Edward Bruce

The connections between Ulster and Scotland date back millennia. The story of the campaign in Ireland led by Edward Bruce, brother of King Robert I, of 1315–18 is one of the most important early examples of shared Ulster-Scottish history. This booklet focuses primarily on the Scottish background to the story and the events leading up to the invasion of Ireland, as well as the first few months of the campaign – from the landing on the east coast of County Antrim in May 1315 to the decisive battle of Connor in September of that year.

Though the story may have largely slipped from the popular consciousness, historians have long recognised that 'The Bruce campaign in Ireland was an event of far-reaching significance'. Professor Sean Duffy of Trinity College, Dublin, has written that ‘The Bruce invasion of 1315 to 1318 represents the high-watermark of Scottish involvement in Ireland in the later Middle Ages’, while the late Professor James Lydon called the campaign ‘an event of the greatest importance in Hiberno-Scottish relations and, certainly of the Middle Ages, must rank as the greatest single occasion when Scottish soldiers were involved in the affairs of Ireland.’

The story is a far from straightforward one and reflects all of the complexity of the relationships between these islands in the medieval period. For example, Robert Bruce was married to a daughter of Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, the man who would be the Scottish army’s principal opponent in the north of Ireland. At other times Scots fought Scots and Anglo-Normans battled Anglo-Normans, while Irishmen fought on both sides in the Scottish Wars of Independence. Crucial to the Scots’ early successes was the support they received from a number of the Irish leaders, to some of whom the Bruces were related.

‘Barbour’s Brus’ (1375)

The main source of information on the campaign from the Scottish perspective is the account given by ‘Master Johne Barbour’, onetime Archdeacon of Aberdeen. Though he was born shortly after the event, he was well educated, had travelled extensively and was active in the court of King Robert II. The factual content of his metrical epic narrative – The Brus, The History of Robert the Bruce King of Scots of 1375 – can be assumed to have been compiled from a mixture of living testimonies and passed down memories and is the earliest known account to have survived.

The main source of information on the campaign from the Scottish perspective is the account given by ‘Master Johne Barbour’, onetime Archdeacon of Aberdeen. Though he was born shortly after the event, he was well educated, had travelled extensively and was active in the court of King Robert II. The factual content of his metrical epic narrative – The Brus, The History of Robert the Bruce King of Scots of 1375 – can be assumed to have been compiled from a mixture of living testimonies and passed down memories and is the earliest known account to have survived.

Did William Wallace offer Edward Bruce the crown of Scotland?

Around 1297, Sir William Wallace laid siege to Perth. The account of the events which followed, as told in Blind Harry’s History of Sir William Wallace, states that Edward Bruce had just returned to Scotland, having been in Ireland. He met with Wallace, who offered him the crown of Scotland if his brother Robert Bruce did not accept it.

‘... Edward the Bruce, who had in Ireland been The year before, is now in Scotland seen, With fifty of his mother’s noble kin; Attacks Kirkcudbright, boldly enters in. And with those fifty, for he had no more, Most gallantly he vanquished nine score. To Wigtoun next he and his men are gone, The castle took, for it was left alone... Where Wallace like a true and faithful Scot, Resign’d command to Edward, and why not And promis’d that if Robert Bruce the king Did not come home in person for to reign, He should in that case certainly and soon, Have the imperial ancient Scottish crown... ...news came reeking hot, Of all the victories that Wallace got, And how he Scotland did again reduce And that he had received Edward Bruce...’

Blind Harry’s ‘Wallace’ (1470s)

The History of Sir William Wallace was written in the 1470s by ‘Henry the Minstrel’, who was popularly known as ‘Blind Harry’. It is regarded as one of the most important texts in early Scottish literature. Robert Burns said that Blind Harry’s Wallace was one of the two books which gave him most pleasure, and that it ‘poured a Scottish prejudice into my veins which will boil along there till the floodgates of life shut in eternal rest’.

The History of Sir William Wallace was written in the 1470s by ‘Henry the Minstrel’, who was popularly known as ‘Blind Harry’. It is regarded as one of the most important texts in early Scottish literature. Robert Burns said that Blind Harry’s Wallace was one of the two books which gave him most pleasure, and that it ‘poured a Scottish prejudice into my veins which will boil along there till the floodgates of life shut in eternal rest’.

William Wallace statue at the entrance of Edinburgh Castle.

Blind Harry’s ‘Wallace’ (1470s)

Late 1200s Early Links With Ireland

The historian G. W. S. Barrow remarked that ‘Ireland cannot have seemed in any sense a foreign or unfriendly country to Robert Bruce’.

Of Norman-French ancestry and with lands in northern England, the Bruces had been lords of Annandale from the early twelfth century. Around 1200, they settled at Lochmaben and built an earthen motte that still survives in the golf course.

Robert and Edward’s mother Marjorie was a descendant of Duncan, the first Earl of Carrick (the southernmost of the three districts of Ayrshire) who been granted a stretch of County Antrim from Larne to Glenarm by King John in the early 1200s. Of these lands Robert Bruce was the feudal lord. Moreover, Marjorie had O Neill ancestry and there is even a suggestion that Edward Bruce may have been fostered by an Irish family.

The most powerful Anglo-Norman lord in Ulster was Richard de Burgh, the Earl of Ulster – Robert Bruce’s father-in-law. De Burgh’s relationship with the Bruces can be traced at least as far back as 1286 when an agreement – the ‘Turnberry Band’ – was signed by which the Bruces and other Scottish nobles pledged their support to de Burgh and another Anglo-Norman lord, Thomas de Clare, in their power struggles in Ireland. It has also been argued that the ‘Turnberry Band’ formed the basis of the Bruce claim to the crown of Scotland.

Today’s Church of the Grey Friars in Dumfries, with statue of Robert Burns.

The remains of Turnberry Castle, under the lighthouse, on the Ayrshire coast within the district of Carrick. County Antrim is just across the North Channel

1296-1306: Scottish Background

The background to the Bruce campaign in Ireland was the struggle for the Scottish throne that led to first Scottish War of Independence. In the late thirteenth century there were two principal claimants to the kingship of Scotland – John Balliol and Robert Bruce, 5th Lord of Annandale (grandfather of King Robert I).

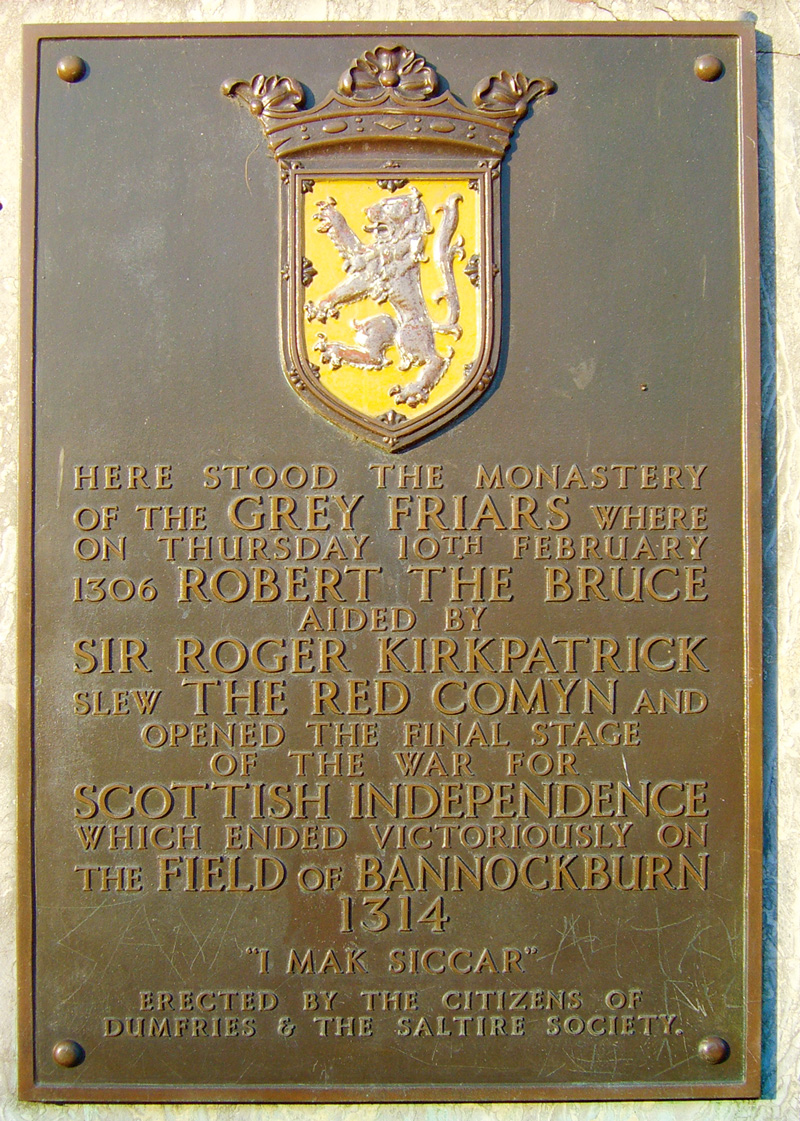

Balliol was supported by Edward I of England (‘Longshanks’) who, in return, demanded the loyalty of the Scottish lords. When Balliol rebelled against Edward in 1296, it led to a war between the Scots and the English. In 1298, following the resignation by William Wallace as Guardian, Robert Bruce (the future king) and John Comyn were appointed Guardians of Scotland. Bruce and Comyn were rivals and had an uneasy relationship which broke down completely in 1305. On 10 February 1306, Bruce met Comyn in the Church of the Grey Friars in Dumfries. A fight ensued and Comyn was killed.

Six weeks later, Robert Bruce was crowned King of Scotland by his supporters at Scone, wearing a simple gold circlet (a tableau of the event can be seen at Edinburgh Castle). Edward I responded by sending a large army to Scotland which heavily defeated the Scots at the Battle of Methven, near Perth. Bruce escaped with his life and went on the run for a number of months.

In the search for Bruce, Edward I ordered sea patrols on both sides of the North Channel to hunt for the ‘rebels lurking in Scotland, and in the Isles between Scotland and Ireland’. By September 1306 Bruce and around 200 of his followers had fled to Dunaverty Castle on the Mull of Kintyre. They sheltered here for only a few days before, with the English and their Scottish allies closing in on them, setting sail for Rathlin Island.

Today’s Church of the Grey Friars in Dumfries, with statue of Robert Burns.

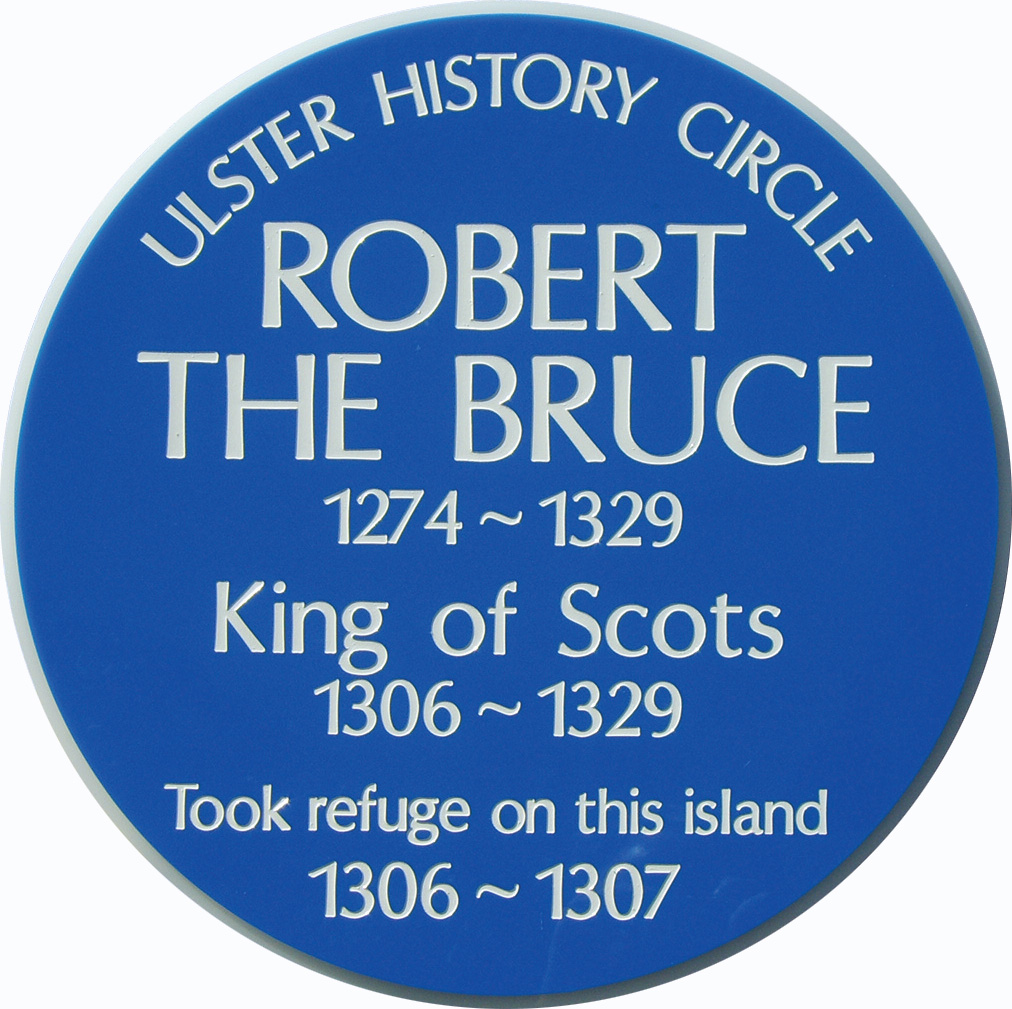

1306-1307: Rathlin Island

From autumn 1306 until February 1307, Robert Bruce and his men, probably including his brother Edward, found refuge on Rathlin, just a few miles from the north Antrim coastline. Fragmentary remains survive of ‘Bruce’s Castle’ at the north-east corner of the island. Its builders might have been members of the Anglo-Norman Bisset family and it was probably here that Bruce spent his months on Rathlin. In 2007, a blue plaque was unveiled on the island to commemorate Robert’s time there.

During the stay on Rathlin, Bruce and his men visited mainland Ireland and the Western Isles of Scotland, forging agreements and strategies with local nobles and earls, most profitably with the Macdonalds of Islay, who made their fortune by supplying Scottish soldiers (known as gallowglasses) to fight in numerous wars in Ireland. Rumours also spread that Bruce had been offered shelter in Ireland by his father-in-law, Richard de Burgh, though de Burgh denied them.

An advance party of Bruce’s men returned to Scotland, arriving at Loch Ryan around 10 February 1307. Two of the Bruce brothers, Thomas and Alexander, led 18 ships back to Scotland, but they were captured at Loch Ryan by the McDowalls of Galloway who had been loyal to Comyn. The Bruces were taken to Carlisle where they were executed. Robert returned to Scotland around the same time and began to prepare for war.

Rathlin Island, with the north Antrim coast in the foreground.

Map of Rathlin with ‘King Bruce’s Castle’ marked. Below the castle is ‘Bruce’s Cave’.

The Ulster History Circle blue plaque on the visitor centre on Rathlin Island.

1307-1314: The Road To Bannockburn

In March 1307, Robert Bruce and his men attacked an English force at Glen Trool (now in Galloway Forest Park). The encounter was brief and resulted in a Scottish victory. This battle is regarded as the beginning of the campaign for Scottish independence. Over the next seven years Robert Bruce secured a series of victories and took control of large parts of Scotland. At the Pass of Brander in 1309 Bruce defeated his sworn enemy John ‘Bacach’ McDougall – ‘John of Argyll’. This was the last major internal resistance north of the border.

During this period, his brother Edward also showed himself to be a capable military leader, leading a successful campaign in Galloway in the summer of 1308, winning victories at Craignell, Kirroughtree and the Battle of the River Dee. ‘Cairn Edward Hill’ near New Galloway marks the spot where Edward Bruce surveyed the scene of one of these victories. By the spring of 1309 he was being styled the ‘Lord of Galloway’ and his brother granted him the title ‘Earl of Carrick’ in the autumn of 1313.

In June 1313, Edward Bruce laid siege to Stirling Castle which was held for the English by Scotsman Sir Philip Mowbray. The potential loss of Stirling would have been devastating for the English. Edward Bruce entered into a pact with Mowbray that if by 24 June 1314 no English army had come to assist, Mowbray would surrender. However, this allowed time for the English to assemble an ever greater force.

A massive English army (about 3,000 horse and 16,000 foot soldiers) left Berwick for Stirling on 17 June, accompanied by many Scots who were opposed to Robert Bruce. Bruce’s army was only around 7,000 strong. The battle raged for two days, 23–24 June. The smaller, agile, Scots army routed the English, who fled southwards. The victory was Bruce’s and secured his position as ‘King of Scots’. His brother Edward had played his part in the victory, leading one of the four Scottish divisions.

Glen Trool with Bruce monument, installed in 1929.

Interpretive panel at Glen Trool, which reads ‘he first fled to Rathlin Island, then to Ulster and later to the Hebrides’. Glen Trool is part of the Robert the Bruce Trail through Dumfries and Galloway.

Anglo-Normans and O Neills: The Situation in Ireland

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Ireland was divided between areas where the Anglo-Norman lords held sway and regions that were controlled by powerful Gaelic Irish families. In Ulster the Anglo-Normans were strongest in the east of the province, especially in the coastal regions of counties Antrim and Down. The seat of Anglo-Norman power in Ulster was the town of Carrickfergus with its imposing castle that had been begun by John de Courcy in the late twelfth century.

The leading Gaelic Irish figure in Ulster was Domhnall O Neill, King of Tyrone, a distant cousin of the Bruces. For over 30 years he had been involved in a power struggle with the de Burghs. From 1310, Richard de Burgh renewed his efforts to undermine Domhnall’s authority by drawing away from him some of O Neill’s allies, and rewarding his rivals. De Burgh also extended his authority along the north Derry coast and the Inishowen peninsula, building the impressive castle of Northburgh (or Greencastle).

Finding himself increasingly threatened by de Burgh, Domhnall looked to Scotland and to Robert Bruce for assistance, encouraging the victor at Bannockburn to send an army to Ireland to fight the Anglo-Normans. Domhnall would prove to be one of the Scots’ most trusted Irish allies throughout the time they were in Ireland.

Letter to the Kings of Ireland (1315)

In early 1315, Robert wrote to ‘all the kings of Ireland’. In this famous letter he asserted his own Gaelic background, writing that ‘we and you, and our people and your people, share the same national ancestry ... common language and common custom ...’ with the aim of ‘permanently strengthening and maintaining the special friendship between us and you ...’.

In early 1315, Robert wrote to ‘all the kings of Ireland’. In this famous letter he asserted his own Gaelic background, writing that ‘we and you, and our people and your people, share the same national ancestry ... common language and common custom ...’ with the aim of ‘permanently strengthening and maintaining the special friendship between us and you ...’.

Strategically positioned at the mouth of Lough Foyle, Greencastle (also known as Northburgh), was built by Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, in 1305 at a time when he was extending his authority in the north of Ireland. It was captured by Edward Bruce in 1316.

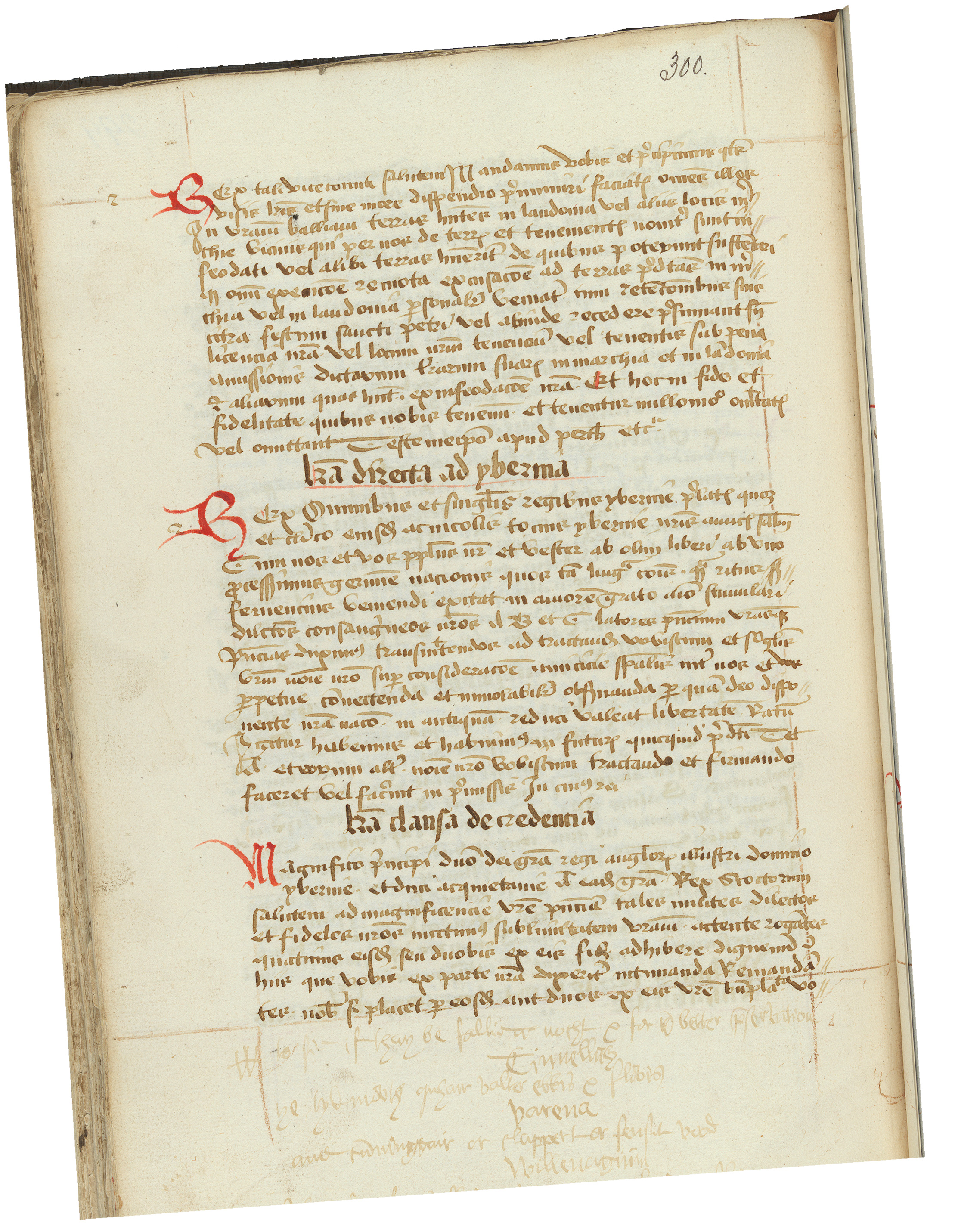

A manuscript copy of the Letter to the Kings of Ireland © Edinburgh University Library.

Edward’s Ambition Towards Invasion

Despite the crushing victory at Bannockburn, Robert Bruce’s claim to the title ‘King of Scotland’ was not recognised by Edward II of England, without which there could be no lasting peace. Bruce ruled Scotland irrespective of Edward’s acknowledgement. To the south, he initiated the ‘harrowing of the North’ by a succession of ‘scorched earth’ cross-border raids which laid waste much of the north of England that denied any new English army marching north the means to subsist.

This left the threat from the Irish Sea to be dealt with. ‘John of Argyll’ had fled south after Brander and subsequently re-entered the affray as the newly appoint admiral of the English ‘western seas’ fleet based at Dublin. From there he retook the Isle of Man from the Scots garrison, rekindling maritime warfare in the North Channel and presenting an opportunity to launch a seaborne invasion directly into Bruce’s heartland using Irish levies.

In the short term, however, the initiative still lay with Robert Bruce to open a second front by instigating his pan-Gael scheme of surrounding Edward II with rebellious subjects in his western dominions. In this plan Ireland would be the springboard for the re-taking of the Isle of Man and a link up with the Welsh rebels.

Robert de Bruce’s decision to hold a parliament in Ayr, the burgh next to his family power base of Carrick, on 26 April 1315, would appear, therefore, to have been pre-determined by the invasion plan. Edward Bruce seems to have needed little encouragement to lead the campaign in Ireland. Indeed, many see him as being the prime instigator of it and that he was motivated by dynastic ambitions of his own. As Barbour states, Edward, ‘with great joy in his heart, and with the consent of the king, gathered to him men of great valour.’

‘To be King of Ireland’

‘… Sir Edward Bruce, the Earl of Carrick, Who was bolder than a leopard, and had no desire to be at peace, Thought Scotland too small for his brother and himself; Therefore he set his purpose to be King of Ireland…’

- Book XIV, The Brus

St John’s Tower, Bruce Crescent, Ayr. A black marble plaque within the park reads ‘To commemorate the Parliament of King Robert the Bruce at this Church of St John the Baptist on 26th April 1315’.

It was this Parliament which approved Edward Bruce’s mission to Ireland. He set sail from Ayr to Antrim one month later.

Royal Burgh Ayr: Departure Port

The estuary harbour of Ayr, defended by a royal castle on the sandy spit, was then the most strategically important port on the south-west coast of Scotland. The castle overlooked the inner haven and common quay where the large European ‘cogs’ of the period could be admitted on high tides.

To the south the bleak rock-strewn Carrick coast was devoid of good anchorages or bays in which to marshal or shelter an invasion fleet as far as Loch Ryan. Landing on the beaches at Turnberry and Dunure, while fortified, offered very limited access and required a calm sea to make a landing or uplift. To the north of Ayr, entry into the estuary of the Royal Burgh of Irvine was badly restricted by a sandbar and its pool was unfortified. The headlands of Troon, Saltcoats and Ardrossan were wholly undeveloped.

In recognition of its military and civil importance Ayr had been raised to the status of Royal Burgh in 1205. The castle also sheltered the stone-built St John’s Church – the surviving tower of which was probably in existence by 1315. This charter also gave the town the rights to engage in foreign trade and hold fairs. There was a small boat-building industry which supported the offshore fisheries and occasional overseas trade ventures.

The port’s locational significance was not lost on Edward II of England who attempted to reverse the damage of Bannockburn and regain the initiative with a proposed seaborne invasion of the south-west of Scotland via this port. Fortunately for the Bruces this threat never materialised.

Ayr Esplanade, the ‘Lang Scots Mile’, scene of the departure of Edward Bruce’s fleet and 6,000 men on 26 May 1315

Bannockburn Mark II The Warriors

The army assembled for the invasion of Ireland was probably not much smaller than the Scottish army at Bannockburn and no doubt included many of the veterans of that battle. Barbour states that ‘It was a great enterprise they undertook when, as few as they were, being no more 6,000 men, they set out to attack all Ireland’. He listed the principal knights that sailed with Edward, all of whom were experienced soldiers and had close association with the Bruces.

The most significant figure was ‘Earl Thomas’ Randolph, sometimes described as a nephew of Robert Bruce. A renowned knight, he commanded the Scottish vanguard schiltron at Bannockburn. He was to the fore in the raids into northern England that reaped immense booty and ransom monies used to pay for the Ireland venture. He was created Earl of Moray, probably in early 1315, just before he sailed for Ireland. On the death of Robert in 1329, he acted as regent of Scotland for the five-year-old heir, David II.

Among the others was the ‘good’ Sir Philip Mowbray – connected to the McDowalls of Galloway – who had been the warden of Stirling Castle when it was besieged by Edward Bruce from November 1313. After Bannockburn Mowbray was reconciled to the Bruces. The ‘good’ Sir John Soulis was the son of one of the six Guardians of Scotland and joined Bruce early in his campaigns and was rewarded with lands in Dumfriesshire close to Carlisle.

The ‘doughty’ Sir James Stewart was the second son of James, High Steward and Guardian of Scotland. His father fought with Wallace at the bloody Battle of Falkirk. His elder brother Walter became the 6th High Steward of Scotland and married Robert Bruce’s eldest daughter Marjorie. Their son Robert became King Robert II – founding the Royal House of Stewart. The ‘right able and chivalrous’ Ramsay of Auchterhouse was the Sheriff of Angus. He had previously fought with William Wallace.

Warrior crests

Assembling an Armada: The Scottish Fleet

It can be safely assumed that the core of the fleet was the West Highland galleys and birlinns supplied by Robert’s two key allies – Ailean Macruari, ‘King of the Isles’, and Alexander McDonald, ‘King of Argyll’. Macruari’s domain straddled both sides of the Sea of the Hebrides including South Uist, Benbecula and Barra while McDonald’s powerbase was on Islay and the adjacent coast of Argyll. All these areas are noted for the master galley builders that King Robert had been nurturing as part of his military ambitions.

The design and construction of war galleys and birlinns was essentially that of the clinker-built Viking ‘long ship’ but with the notable addition of a steering rudder (replacing the steering oar). The larger 24-oar galleys would have been manned by 72 oarsman ‘galloglass’ warriors and, probably a further five or six acting as helmsman and sailors. The largest galleys were propelled by 40 oars requiring 120 men.

The fleet would also have been supplemented by whatever cargo-carrying cogs and herring boats were to be found in the port of Ayr. It is doubtful, however, if the fleet would have been as large as 300 boats, as stated in some sources, and may have been closer to 60–90 vessels.

Barbour states that the fleet conveying Edward Bruce and his followers went ‘straight’ to Ireland arriving on the 26 May 1315 – two days after marshalling at Ayr. The distance is approximately 60 nautical miles in a direct line, without considering the wear of wind, tide and currents, and was easily achievable in that time-scale. Loch Ryan would have provided, in all probability, the sheltered anchorage had they rested overnight.

Engraving of a medieval Highland birlinn from a tombstone in MacDufie's Chapel, Oronsay. Similar carvings of birlinns can be seen on tombstones at Kiel, Lochaline, on the Sound of Mull.

25th May 1315: The Larne Landing

According to Barbour, the Scottish fleet ‘arrived safely … without skirmish or attack, and sent their ships every one home.’ Barbour specifies the location for the landing as ‘Wolringis Fyrth’, i.e. Viking’s Forth, which has traditionally been understood as being Larne Lough. The Laud Annals refer to ‘Clandonne’ which has been interpreted as either Clondunmales (now Drumalis, Larne) or possibly Glendun further up the coast. A large fleet would have needed multiple landing locations.

The story of the arrival of the Scottish army in the Larne area was passed down through the generations and was well known in the nineteenth century. On 3 January 1893, the antiquarian F. J. Bigger spoke to the Belfast Art Society on suitable subjects for historical pictures. He said:

‘... On 25th May 1315, Lord Edward Bruce landed at Olderfleet, Larne, with a great company of Scottish nobility and 6,000 men. What a picture this would make! The Corran still remains as heretofore, and sufficient of the ancient castle of the Bissets to give an accurate idea of its original appearance; the waters of the lough covered by an animated squadron galleys, crowded with armed men, each ship displaying the flag of the clan on board, whilst that bearing the Bruce would be distinguished by a Royal banner ...’

Bigger had his wish fulfilled in 1899 when the brochure produced for the Larne Grand Fete featured on its front cover an illustration recreating the arrival of Bruce and his fleet. In 1976, a re-enactment event was held in Larne entitled ‘The Bruce Cavalcade’ when hundreds of people lined the streets.

Larne Grand Fete brochure front cover featuring an illustration recreating the arrival of Bruce and his fleet.

Larne Lough. Bruce’s fleet is likely to have landed at multiple locations along the east Antrim coastline - a stretch of land which had been granted to his ancestors by King John in the early 1200s. An estimated 2 million people every year sail by ferry between Scotland and Northern Ireland.

Late May 1315: Battle Of Mounthill

Having landed, the Scottish forces regrouped and prepared for their onward journey. Barbour records that the Scottish forces formed two divisions, one led by Edward Bruce and the other by Earl Thomas Randolph and marched toward the Anglo-Norman stronghold of Carrickfergus. They were immediately confronted by an Anglo-Norman force of 20,000 led by the Mandevilles, Bissets, Logans and Savages, whom Barbour describes as ‘the flower of Ulster’.

This battle took place in the vicinity of Mounthill, in Raloo parish near Larne. Barbour’s dramatic account gives some indication of the ferocity of the battle. The Bruce forces were victorious and headed to Carrickfergus. Curiously, this battle is not referred to in any of the Irish sources. However, the tradition of a battle at Mounthill remained strong. In 1840, James Boyle visited the area on behalf of the Ordnance Survey and recorded various stories about the battle and the Bruce connection. He wrote:

‘... Bruce’s Stones and Bruce’s Cairn, said to have been erected over a general of Edward Bruce who fell in an engagement between the Scots and English, in which the latter were defeated at Mount Hill, are still remembered by many of the inhabitants ...’

Boyle also recorded a tradition that the inhabitants of the townland of Ballygowan in the neighbouring parish of Ballynure were

‘... probably of Scottish extraction and may be the descendants of some Scots who are said to have settled in the townland of Ballygowan in this parish and in that of Raloo during the 14th century, when they came over with Lord Edward Bruce and defeated the English forces under Lord Mandeville at Mount Hill in the latter parish ...’

Larne Lough, overlooking the village of Glynn. The Battle of Mounthill took place around 3 miles from here.

Early June 1315: ‘Coronation’ at Carrickfergus

Having defeated the Anglo-Normans at Mounthill, the Scots moved on to Carrickfergus, the most important Anglo-Norman stronghold in Ulster with its imposing castle standing sentinel over Belfast Lough. Alongside the castle a town had developed which was a centre of trade and commerce. The Bruce forces seized the town of Carrickfergus – but not the castle – and established what would effectively be their base camp for the duration of the campaign.

According to Barbour, shortly after taking Carrickfergus ‘... the folk of Ulster had come entirely to his [Edward Bruce’s] peace… there came to him and made fealty some of the kings of that country, a good ten or twelve ...’. Historians have interpreted this moment as what could be described as Edward Bruce’s ‘coronation’ as King of Ireland. Professor Sean Duffy has written, ‘all the evidence suggests that Edward and his Irish allies had intended that he become king from the start of his Irish adventure and that this was in fact enacted, at or near Carrickfergus, at some stage in June 1315.’

In the Irish annals for 1315, it is recorded that ‘the Ulstermen consented to his being proclaimed King of Ireland and all the Gaels of Ireland agreed to grant him lordship and they called him King of Ireland.’

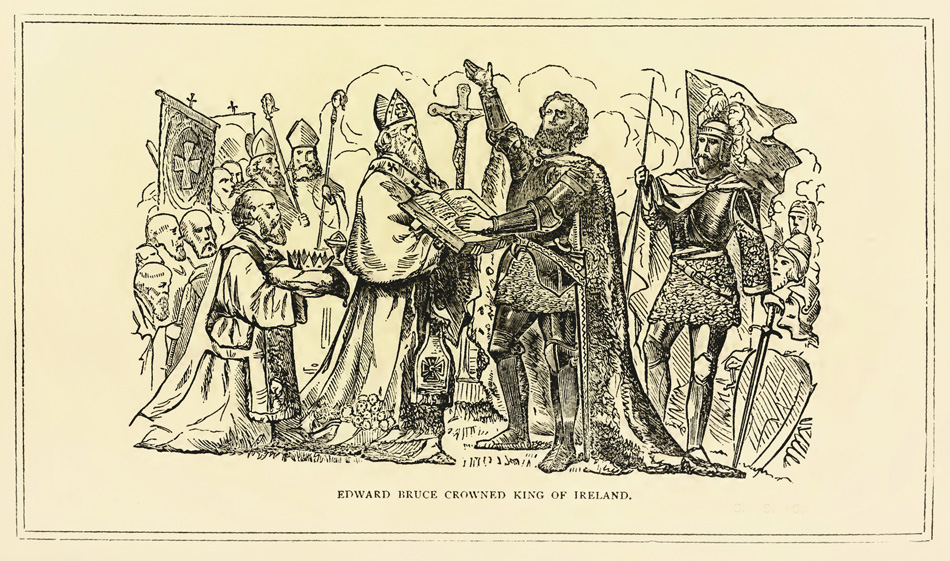

In his work 'Hints for Irish Historical Paintings', the Irish Nationalist Thomas Davis (1814-45) proposed the 'Crowning of Edward Bruce' as a subject worthy of being captured by an artist.

The Irish Leaders ‘Remonstrance’ to the Pope (1317)

One of the most important historical documents of medieval Ireland is the ‘Remonstrance’ sent by Domhnall O Neill and other Irish leaders to Pope John XXII in 1317. In this document they set out how they had sought ‘help and assistance [from] Edward de Bruyis, illustrious earl of Carrick, brother of Robert by the grace of God most illustrious king of the Scots, who is sprung from our noblest ancestors.’ According to the ‘Remonstrance’, the Irish kings had ‘unanimously established and set him up as our king and lord in our kingdom’ for they considered Bruce to be ‘pious and prudent, humble and chaste, exceedingly temperate, in all things sedate and moderate’.

One of the most important historical documents of medieval Ireland is the ‘Remonstrance’ sent by Domhnall O Neill and other Irish leaders to Pope John XXII in 1317. In this document they set out how they had sought ‘help and assistance [from] Edward de Bruyis, illustrious earl of Carrick, brother of Robert by the grace of God most illustrious king of the Scots, who is sprung from our noblest ancestors.’ According to the ‘Remonstrance’, the Irish kings had ‘unanimously established and set him up as our king and lord in our kingdom’ for they considered Bruce to be ‘pious and prudent, humble and chaste, exceedingly temperate, in all things sedate and moderate’.

Illustration of Edward Bruce being crowned, published in The Story of Ireland; a Narrative of Irish History by A.M. Sullivan (1883 edition)

Carrickfergus Castle was begun in the late 12th century by the Anglo-Normans, on the rock where Fergus, the first King of Scotland, drowned around 501. In 1315 Edward Bruce took the town and laid siege to the castle, and was reputedly crowned King of Ireland here. The castle eventually fell to the Scots in 1316. King Robert Bruce then joined Edward with a further 7,000 troops and began a campaign to try to take control of all of Ireland.

June 1315: The March South

After capturing the town of Carrickfergus, the Scottish army headed to the important town of Dundalk, one of the seats of Anglo-Norman power in Ireland. It was also a source of much-needed supplies. The Scottish force marched south, wreaking havoc on the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster. It is likely that the settlements at Dundonald, Downpatrick and Dundrum were razed at this time, while the impressive castle at Greencastle overlooking Carlingford Lough was captured.

In the Moyry Pass, one of the historic entry points into Ulster, the Scots were ambushed by 2,000 spearmen and 2,000 archers led by the Macartans and MacDuilechains who had earlier sworn loyalty to Bruce. The ambush failed. Barbour specifically mentions that the Bruce army then camped at Kilnasaggart where they prepared to attack Dundalk.

The assault on Dundalk was ferocious. It was said that the streets ran with blood as the townsfolk were slaughtered, the churches plundered and the houses burned. The Scottish army also attacked and burned the magnificent castle at Castleroche, the home of the de Verdon family, the founders of the Anglo-Norman town of Dundalk.

A huge Anglo-Norman army assembled to meet them and so, heeding the advice of Domnhall O Neill, their leading Irish ally, Bruce led his army north to Coleraine on the River Bann, possibly via Armagh, the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland, and Tullahogue, the inauguration site of the King of the O Neills. Some accounts indicate a ‘stand-off’ with the Bruce army on one side of the river, and the Anglo-Normans on the other. At a critical moment a renowned Scottish pirate, Thomas Dun, came to the aid of the Scots, using his boats to ferry Bruce’s army across the Bann.

Dundonald Motte on the outskirts of Belfast was sacked by the Bruce army on their march south.

10 September 1315: The Battle of Connor

At Connor, near Ballymena, Richard de Burgh gathered huge food stores for his own troops. Driven by hunger, Bruce’s army learned about these supplies, and travelled to within just a few miles of them. They set up camp and waited. De Burgh’s army were camped close by, and a daily patrol between the camp and the Connor food stores kept de Burgh’s men well supplied.

Choosing the right moment, a detachment of the Scots army attacked this patrol so suddenly that they had no time to retaliate. Bruce’s men took their clothing and disguised themselves as the patrol, and at dusk, they rode back toward the Anglo-Norman encampment. De Burgh’s men must have thought the patrol was returning with the day’s food. As the disguised patrol neared the de Burgh encampment, Bruce’s force launched an attack, reputedly killing 1,000 men. Victorious, the Scots rode back to their own camp to prepare for an all-out attack.

De Burgh pulled his army back into Connor that night, but early the following morning (10 September 1315) a regiment led an attack on the Bruce camp. However, the Scots had been expecting this, and as a decoy they had left their banners flying over their camp to create the impression that they were still there. De Burgh’s men were lured into the trap, and were once again attacked by the waiting Scots.

Such was the confusion that Bruce’s army entered the town of Connor, took control of the food stores and seized the corn, flour and wine and carried it to their headquarters at Carrickfergus. One of the most important battles in medieval Ulster, Bruce’s victory at Connor left him as the effective master of the northern province of Ireland.

‘A place of some importance’

The 19th-century historian George Benn observed: ‘Connor from its antiquity and ecclesiastical character – but still more from its association with the name of Edward Bruce – is, perhaps, one of the most interesting spots in the County of Antrim.’ Once the location of a cathedral, in the early 1300s it was a place of some importance. To the south of Connor is ‘Bruce's Hill’, so named from the place where Edward Bruce is said to have stood. In Barbour’s The Brus, Connor is spelled ‘Coigneris’. Older residents still pronounce it as ‘Conyer’.

Today there are two signs on the approaches to the village of Connor which include a representation of Edward Bruce.

September 1315 - October 1318: The Remainder of the Bruce Campaign

The story of Edward Bruce’s campaign in Ireland lasted for three more years and will only be briefly summarised here. Though the victory at the Battle of Connor left Edward Bruce in a seemingly impregnable position, the castle at Carrickfergus with its Anglo-Norman garrison was still holding out. At one point 60 Scots were taken hostage, eight of whom died from starvation. These eight men were then eaten by the famished soldiers in the castle. Eventually the castle was surrendered to Bruce’s men.

In late 1316, Robert the Bruce sailed from Loch Ryan and arrived at Carrickfergus, bringing with him 7,000 men, and pledged to Edward that together they would now overrun Ireland. The campaign that began in February 1317 caused huge destruction, but achieved very little for the Bruces. Having marched to Dublin, but not attacked it, the Bruce army set about a campaign of devastation, destroying the estates of the leading Anglo-Norman lords in Ireland. Marching to Limerick, the Scottish army was responsible for ‘laying waste the entire country’ and ‘burning, slaying, plundering, spoiling towns, castles and churches’.

The Scots army was starving, and many died of hunger while others resorted to eating their horses. There was no major battle fought in Ireland during Robert Bruce’s campaign here. The Scots army did not lay siege to any walled town anywhere on the island. If Robert the Bruce had hoped that the Gaelic chiefs would rally to the cause and help him in overthrowing English power in Ireland, he was wrong. Sir Edmund Butler’s oncoming Anglo-Norman army, totalling about 30,000 men, grew stronger, and the Bruces had to retreat northwards.

The Robert the Bruce monument at Bannockburn. Robert joined his brother Edward at Carrickfergus in late 1316, and the following February the two ‘brothers in arms’ began a major campaign to drive the Anglo-Normans from Ireland. However, the campaign failed.

14 October 1318: Battle of Faughart

After three-and-a-half years the Bruce campaign ended disastrously in defeat at the Battle of Faughart on 14 October 1318 with Edward Bruce himself killed in the fighting. In the autumn of that year he had led his men towards Dundalk, possibly in search of food and supplies in the face of severe famine conditions. Two miles outside Dundalk, the Scots army (with some support from the de Lacys) squared up to an Anglo-Norman force commanded by John de Bermingham.

In the ensuing battle the Scots were routed and Edward Bruce was killed by Sir John Maupas. Many of the leading men in the Scottish army were killed including both Macruari and Macdonald who died leading their respective cohorts of ‘gallowglass’ warriors. Sir Philip Mowbray escaped from the battlefield at Faughart badly wounded and returned to Scotland to bring the news of Edward’s death to his brother King Robert. Domhnall O Neill was also fortunate to escape with his life.

Few of the Irish mourned Bruce’s death at Faughart. The record of Edward’s death in the Annals of Ulster states that ‘...there was not done from the beginning of the world a deed that was better for the Men of Ireland than that deed. For there came death and loss of people during his time in all Ireland in general for the space of three years and a half and people undoubtedly used to eat each other throughout Ireland’.

The remnants of Edward’s army headed back towards Carrickfergus, pursued by de Bermingham’s men. On reaching the coast they boarded ships and returned to Scotland. It was the end of the campaign. The threat from Scotland, whether real or imagined, continued for some time afterwards, and even the area around Carrickfergus was subject to occasional Scottish raids. However, there was to be no further Bruce-instigated invasion of Ireland.

The view from Faughart towards the Cooley Peninsula, County Louth.

Edward Bruce’s Grave at Faughart

Edward Bruce was killed in the fighting at Faughart and his body afterwards quartered with his head sent to Edward II. A strong tradition persisted, however, that he was buried in the old graveyard at Faughart. In 1824, Sir John Macneill, who was born in this neighbourhood and was of Scottish ancestry, tried to discover whether the remains of Edward Bruce were interred here and began to excavate in the old graveyard. However, he ceased when it became apparent that he was creating consternation among the local people.

At different times in the nineteenth century there were suggestions that a permanent marker should be erected at Faughart to commemorate Edward Bruce. In 1856, someone styling himself ‘A True Scot’ wrote to the Belfast Morning News asking people to ‘take a look at the neglected grave of the brave Edward Bruce, brother of their King Robert Bruce … now without a mark of interment’. In the early 1860s there was apparently a meeting in Edinburgh to discuss having ‘a monument erected at Faughart to the memory of Edward Bruce,’ but nothing further seems to have been done about this.

In 1885, the local parish priest wrote to the Glasgow Herald encouraging its readers to collect subscriptions for ‘a pillar stone of polished granite, with a suitable inscription recording the date and manner of his death, or a memorial gateway, or both, according to circumstances.’ In the 1960s a flat stone was placed over what was believed to be the grave of Edward Bruce. In recent years a new marble plaque was placed at the head of the grave which records, in English and Irish, ‘Edward Bruce, King of Ireland. Killed in Battle of Faughart, 14th October 1318.’

The flat stone on the reputed grave of Edward Bruce.

Looking Back 700 Years On

Even after the ignominious end to the campaign in 1318, Robert Bruce continued to maintain an interest in Ireland, even visiting the island on at least two occasions near the end of his life. It is known that in 1327 he visited Glendun on the east coast of County Antrim, and landed at Larne the following year. Also in 1328 he proposed holding a meeting at Greencastle in County Down to agree a peace treaty between the English and the Scots.

The Bruce campaign in Ireland was brutal and Edward Bruce was no heroic figure. It would be wrong, therefore, to romanticise this period. However, this story does present us an opportunity to discover more about our medieval past and to understand about the events and processes that have contributed to the history of Scotland and Ulster and the relationships between them.

What If?...

The story itself throws up all sorts of ‘What ifs?’ For example, at the Ayr parliament of 1315 Edward was named as the successor to the throne should his brother die without male heir. This raised the distinct possibility of Edward Bruce becoming King of both Scotland and Ireland at the same time – had, of course, the invasion succeeded and Robert died without male issue. How different might the history of Ireland have been?

In terms of the importance of the story to Scottish history, the modern consensus amongst historians is that the invasion of Ireland ultimately served its purpose as Edward II of England was deflected by events in Ireland from his intended new landward invasion of Scotland. This gave Robert Bruce the time needed to consolidate his claim with the Pope, as embodied in the Declaration of Arbroath (April 1320), to be the rightful King of an independent Scotland – a right that would be passed on to his heirs. This was finally conceded by Edward III by the Treaty of Northampton, a year before Robert’s death.

Greencastle, County Down (with the Mourne Mountains behind); the location of Robert Bruce’s proposed peace treaty negotiations of 1328.

Bruce’s Allies Who Later Settled In Ulster

The Bruce campaign failed, but after they had returned to Scotland in 1318, the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster was severely weakened. Around 1350 a branch of the O Neills moved eastwards into County Antrim and County Down. The Clandeboye O Neills held much of east Ulster for the next 300 years.

It was in 1605 that two other Ayrshiremen, James Hamilton and Hugh Montgomery, struck a deal with the O Neills for two major tracts of land in County Down. They invited many Scottish families to become tenant farmers, some of whom were descendants of Bruce’s allies.

A detailed list of those allies to whom Robert Bruce granted land in reward for service is available online, entitled An Index, Drawn up about the Year 1629, of many Records of Charters, Granted by Different Sovereigns of Scotland Between the Years 1309 and 1413, which was published by William Robertson of Edinburgh in 1798.

The Boyds of Kilmarnock (a Robert Boyd was granted land at Kilmarnock by Robert the Bruce) and the Adairs of Kinhilt near Stranraer (a Thomas Edzear was granted lands at Kildonan) were just two of those families to relocate to Ulster in the early 1600s, retracing the footsteps of their ancestors who had fought for the Bruces. This generation of Scots would settle permanently in Ulster, paving the way for tens of thousands more over the following centuries.

Dunskey Castle near Portpatrick, once home to the Adairs of Kinhilt.

The Boyds were allies of Robert Bruce. He granted them lands at Kilmarnock and other parts of Ayrshire as a reward for their loyalty. They built Dean Castle at Kilmarnock and also Portencross Castle near West Kilbride. Almost 300 years later, many of the Boyds migrated to east Ulster during the ‘Hamilton & Montgomery Settlement’ which began in 1606.

The Bruces In Ireland: Literary References

In the centuries since 1315, the story of Edward Bruce and Robert Bruce’s campaign in Ireland has been told many times by poets, historians and novelists. In 1826, the Larne-born poet William Hamilton Drummond published the 128-page Bruce’s Invasion of Ireland; a Poem.

Another academic with south Antrim origins, Sir Samuel Ferguson, wrote an historical story in 1833 about the O Neills, set 500 years earlier in 1333, during the period after the Bruce campaign. Entitled The Return of Clandeboye it touches on the O Neill alliance with the Bruces.

Belfast publisher William McComb travelled to the site of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1826, and later published a poem entitled Bannockburn: written on the Field in the Summer of 1826.

In the 1800s, Sir Walter Scott did more than any other writer to popularise the key figures and events from Scottish history. In his famous collection, Tales of a Grandfather, he wrote the following:

"You will be naturally curious to hear what became of Edward, the brother of Robert Bruce, who was so courageous and at the same time so rash. You must know that the Irish at that time had been almost fully conquered by the English; but becoming weary of them, the Irish chiefs, or at least a great many of them, invited Edward Bruce to come over drive out the English and become their king. He was willing enough to go, for he had always a high courageous spirit, and desired to obtain fame and dominion by fighting. Edward Bruce was as good a soldier as his brother, but not so prudent and cautious; for, except in the affair of killing the Red Comyn, which was a wicked and violent action, Robert Bruce, in his latter days, showed himself as wise as he was courageous. However, he was well contented that his brother Edward, who had always fought so bravely for him, should be raised up to be King of Ireland."

Sir Walter Scott

Sir Samuel Ferguson

Depiction of Edward Bruce on the arrival signage at Connor, County Antrim.

Depiction of Robert Bruce on the arrival signage at Lochmaben, Dumfries & Galloway.

Find out more

READ

Colm McNamee, The Wars of the Bruces (2006)

Colm McNamee, Robert Bruce, Our Most Valiant Prince (2006)

Sean Duffy (ed.), Robert the Bruce’s Irish Wars (2002)

G. W. S. Barrow, Robert Bruce (1965)

Roger Chatterton-Newman, Edward Bruce, a Medieval Tragedy (1992)

FREE ONLINE BOOKS (available from www.archive.org)

John Barbour, The Brus, The History of Robert the Bruce King of Scots (c. 1375)

William Hamilton Drummond, Bruce’s Invasion of Ireland; a Poem (1826)

Caroline Colvin, The Invasion of Ireland by Edward Bruce (1901)

Olive Gertrude Armstrong, Edward Bruce’s Invasion of Ireland (1923)

Blind Harry, or Henry the Minstrel, The History of Sir William Wallace (various editions)