Literature – an introduction

People have been writing and publishing in Ulster-Scots since the early years of the 18th century.

The preferred medium of Ulster-Scots literature has been poetry. Indeed, the earliest published texts are poems by William Starrat of Strabane (1722) and a small collection of verse, “Scotch Poems,” that appeared in The Ulster Miscellany, published in Belfast in 1753. The very end of the 18th century saw the beginning of a period of considerable creativity in Ulster-Scots writing. Much of the poetry produced at this period was written by people with links to the textile industry. These so-called “weaver poets” – people like James Orr or Hugh Porter - were deeply rooted in their localities. The work produced in this tradition, frequently outspoken, gives us fascinating insights into the political and social debates in Ulster across a good part of the 19th century. The writing often moves between English and Ulster-Scots. However, such was the antagonism of institutions like the School or the Church towards Ulster-Scots that the poets often felt they had to apologise for using what they call their “Doric rough.” This is ironic as they almost invariably produce their best material when they use the language with which they are clearly most in tune.

At the end of the 19th century we see the social origins of those who choose to write poetry in Ulster-Scots undergoing a radical shift. Whilst previously the authors had come primarily from the lower classes, the end of the century saw people like Savage-Armstrong, a contender for the post of Poet Laureate, or John Stevenson, the owner of one of the most important printing concerns in Belfast, writing in Ulster-Scots. This interest in “the vernacular” among certain sections of the intellectual and social élite reflects what was going on as regards Irish at the same period in the context of the Gaelic Revival.

The revival of interest in Ulster-Scots at the end of the 20th century ensured that this tradition has continued into the 21st century, with people like James Fenton, Charlie Gillen and Charlie Reynolds producing material in a wide variety of styles.

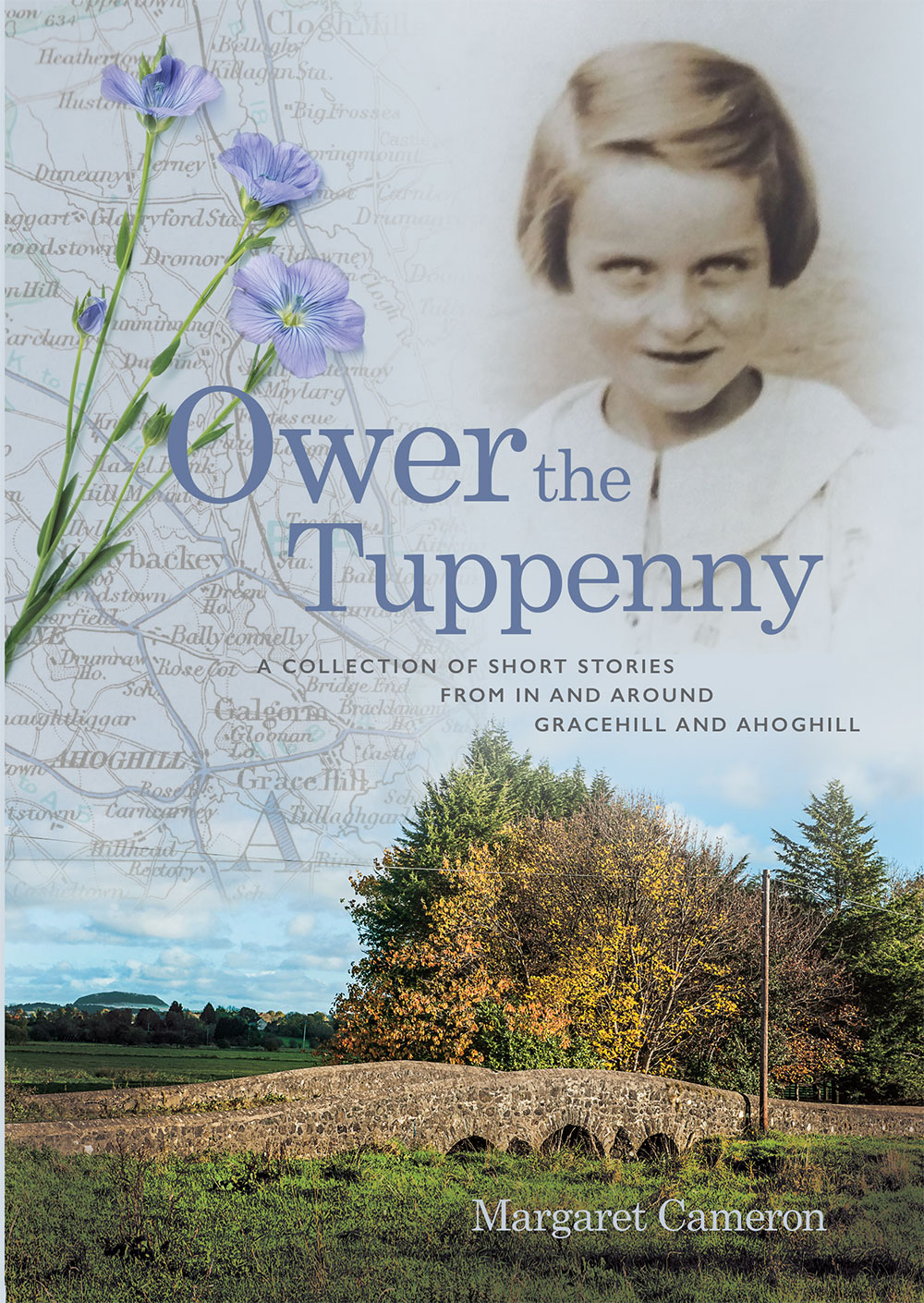

As far as prose-writing is concerned, many of the best-known novels or short stories follow the conventions of the “kailyard” style, meaning that, while the story is told in English, most of the dialogue is in Ulster-Scots. From the 1870s on, we have a number of authors like McIlroy or James, producing popular novels and stories not only for local audiences but also for people in the Ulster-Scots diaspora who wanted to tune in to familiar scenes back home. Although many of these novels are set in the rural communities of contemporary Ulster, some are historical adventures, for example, Ninety-Eight and Sixty Years After, dealing with the 1798 Rising and its aftermath in Co. Antrim, or Daft Eddie, a tale of smuggling and secret societies in the Ards Peninsula in the early 19th century. This tradition of prose writing in Ulster-Scots continues to this day.

One genre that has received less attention in Ulster-Scots is the theatre. There is, however, the example of the work around the character of Paddy M’Quillan by the newspaper editor and author, W.G. Lyttle. These sketches, entirely in Ulster-Scots, were presented on stage by the author and subsequently published in several volumes under the title, Robin’s Readings. More recently, Dan Gordon has written a number of prize-winning plays for children, the “Pat and Plain” series, that feature Ulster-Scots in the dialogue.

A final important strand of writing in Ulster-Scots is to be found in several of the newspapers serving areas with large Ulster-Scots populations. This was the case especially in Counties Antrim and Down. A publication such as The North Down Herald published several of Lyttle’s novels in serial form before they were published as complete novels. Other newspapers such as The Northern Constitution published columns in Ulster-Scots, while The Ballymena Observer published features in Ulster-Scots by a certain Bab M’Keen, the pen-name of three generations of the Weir family, the owners and editors of the paper. The fact that all this – often humorous – material was in Ulster-Scots and that the publications continued in some cases up into the mid-20th shows that the demand for such material remained strong in the local community.