government. On the evening of 22 October 1641 the rebellion began in Ulster, plunging the province and soon the entire island of Ireland into chaos. Under the leadership of the native Irish gentry, most notably Sir Phelim O’Neill (below), castles and towns over much of Ulster were seized by the rebels. Initially bloodshed was limited, with a number of the rebel leaders insisting that the Scottish should not be interfered with. Soon, however, the rebel leaders lost control of the peasantry and indiscriminate massacres of settlers began.

Sir Phelim O’Neill

The numbers killed in the rebellion have been a source of contention ever since the autumn of 1641. At the time, wildly exaggerated estimates – often considerably more than the entire British population in Ulster at the time – were circulated, mainly in the English press to drum up support for crushing the rebellion. Nonetheless, thousands of settlers did die in the rebellion, at least as many from exposure and disease as from murder. Those who had the means of doing so fled to Dublin or across the Irish Sea to England and Scotland. Others sought refuge with the towns that had not been captured.

In north-west Ulster resistance to the rebels was organised by the Stewart brothers, Sir William and Sir Robert, who recruited an army from among the settlers known as the Laganeers, one of the most efficient fighting machines of the war. Additional support for the settlers came in the form of a Scottish army, under the command of Major-General Robert Munro, which landed at Carrickfergus in April 1642. The conflict continued for the rest of the 1640s, and it was not until Cromwell arrived in Ireland in August 1649 that the island began to be brought under control. In Ulster most of the Scots supported the claims of Prince Charles, son of the recently beheaded king. Derry was briefly besieged by the Scots and in December 1649 an army of Scottish settlers was decisively defeated by a Cromwellian force at Lisburn.

The 1641 Rebellion

The Cromwellian and Restoration Periods

During the 1650s the remaining Gaelic landownership in Ulster was almost wiped out. Large swathes of land were confiscated from the Irish gentry as a punishment for their rebellion and granted to British settlers. For a time Scottish landowners in Ulster were also in a difficult situation, with the threat of confiscation also hanging over them for their support of the royalist cause. Eventually, however, their possessions were secured on payment of heavy fines. Cromwell died in 1658 and in 1660 the monarchy was restored. The new king, Charles II, was faced with the difficulty of having to find land for those Catholics who had remained loyal to the Crown during the previous twenty years. Several Scottish Catholics, the Marquess of Antrim and the Hamiltons in Strabane barony, County Tyrone, were restored to the estates they had held prior to 1641. Apart from this there were relatively few changes to the land settlement laid down by Cromwell.

Migration to the north of Ireland in the 1650s was encouraged by low rents in the aftermath of a decade of warfare. In the 1670s migration was encouraged by the Covenanter disturbances in Scotland. These fresh migrations were having a noticeable impact on local demographics. About 1670 Oliver Plunkett, Catholic archbishop of Armagh, noted that the city of Armagh had a population of approximately 3,000 persons, ‘almost all Scottish or English, with very few Irish’. This contrasted with the towns and villages in County Armagh which, according to Plunkett, were mainly inhabited by Catholic leaseholders and peasants. In the town of Dungannon, Plunkett believed that of 1,000 families barely twenty were not English or Scottish. A description of County Donegal from April 1683 noted that it was ‘plentifully planted with Protestant inhabitants, especially with great numbers out of Scotland’.

By the second half of the seventeenth century the Presbyterian Church had emerged as a distinct denomination and there were clear lines of demarcation between it and the Church of Ireland. On the whole Scottish settlers were Presbyterian, while English settlers were Anglican, although there were numerous exceptions to this rule. In County Antrim Presbyterians formed an absolute majority. In 1673 Plunkett commented that in the dioceses of Connor and Down (comprising almost all of County Antrim and north and east County Down), the Presbyterians – ‘whose belief is an aborted form of Protestantism’ – were more numerous than Catholics and Anglicans put together. On another occasion he wrote that ‘one could travel twenty-five miles in my area without finding half a dozen Catholic or Protestant families, but all Presbyterians’. In 1683 Richard Dobbs noted that all the inhabitants of Island Magee in County Antrim were Scottish Presbyterians.

Albert Conyngham of Springhill

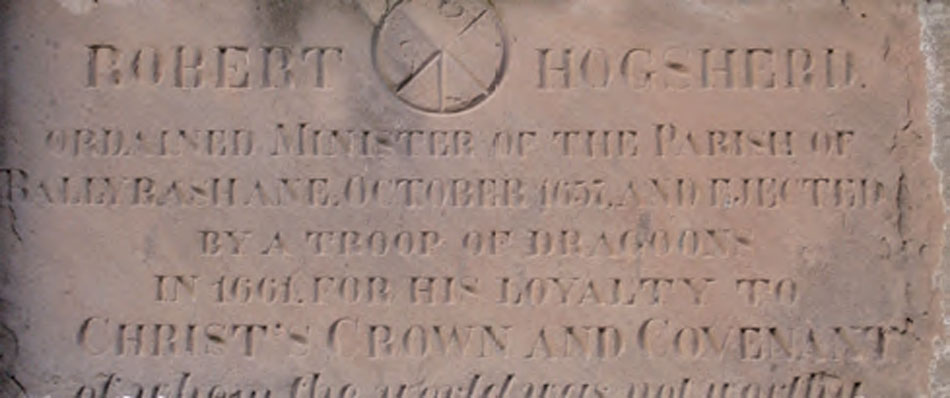

Robert Hogsherd 1661 memorial, Ballyrashane, County Antrim

The Williamite War in Ulster

The accession of James II, a Catholic, to the throne in 1685 created considerable unrest among Ulster’s Protestants. In 1688 William of Orange arrived in England and was declared king in what was known as the Glorious Revolution. James II fled to France and the following year landed in Ireland with a large French army. Protestant resistance in Ulster had already been mobilised. On 21 March 1689 the famous 105 day siege of Derry began. As many as 30,000 settlers as well as a garrison of 7,000 men were packed into the city; it was reckoned that 15,000 of them died of fever or starvation or were killed in battle. The siege was lifted in late July. Soon afterwards, a large Williamite force under the command of the Duke of Schomberg landed near Bangor, County Down, and by the autumn of 1689 James’ forces had been all but removed from Ulster. As the war moved south, with decisive battles fought at the Boyne on 1 July 1690 and Aughrim on 12 July 1691, the province began to recover from the consequences of the conflict.

The aftermath of the Williamite war saw a fresh influx of thousands of Scots in the north of Ireland, encouraged by harvest crises in their native land. About 1700 it was noted that due to a fresh wave of migration from Scotland, ‘the dissenters measure mightily in the north’. In some places there were Presbyterian ministers and congregations where previously there had been none. An anonymous Jacobite tract of c.1711 noted that after 1690 ‘Scottish men came over into the north with their families and effects and settled there, so that they are now at this present the greater proportion of the inhabitants’. Though this was an exaggeration of the overall numerical position of the Scots, it was probably the case by this time that they outnumbered English settlers by 2:1.

James Corry

The Battle of the Boyne, July 1690

The early eighteenth century

Migration to Ulster, mainly from Scotland, continued into the early eighteenth century. This was impacting in areas where British settlement had hitherto been fairly limited. In 1714 Hugh McMahon, Catholic bishop of the diocese of Clogher, wrote that ‘from the neighbouring country of Scotland Calvinists are coming over here daily in large groups of families, occupying the towns and villages, seizing the farms in the richer parts of the country and expelling the natives’. Within the diocese over which McMahon was bishop there were considerable changes brought about by the influx of British settlers. County Monaghan witnessed huge increases in the number of British inhabitants in the seventy years after 1660. The so-called census of 1659 recorded only 434 British households in County Monaghan. By 1733 there was a British presence in every parish and in some there were fairly sizeable Protestant communities.

Changes in settlement patterns were also discernible in parts of south County Armagh. In 1733 a number of landowners in the parish of Creggan invited Presbyterians to settle on their estates and as an encouragement promised to provide an income for a Presbyterian minister. As a result a significant number of families of Scottish background moved to the Tullyvallen area. In 1746 one of the local landowners, Alexander Hamilton, took out a patent for a Saturday market at Newtownhamilton and two annual fairs. The area around Newtownhamilton later became a parish in its own right, taking the name of the market town.

Sir Henry Cairnes

Eighteenth-century commentators, such as the Rev. William Henry, rector of Killesher parish in County Fermanagh, were able to differentiate between areas on the basis of the characteristics of the local inhabitants. For example, in Donegal, Henry distinguished between people of English and of Scottish descent by the way they lived and worked: ‘The English planters are easily known by the neatness of their houses and pleasant plantations of trees. The Scots, on the other hand, neglected this, but made up for it through their efforts to improve the soil.’ Others noted the difference in speech of those of Scottish descent. When travelling through County Fermanagh in the 1740s, Isaac Butler noted that in the area to the north of Enniskillen towards Lisnarrick the people all had the ‘Scotch accent’. Journeying through east County Antrim c.1760, Lord Edward Willes commented that ‘all the people of this part of the world speaks the broad lowland Scotch and have all the Scotch phrases. It will be a dispute between the two kingdoms until the end of time whether Ireland was peopled from Scotland or Scotland from Ireland’. In the latter part of the eighteenth century the Hibernian Magazine, in a description of the new market house in Newtownards, County Down, noted: ‘The language spoken here is broad Scotch hardly to be understood by strangers’.

Speaker Robert Rochfort

Presbyterianism in the eighteenth century

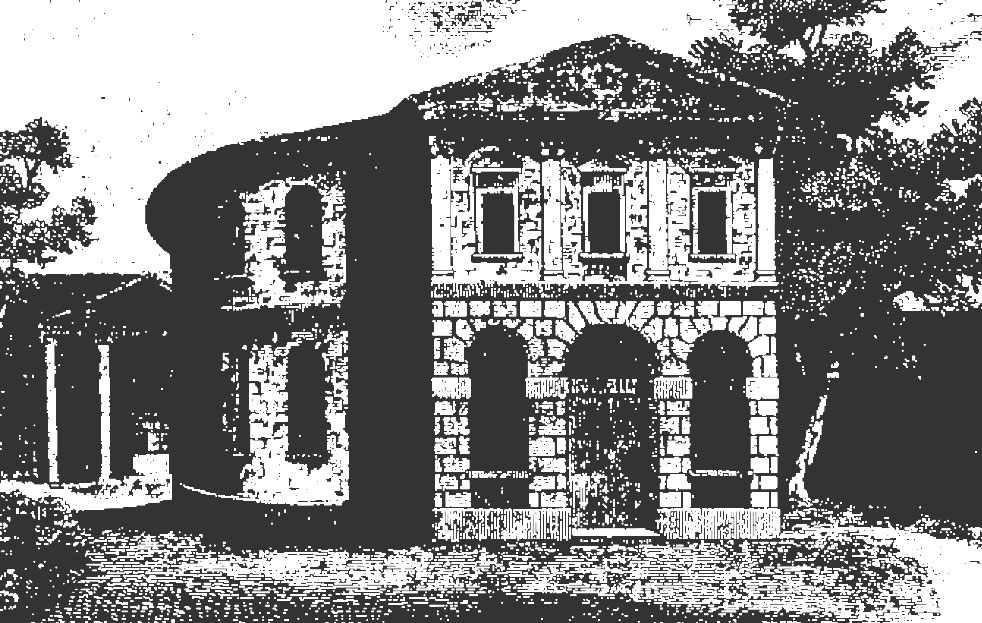

Legislation known as the Penal Laws was passed in the Irish parliament between 1695 and 1728 by an overwhelmingly Anglican landed gentry anxious to preserve their privileged position by keeping Catholics in subjection. Catholics were not the only religious denomination to face institutional discrimination in this period. Presbyterians also felt aggrieved at laws which restricted their rights and freedom in certain areas. For example, marriages conducted by a Presbyterian minister were not recognised by the state and children born of such a marriage were regarded as illegitimate. In 1704 a law was passed which required persons holding public office to produce a certificate stating that they had received communion in a Church of Ireland church. For many members of the establishment, Presbyterians were regarded as more of a threat than Catholics, especially because of their numerical superiority over Anglicans in much of Ulster.

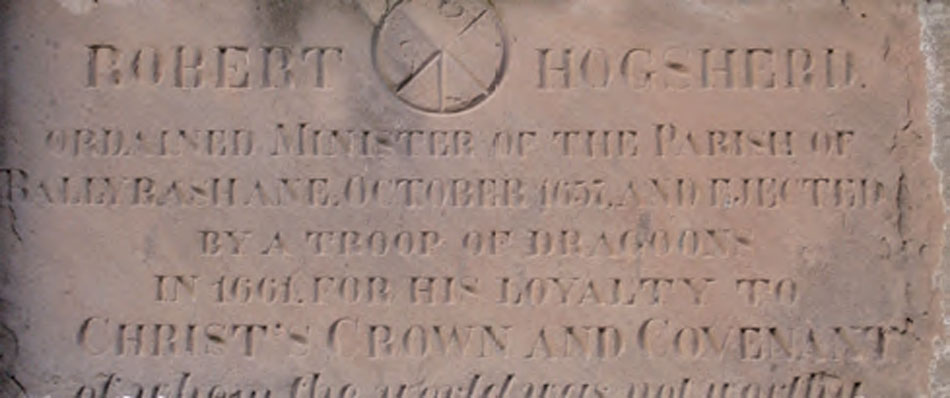

Rosemary Street Presbyterian Church, Belfast

In the early eighteenth century there occurred the first major dispute within Irish Presbyterianism. This was over the issue of subscription to the Westminster Confession of Faith. Those who denied the necessity of subscribing to the Confession were known as New Light Presbyterians. In 1725 for the sake of convenience those who took this stance were placed in the Presbytery of Antrim. Other brands of Presbyterianism originating in Scotland were established in Ulster during the course of the eighteenth century. The Seceders, as they were known because they had seceded from the Church of Scotland in 1733, soon established congregations and presbyteries in Ulster. The first Irish presbytery of the Reformed Presbyterian Church was established. The origins of this denomination went back to the National Covenant of 1638 and the Solemn League and Covenant of 1643. The Reformed Presbyterians, or Covenanters as they were also known, refused to accept that the state had any authority over the church and did not participate in parliamentary elections. Both of these denominations provided an alternative to mainstream Presbyterianism.

Test Acts Commemorative plaque, First Derry Presbyterian Church, Londonderry