Masters of the Sea

Belfast's Ulster-Scots Shipbuilders

Belfast is a maritime city of global trade and emigration to the four corners of the world.

Even in the early 1600s when our city was still just a village, Belfast’s merchants were mostly Scottish and traded with North America (tobacco), the West Indies (sugar) and Spain (wine). A ship built in Belfast Lough in 1636, the Eagle Wing, attempted to cross the Atlantic Ocean. In 1778, the U.S. Navy won its first victory here in Belfast Lough. Much of the Allied war effort during two World Wars came from our shores and shipyards.

Travel along the coastal routes out of Belfast and on a clear day you will easily see Scotland, just 13 miles away at the closest point. The nautical ‘highway’ of the narrow sea between Scotland and Northern Ireland forged a kinship which still connects our coastlines and made a seafaring people who built a truly world-class shipbuilding industry.

Commercial shipbuilding comes to Belfast from Ayrshire in Scotland

Origins

The Ritchie brothers started a successful shipyard in Saltcoats on the Ayrshire coast in 1775. However, they had many competitors and when William visited Belfast in March 1791 he saw a golden opportunity – all of the ships in Belfast were being bought from Scotland and England. On 3rd July he came back with his brother Hugh, ten Scottish workers, equipment and materials, and set up the only shipyard in Belfast, on the banks of the River Lagan. Today the site of his shipyard is occupied by the grand offices of the Belfast Harbour Commissioners and his original dock is buried beneath Corporation Square outside.

As Presbyterians, the Ritchies fitted easily into the civic life of Presbyterian Belfast. A French aristocrat who visited in 1797 wrote ‘Belfast has almost entirely the look of a Scotch town, and the character of the inhabitants has considerable resemblance to that of the people of Glasgow.’

Portrait of William Ritchie, 1756–1834

A painting of Ritchie’s Dock by D Stewart

The First Ritchie Ship Sails To New York

In July 1792 they launched their first ship, the Hibernia (said to have been named as a sign of support for the ‘United Irishmen’ cause of the 1790s which was dominated by Presbyterians). It had an ‘American bottom’ hull design. As her maiden voyage was to New York, this design shrewdly exploited a loophole in American customs duty and meant that the Belfast merchants would benefit from an attractive 5% discount on the duty due on goods they exported into the United States.

Dry Dock Built

On New Year’s Day 1800 the new century began with the opening of a new ‘dry dock’ in Belfast, built by the Ritchies and named ‘No. 1 Graving Dock’. It allowed three ships to be docked at the same time. It survives today, behind the Belfast Harbour Commissioners offices, a clue to the existence of the Ritchie Shipyard it used to lie beside. The Ritchies built over 40 ships; Belfast vessels were now trading regularly with North America and the Caribbean.

Alexander McLaine from Scotland founds a new company with John Ritchie

The Scottish Influx Continues

Hugh Ritchie set up his own shipyard in 1798 but he died a few years later and was succeeded by another brother, John Ritchie, who came over from Saltcoats to Belfast in 1807. John later joined forces with another Scot, Alexander McLaine, who was originally from the Isle of Skye, another seafaring part of the west coast of Scotland. Together they founded ‘Ritchie and McLaine’ in 1811 which operated from a yard near today’s Pilot Street. McLaine later married John’s daughter, Martha Ritchie.

Arrival Of The Steamships

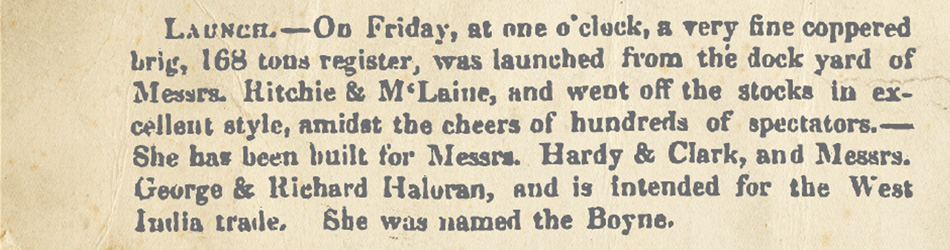

Pushing the boundaries of innovation, Ritchie & McLaine built Belfast’s first steamship, the Belfast, which was launched in 1820. In 1828 they launched a copper-bottomed vessel named the Boyne, designed for transatlantic trade with the West Indies. Sadly that same year John Ritchie died, and the fortunes of the firm were taken forward by McLaine. The firm was renamed ‘Alexander McLaine and Sons’.

When Alexander McLaine died he was buried at Clifton Street Cemetery in the same grave as John Ritchie. An impressive monument to both men and their families can be seen there today.

John Ritchie, 1751–1828

1815 Charles Connell & Sons of Belfast And Glasgow

Successors to the Ritchies: full-rigged ships, tea from China and a ‘floating palace’

Charles Connell, another Ayrshire shipbuilder, came to Belfast to work for the Ritchies around 1815. His wife, Ann Hamilton, and almost all of their children came too – however their eldest son John remained in Scotland. Charles became manager of Ritchie’s yard, and when William Ritchie retired Connell continued to run the yard. When Ritchie died in 1834 Connell took the company over, renaming it ‘Charles Connell & Son’. Their first major contract was to remove a stranded ship which was blocking the entrance to Belfast harbour. Connell summoned every soldier from the Belfast garrison to pull the ship with ropes, far enough to re-float.

Global Trade

Their first ship was a schooner, Jane, launched in 1825, and soon they were building ships for global trade. The Fanny was the first ship to bring tea to Belfast from China. It was said that ‘the shipping of Belfast extends over every part of the world where shipping can go’. The Aurora was launched in 1838, the biggest vessel ever built in Belfast up to that time. She was built for another Scottish firm with Ulster connections - George and John Burns of Glasgow. A crowd of 15,000 people gathered for the launch. Aurora broke the record for travel between Belfast and Glasgow and such was the luxury of her craftsmanship she was described as a ‘floating palace’.

The Connells who had stayed in Scotland also founded a shipyard. This entrepreneurial family had two companies in the thriving, world-class, Ulster-Scots shipbuilding industry, both bearing the name Charles Connell and Sons. Charles Connell was succeeded by his eldest son, Alexander (Sandy) Connell. The family’s connections with Belfast’s maritime industry continue to the present day.

The launch of the Aurora from Belfast Harbour, by Hugh Frazer

Linen Hall Library

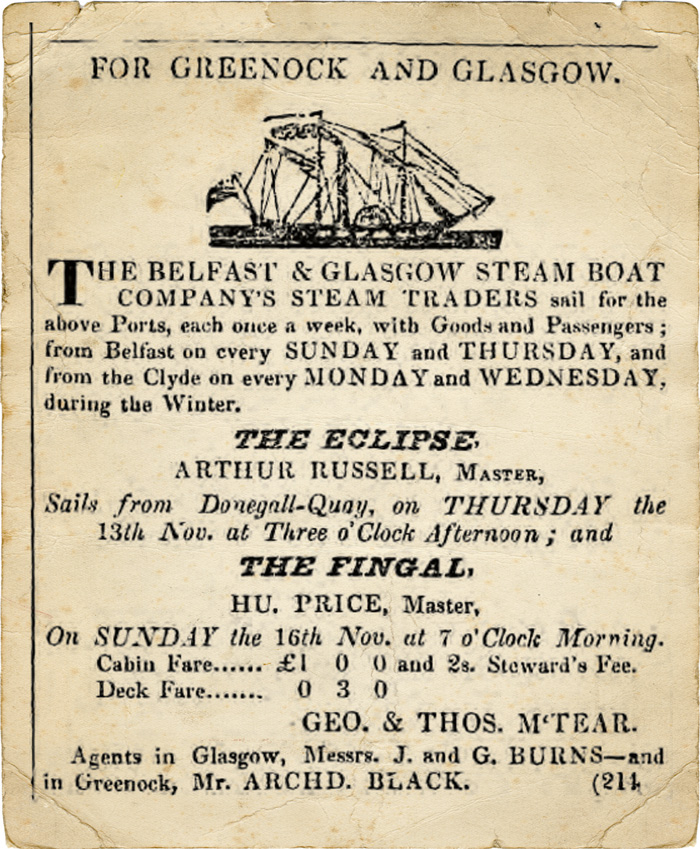

The McTear brothers of Hazelbank establish a steamship service to Scotland

Covenanter Roots

Thomas and George McTear traced their ancestry back to Scotland, to Noah McTear from Perthshire who was a Presbyterian Covenanter during the ‘Killing Times’ of the mid 1600s. He fled to Ulster for refuge and his descendants prospered in Belfast. The McTears lived in a large family home on the shores of Belfast Lough known as Hazelbank. It was from here that they could watch the changing design of vessels, as steam power replaced sailing ships.

Company Founded

Still young men in their early 20s, they joined forces with Robert Patterson Ritchie (the only son of John Ritchie of Ritchie & McLaine) around 1820 and founded the Belfast-Glasgow Steamship Company. Robert Ritchie was sent to Scotland to oversee the construction of their first ship, the Fingal – a famous character in the ancient myths of Scotland and Ireland. The Fingal was launched in March 1826, sailing between Belfast and Glasgow four times a week. One of the vessel’s most notorious passengers was the wife of body-snatcher William Hare. In 1833 a storm arose and a New York actor named James Wallack heroically organised the rest of the passengers to man the pumps to keep Fingal afloat until she reached safe harbour at Greenock.

The Burns Brothers

The company’s agents in Glasgow were James and George Burns – they later acquired the agency for Cunard Line’s steamers which sailed to New York and Halifax, Nova Scotia. Many decades later the Burns brothers bought the company from the McTears, which eventually became the Burns & Laird Line, a brand name which dominated the Ulster/Scotland shipping routes until the 1970s.

Thomas McTear

Advert from November 1828

1857 The Origins Of The World’s Greatest Shipyard

‘Gentleman apprentices’ Walter and Alexander Wilson join the shipbuilding industry

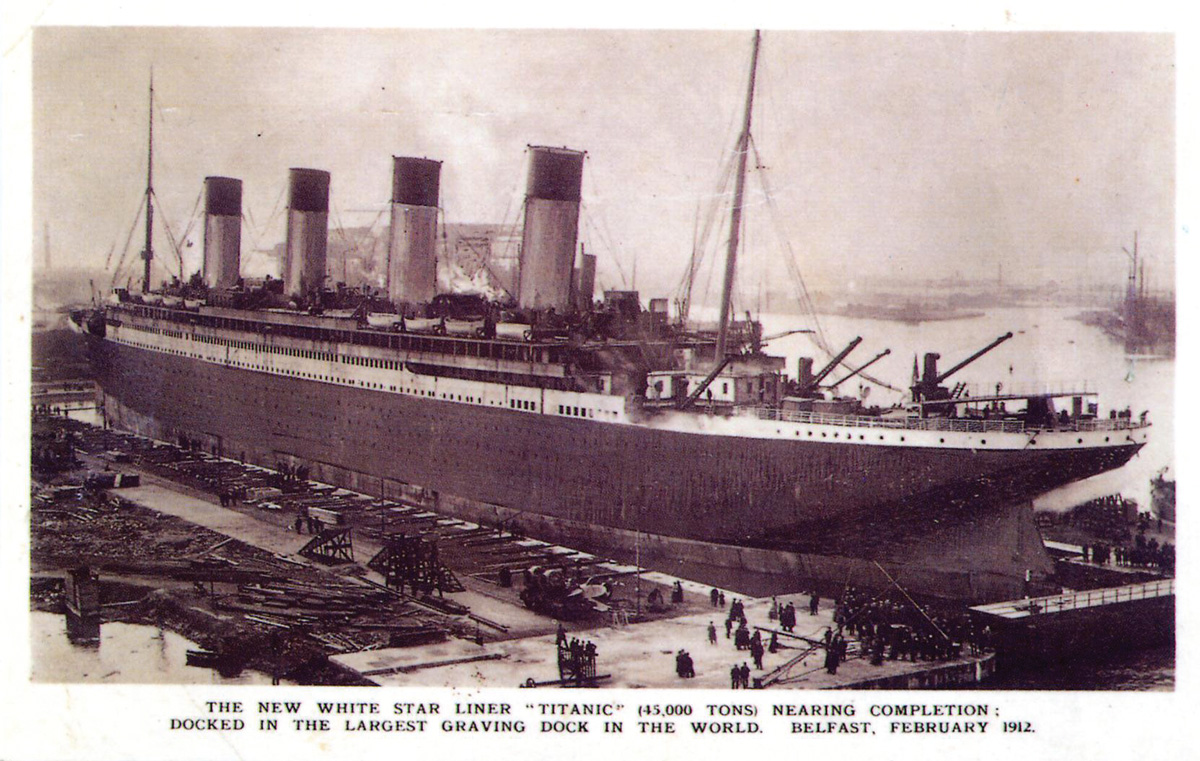

The most famous names in Belfast shipbuilding history are of course Harland & Wolff, the name of the greatest shipyard in the world - and the yard where Titanic was built. Yet ‘The Big Yard’ grew steadily from humbler origins.

Scottish Roots Shared With A President

Walter Henry Wilson and his brother Alexander entered the shipbuilding trade in 1855 when they joined as ‘gentlemen apprentices’. Their paternal grandfather was Walter Wilson of Croglin in Dumfriesshire, Scotland. He moved to Ulster and became involved in the linen industry at Ballydrain between Belfast and Lisburn. The 28th President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, also claimed descent from the same Scottish family. The Wilson brothers’ other grandparents were also either Scottish or of Scottish descent.

York Street - Home Of The Wilsons, Edward Harland And Gustav Wolff

The brothers were born at Maryville on the Lisburn Road in Belfast and educated at the Moravian College at Gracehill near Ballymena. Following their father’s death, the family home had to be rented out and, along with their mother, they moved to rooms in York Street in Belfast’s thriving maritime district. They started work at Robert Hickson’s shipyard in 1857, under the supervision of Edward Harland, who also lived in York Street. Another neighbour, just across the road in Brougham Street, was an ambitious young man called Gustav Wolff.

The next year Hickson’s yard was taken over by Harland; it was renamed ‘Harland and Wolff’ in 1861. Walter Henry Wilson became one of the top draughtsmen in the company and in 1874 he became a board director. Walter Wilson was general manager and his brother Alexander was in charge of engine design. In 1882 the company’s 150th ship was named Walter H Wilson in honour of his contribution to the firm.

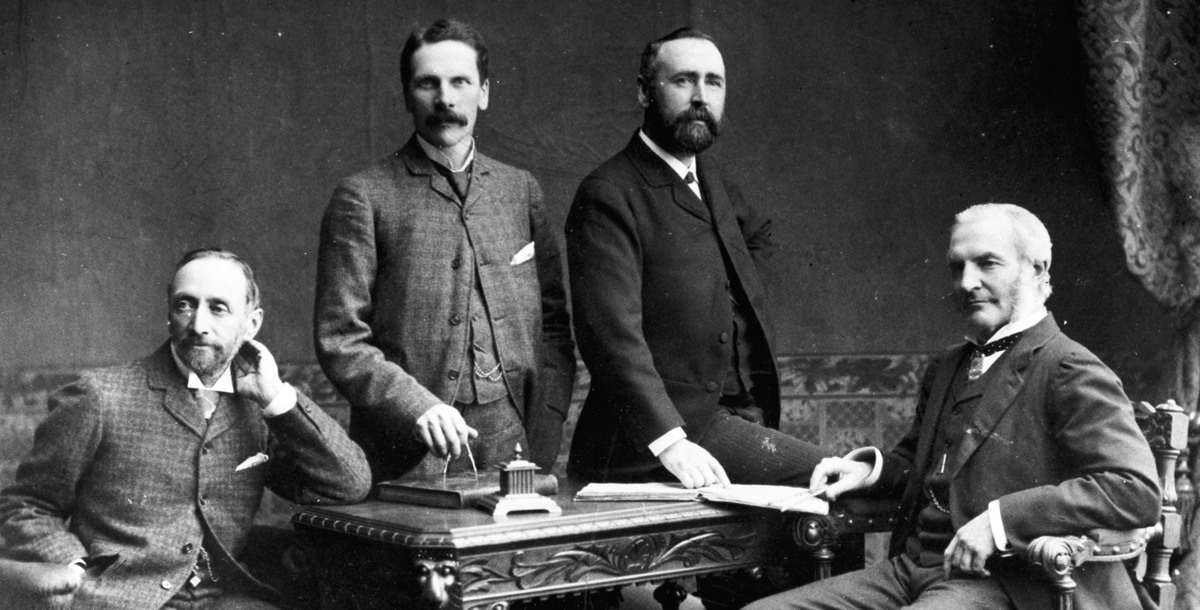

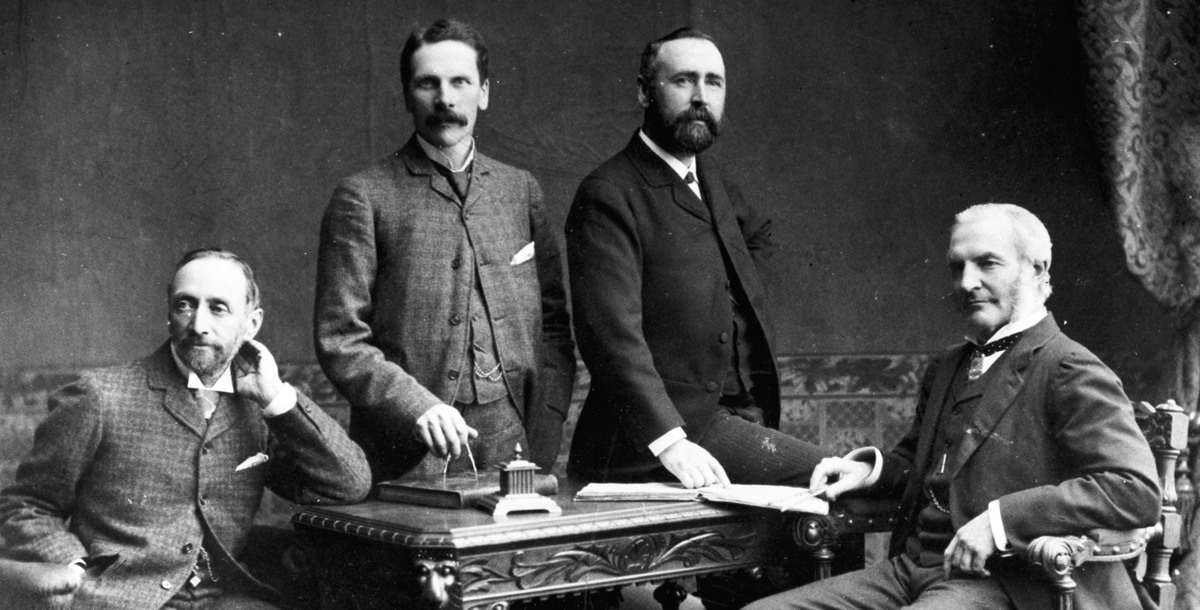

The directors of Harland & Wolff - (L-R) Wolff, Wilson, Pirrie and Harland

IIIB-Harland © National Museums Northern Ireland Collection Ulster Museum

William Pirrie, another ‘gentleman apprentice’, becomes Ulster’s leading industrialist

Although William was born in Canada, his grandfather and namesake, Captain William Pirrie, was from Port William in Galloway, Scotland. After a spell in America he settled in Ulster, becoming a Belfast Harbour Commissioner in 1849. He sent his son James over to Canada to start a timber business but James died a few years later. His widow Eliza and two young children, Eliza and William (then aged 2), returned home and lived with Captain Pirrie in Conlig.

Young William was hugely influenced by his grandfather’s interest in ships and when he left school in 1862 aged 16 he joined Harland & Wolff as a premium apprentice. His rise in the firm was meteoric. Just 12 years after joining Harland & Wolff, he became a partner in 1874. Eventually he became chairman of the company and it was under his leadership that the firm opened a shipyard on the Clyde in 1902.

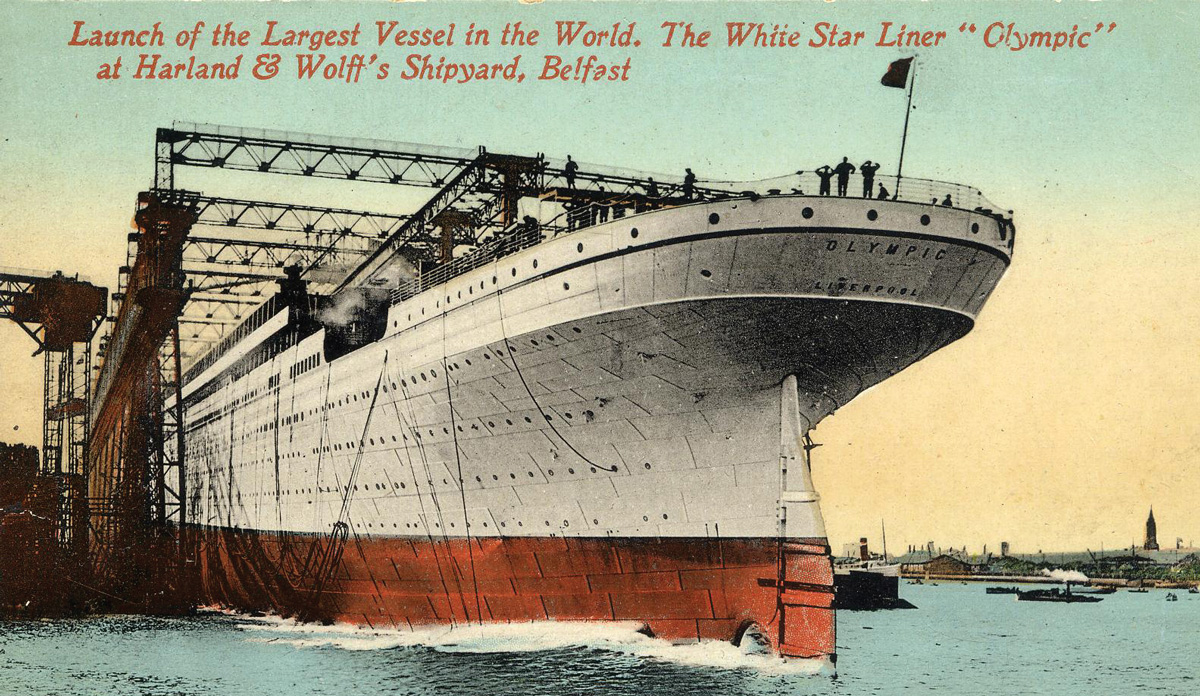

It was in July 1907, over dinner at his grand London residence, that Pirrie and Bruce Ismay of White Star Line conceived a plan to build the largest liners in the world – the Olympic, the Titanic and the Britannic, in an effort to eclipse Cunard Line.

Pirrie served on Belfast Corporation and was Lord Mayor from 1896–7. He was also the first person to receive the Freedom of the City in 1898. Elevated to the peerage as a Baron in 1906, he became Viscount Pirrie of Belfast in 1921. He was appointed to the Senate of the new Northern Ireland Parliament in the same year.

He died while on business in Buenos Aires in 1924 and his body was brought home from New York onboard the Olympic. He was buried in Belfast City Cemetery.

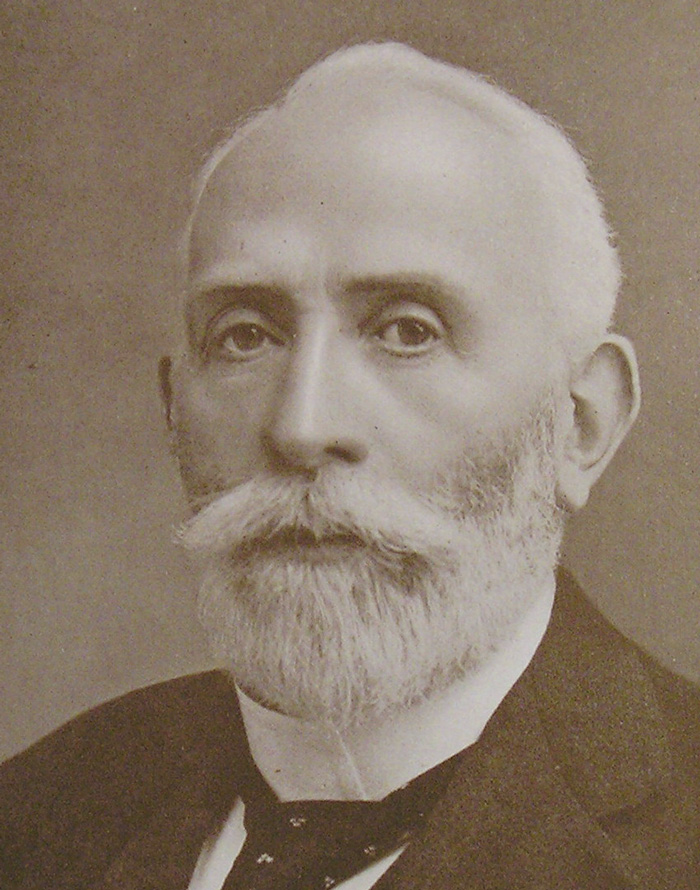

William Pirrie pictured in 1903

Titanic and Olympic

The Titanic influence of Alexander Montgomery Carlisle of Ballymena

Ulster-Scots Roots

Alexander Montgomery Carlisle was a first cousin of William Pirrie and also his brother-in-law; Pirrie married Margaret Montgomery Carlisle in 1879. On their paternal side, the Carlisles were Presbyterians from County Down – on their maternal side, like Pirrie, they were descended from the renowned Ulster-Scots Montgomeries of Killead, County Antrim.

Apprentice and Managing Director

Alexander Carlisle joined Harland & Wolff in 1870; he succeeded Pirrie as head draughtsman and in 1878 became shipyard manager – Pirrie said he was the greatest shipyard manager in Europe. He eventually became Managing Director of the company. He retired early, failed in an attempt to start a political career, and moved to London. He was retained by Harland & Wolff and he advised on the design of the Olympic and Titanic, influencing the young Thomas Andrews.

Photo courtesy of Belfast Shipbuilders a Titanic Tale, Stephen Cameron, Colourpoint Books

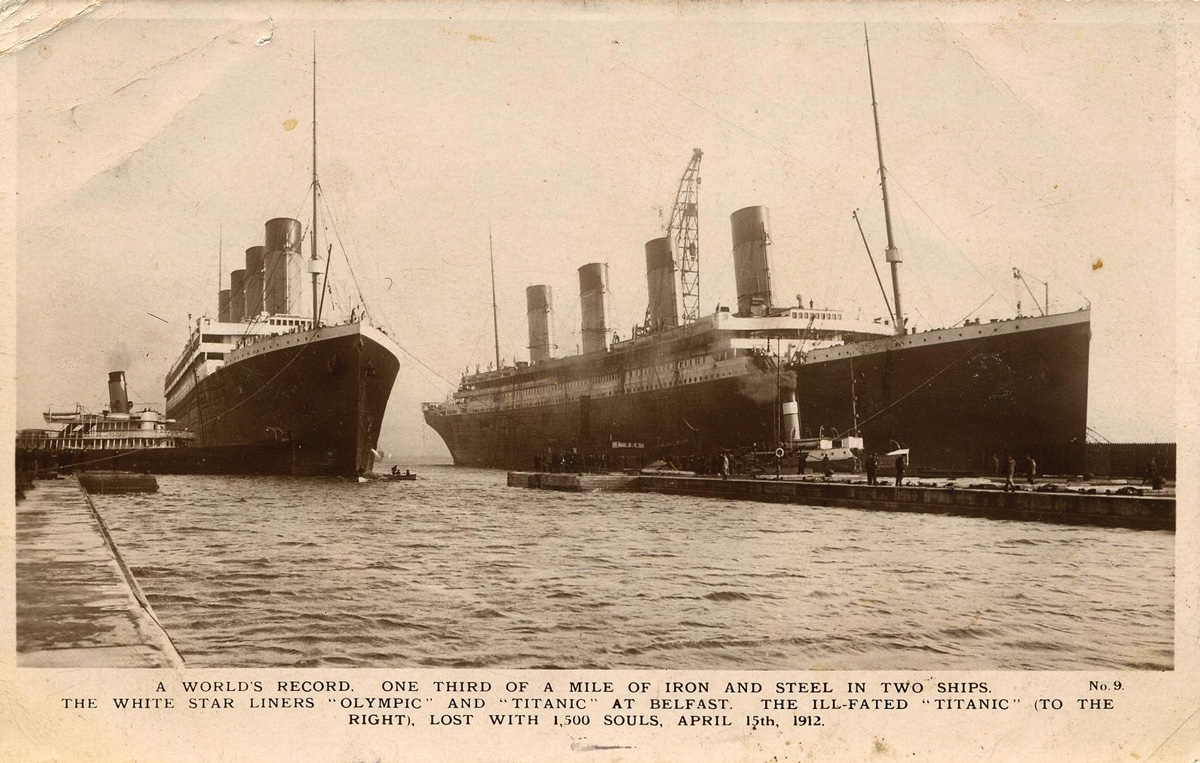

A postcard celebrating the launch of Olympic on 20 October 1910, then the world’s largest ship

Lifeboat Design Rejected

Significantly, Carlisle suggested a new design which would enable the ships to carry four times more lifeboats than the law required, but this was rejected by White Star Line. Tragically, the shortage of lifeboats was a major factor in the huge loss of life when Titanic sank. He was heartbroken by the disaster.

He retained high-level political connections - he offered to mediate in the War of Independence in Ireland in the 1920s, and had a close relationship with Kaiser Wilhelm II of Germany. He died in 1926 in London, where his memorial tablet at Golders Green bears the simple inscription ‘Shipbuilder – Belfast’.

Ulsterman Frank Workman joins forces with Scotsman George Clark

Harland & Wolff was not Belfast’s only successful shipyard. Belfast man Frank Workman – whose roots can be traced to the small port of Saltcoats in Ayrshire, where the famous Ritchies had also originated – joined Harland and Wolff in 1874.

Ayrshire, Paisley, Edinburgh & Glasgow

Five years later he and a colleague, William Campbell, set up their own shipyard; the following year a young Scot called George Smith Clark from Paisley in Scotland joined them. Clark had been educated at Merchiston Castle School in Edinburgh around the same time as James Craig, the future Prime Minister of Northern Ireland. In 1880 the Workman Clark Shipbuilding Company was born.

One of their earliest ships – the Polly Woodside - was launched in 1885. Today it is in Melbourne, Australia. The engines for their ships were brought in from Scotland, until they set up their own engine works under the stewardship of Charles Allan of Glasgow.

The Great War

120 of the firm’s workers were killed in action during the Great War, including Frank Workman’s only son Edward. A war memorial was built to commemorate their sacrifice. At its peak in 1919 Workman Clark had 10,000 employees and during the company’s existence they built 535 ships. In the early 1920s the yard was bought by an English firm and Workman and Clark retired. The firm’s fortunes subsequently declined and it closed in 1935.

Presbyterians and Politics

Both men had political interests and were from Presbyterian backgrounds. Workman served on Belfast Corporation and as High Sheriff of Belfast in 1913. He was heavily involved in Belmont Presbyterian Church.

Clark, who was a member and major benefactor of Fortwilliam Presbyterian Church, presided at the inaugural meeting of the Belfast Scottish Association in 1888, was elected MP for North Belfast in 1907 and became Sir George Clark, Baronet of Dunlambert, Belfast in 1917. Like William Pirrie, Clark became a Senator in the new Northern Ireland Parliament.

George Clark

Polly Woodside, launched in 1885, is now on display in Melbourne, managed by the National Trust of Australia

1912 Titanic Designer Who Sank With His Masterpiece

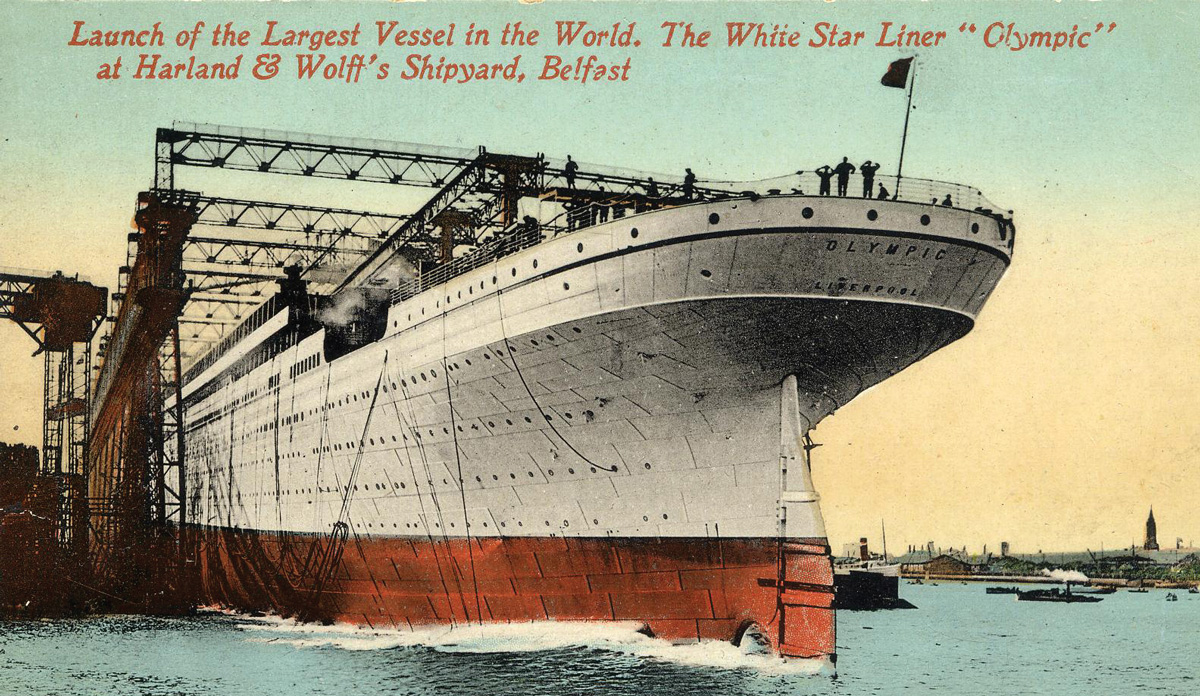

The talent and tragedy of Thomas Andrews, the ‘golden boy’ of an old Ulster-Scots family

Thomas Andrews’ place in history is as the man who designed, and died onboard, the Titanic. The Andrews family can trace its roots back to 1698, although there were Andrews in their small country home town of Comber as early as the 1630s, probably having come over from Scotland as tenants of the Ulster-Scots ‘Founding Father’ Sir James Hamilton of Ayrshire, to the County Down estates he acquired in 1606.

A Family of Influence

Thomas’ mother Elizabeth was William Pirrie’s sister, and like Pirrie, Andrews was educated at Royal Belfast Academical Institution. Thomas’ father, also called Thomas Andrews, was director of a spinning mill in Comber and a prominent figure in Ulster society, holding many civic positions.

The Young Protegé of Pirrie And Carlisle

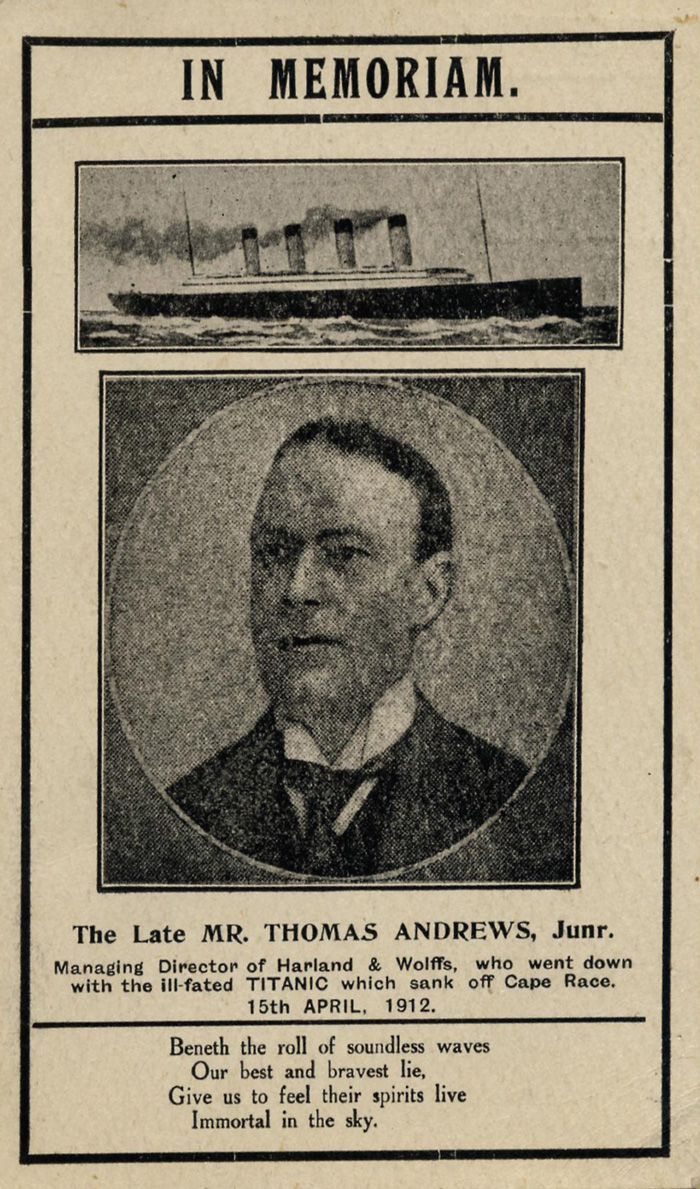

Thomas Jr. joined Harland & Wolff in 1889 as an apprentice; by 1907 he was Managing Director and head of the draughting department. He started to work on three vast ships for White Star Line – Olympic, Titanic and Britannic – alongside his uncle, William Pirrie, and second cousin, Alexander Montgomery Carlisle. When Olympic launched Andrews sailed on her maiden voyage; he did likewise on his second ship, Titanic. The ships were masterpieces of engineering and luxury – breathtaking in scale and quality. However their client, Bruce Ismay of White Star Line, interfered with the design recommendations of Pirrie, Carlisle and Andrews, insisting on just 16 lifeboats rather than the recommended 48.

When disaster struck, Andrews realised the ship was doomed and he helped to organise passengers into the lifeboats. Had there been 48 lifeboats all on board would have been saved. Tragically Andrews, along with 1,511 crew and passengers, drowned in the icy Atlantic.

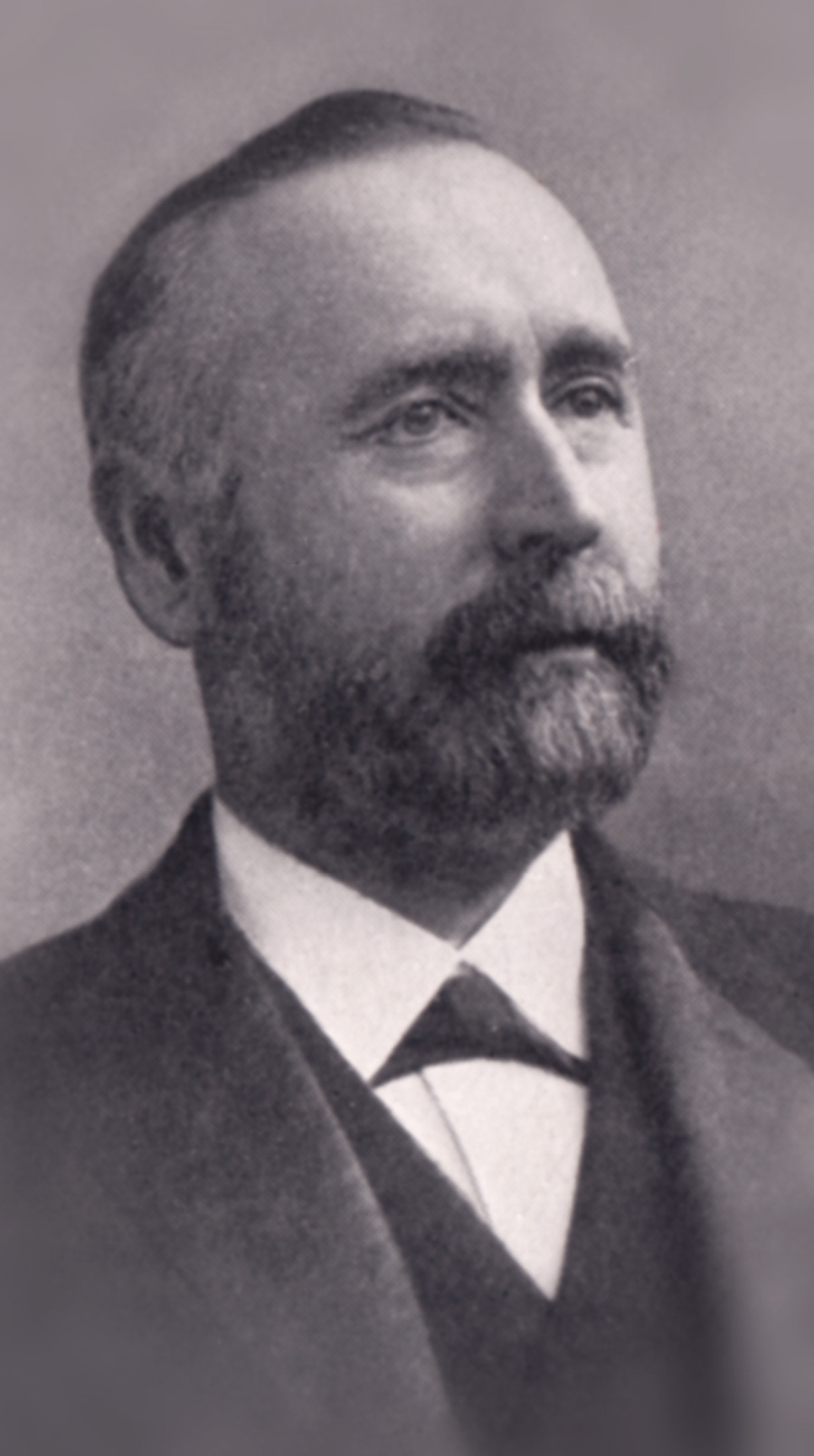

Thomas Andrews

A postcard showing Titanic in February 1912 in the largest graving dock in the world