The Scotch-Irish And Savannah

The Scotch-Irish story in Savannah is not as well known or as prominent as in other places in America. Nonetheless, it is still part of the fabric of the city’s history. People with roots in Ulster were settling in Savannah and its hinterland from the 1730s. Others followed in the nineteenth century. Together the Scotch-Irish have made a major contribution to the economic, religious and cultural life of the city. This exhibition tells you something of their story.

Transatlantic Kinfolk: From Ulster To America

The origins of the movement of Scotch-Irish families to America can be traced to the seventeenth century and was well underway by the 1680s. A high proportion of the earliest emigrants were from north-west Ulster and many of them settled in the region of Chesapeake Bay. Their reasons for leaving included economic pressures and religious persecution due to their Presbyterian beliefs.

Ireland: An Island Of Cultural Variety

Throughout its history, Ulster, the northern province of Ireland, has been a place where many different peoples have left their influence. In the last millennium Vikings, Anglo-Normans, Huguenots, Moravians, Italians, Jews and many others have settled here. The strongest cultural influences, however, have been English, Irish and Scottish, a triple blend that has given Ulster its distinctive character.

Three Names For The Same People

Ulster-Scots, Scotch-Irish and Scots-Irish are three names for a people whose origins can be traced to Scotland. In Ulster, where they settled in large numbers in the 1600s, they are known as the Ulster-Scots. In America, they are known as the Scotch-Irish or Scots-Irish. All three terms have a long pedigree – the earliest recorded use of ‘Scotch-Irish’ can be found in Maryland in 1690.

The Scotch-Irish And America

Over the centuries Scotch-Irish families have travelled to every corner of the globe in search of new lives and new opportunities. In the United States their influence has been huge and their legacy includes pioneers, presidents, military commanders, religious leaders, educators, philanthropists and giants of industry and commerce.

Migration In The 1700s

Emigration from Ulster to America accelerated in the late 1710s. In 1718 over 100 families set sail from Ulster for New England. By this time significant numbers of families were also moving to Pennsylvania which would become the main focus of Ulster emigration for decades. From the 1760s ships were sailing regularly from Ulster to Southern ports, such as Charleston and Savannah. Estimates of the numbers leaving Ulster in the 1700s vary, but were perhaps in the region of 120,000–180,000 people. Chain migration was hugely significant as emigrants followed the routes taken by family members and neighbours from home who had gone before.

Emigration from Ulster to America accelerated in the late 1710s. In 1718 over 100 families set sail from Ulster for New England. By this time significant numbers of families were also moving to Pennsylvania which would become the main focus of Ulster emigration for decades. From the 1760s ships were sailing regularly from Ulster to Southern ports, such as Charleston and Savannah. Estimates of the numbers leaving Ulster in the 1700s vary, but were perhaps in the region of 120,000–180,000 people. Chain migration was hugely significant as emigrants followed the routes taken by family members and neighbours from home who had gone before.

Migration Since 1800s

If the numbers emigrating from Ulster to America in the 1700s were impressive, these were dwarfed by the figures for the nineteenth century when possibly as many as 1.5 million people left Ulster for North America. While the destination for many of these migrants was Canada, a clear majority ended up in the United States. Emigration from Ulster in this period was more religiously and culturally diverse. However, the transatlantic migration of the Scotch-Irish remained hugely significant, both numerically and proportionately. The story of the relationship between Ulster and America comes right down to the present as the United States continues to attract many of our young people in search of new opportunities.

If the numbers emigrating from Ulster to America in the 1700s were impressive, these were dwarfed by the figures for the nineteenth century when possibly as many as 1.5 million people left Ulster for North America. While the destination for many of these migrants was Canada, a clear majority ended up in the United States. Emigration from Ulster in this period was more religiously and culturally diverse. However, the transatlantic migration of the Scotch-Irish remained hugely significant, both numerically and proportionately. The story of the relationship between Ulster and America comes right down to the present as the United States continues to attract many of our young people in search of new opportunities.

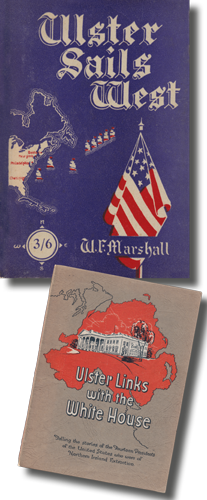

These 1940s publications celebrated Ulster’s links with America at the time when thousands of GIs were stationed in Northern Ireland.

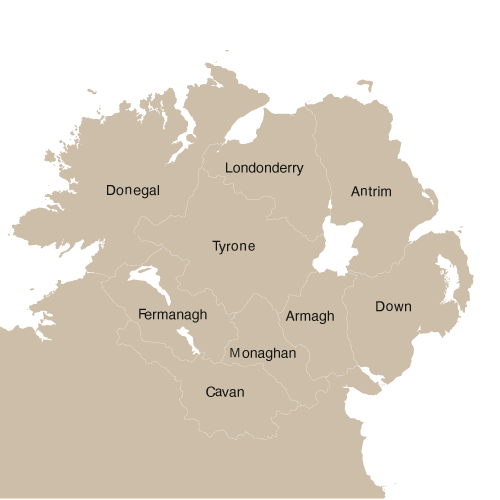

Ulster’s nine counties.

The ‘Father of Black History’

The ‘Father of Black History’, Carter G. Woodson (1875–1950) often wrote warmly of his Scotch-Irish neighbours in Appalachia. He described them as a ‘God-fearing, Sabbath-keeping, covenant-adhering, liberty-loving and tyrant-hating race.’

This love of freedom is a regular theme in centuries of Scotch-Irish literature.

From Woodson’s essay ‘Freedom and Slavery in Appalachian America’, in The Journal of Negro History, April 1916

Carter G. Woodson. Courtesy Scurlock Studio Records, Archives Center, National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution.

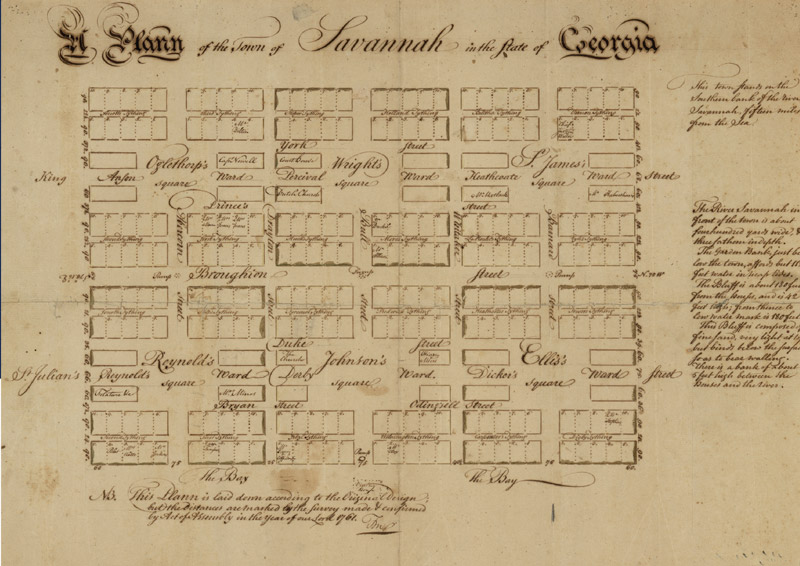

The Ulster Link To Abercorn Street

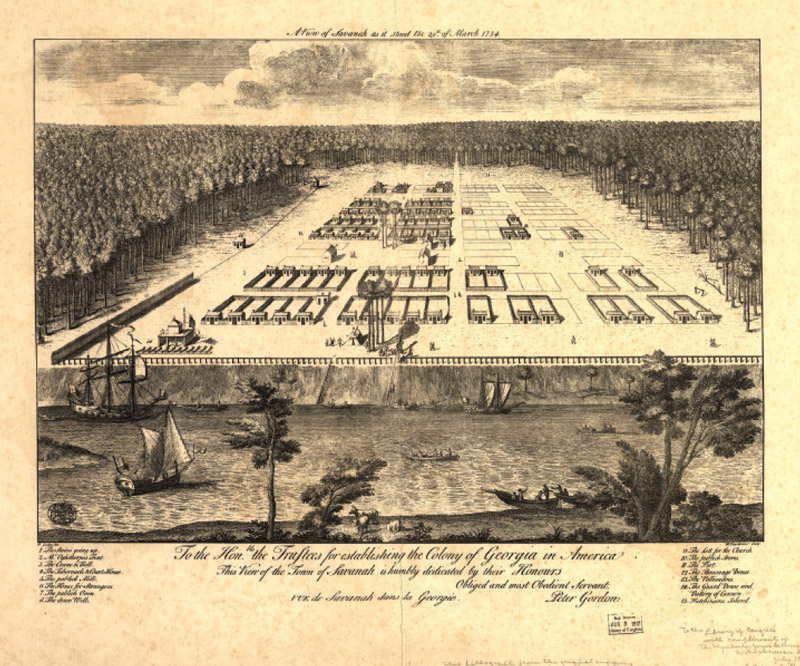

Savannah is well known for its distinctive grid pattern of squares and streets. It has been suggested that when General Oglethorpe laid out the new city in 1733 he was inspired by the seventeenth-century plans of two towns in Ulster, Coleraine and Londonderry. Whether or not there is any truth to this, it does appear that the developers of the Ulster towns and Savannah were drawing on the same Renaissance-inspired ideals of urban planning.

The Earl Of Abercorn

One of the principal streets in the embryonic city was named for James Hamilton, the 6th Earl of Abercorn. Abercorn was one of the main promoters of the Georgia colony project in the early 1730s. He also supported the endeavour financially, providing a number of sizeable donations. His death in 1734 was deeply regretted by those involved in the scheme.

One of the principal streets in the embryonic city was named for James Hamilton, the 6th Earl of Abercorn. Abercorn was one of the main promoters of the Georgia colony project in the early 1730s. He also supported the endeavour financially, providing a number of sizeable donations. His death in 1734 was deeply regretted by those involved in the scheme.

A view of Savannah, 1734.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.Ulster’s nine counties.

The 6th Earl of Abercorn. Courtesy His Grace the Duke of Abercorn KG.

Ulster Landowner

The Earl of Abercorn was a major landowner in Ulster. In the early seventeenth century his great-grandfather, the 1st Earl of Abercorn, a Scottish nobleman from Paisley, near Glasgow, was granted lands in County Tyrone as part of the scheme for the Ulster Plantation. In 1689, before he succeeded to the earldom, he took part in the famous siege of Londonderry when a small garrison held out successfully against a much larger army.

The Earl of Abercorn was a major landowner in Ulster. In the early seventeenth century his great-grandfather, the 1st Earl of Abercorn, a Scottish nobleman from Paisley, near Glasgow, was granted lands in County Tyrone as part of the scheme for the Ulster Plantation. In 1689, before he succeeded to the earldom, he took part in the famous siege of Londonderry when a small garrison held out successfully against a much larger army.

The Village Of Abercorn

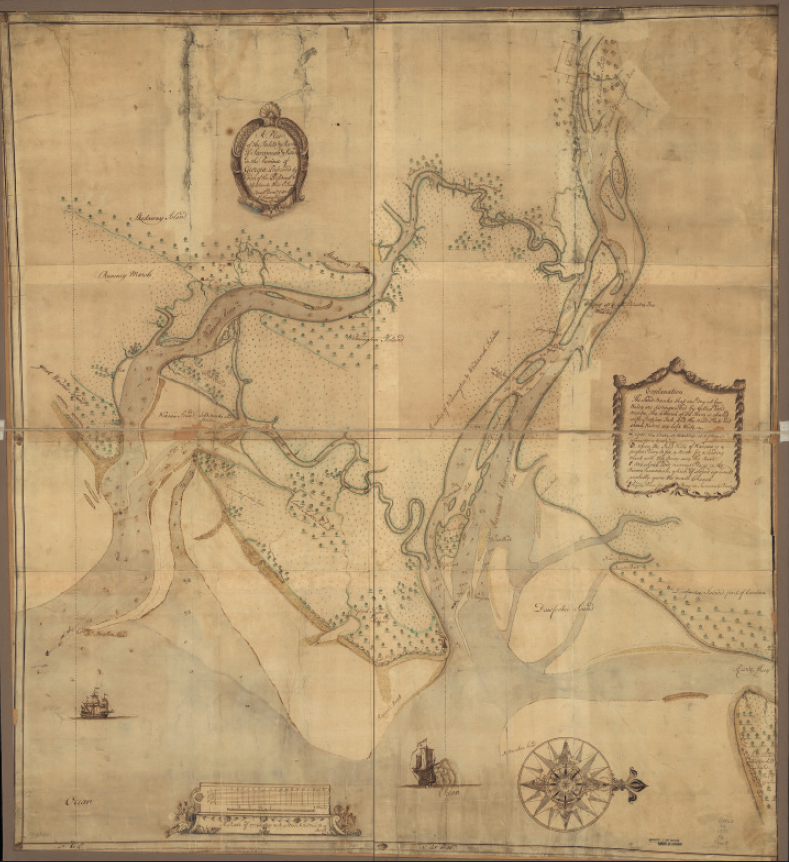

Abercorn was also the name given to a village on the Savannah River. In 1733 ten families were allocated to this settlement and in the following year a number of Salzburgers (German-speaking Protestants from Salzburg in modern-day Austria) settled here temporarily. Proving unsuitable for a lasting settlement, the village was abandoned and all traces of it have disappeared. The name survives, however, in Abercorn Creek, a stream that flows into the Savannah River.

Abercorn was also the name given to a village on the Savannah River. In 1733 ten families were allocated to this settlement and in the following year a number of Salzburgers (German-speaking Protestants from Salzburg in modern-day Austria) settled here temporarily. Proving unsuitable for a lasting settlement, the village was abandoned and all traces of it have disappeared. The name survives, however, in Abercorn Creek, a stream that flows into the Savannah River.

Excerpt from map showing location of the village of Abercorn, 1780s.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Henry Ellis ‘Georgia’s Second Founder’

Described as ‘Georgia’s second founder’ (the first being General Oglethorpe), Henry Ellis served as Governor of the province from 1757 to 1760. He was born into a relatively wealthy family in Monaghan Town, County Monaghan, in 1721. His parents were Francis Ellis and Joan Maxwell, both from families that had settled in Monaghan in the seventeenth century. The Ellis family was of English origin, while the Maxwells were from Scotland.

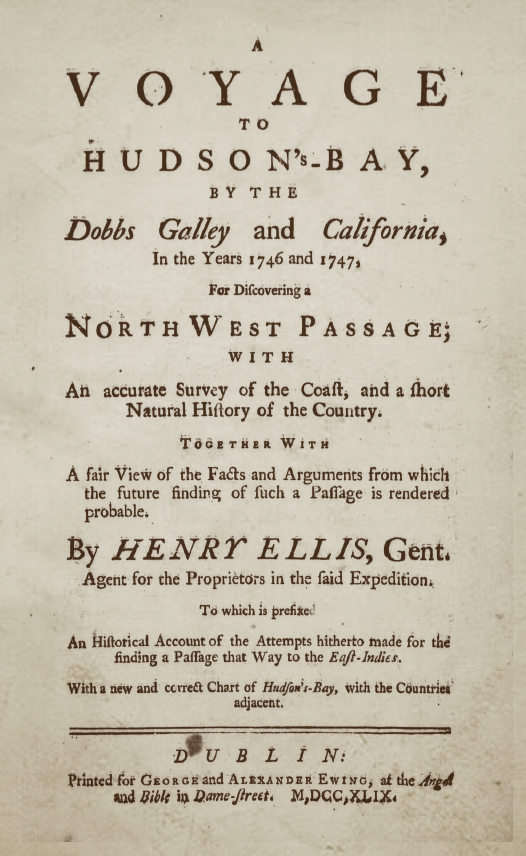

Explorer

As a youth, Ellis went to sea, becoming proficient in navigation and map-making, and in 1746 and 1747 he took part in expeditions to find the ‘Northwest Passage’. He published accounts of these explorations which brought him to the attention of influential figures in government. He was also admitted to the membership of the prestigious scientific institution, the Royal Society.

As a youth, Ellis went to sea, becoming proficient in navigation and map-making, and in 1746 and 1747 he took part in expeditions to find the ‘Northwest Passage’. He published accounts of these explorations which brought him to the attention of influential figures in government. He was also admitted to the membership of the prestigious scientific institution, the Royal Society.

Effective Administrator

Though he spent less than four years in Georgia, Ellis is considered to have been the most capable of the province’s three Royal Governors. As governor, he reorganized local government in Georgia and worked to remove the factionalism that had blighted the colony’s administration. He also faced the challenge of leading the province during the turbulence of the French and Indian War fought by Great Britain and France.

Though he spent less than four years in Georgia, Ellis is considered to have been the most capable of the province’s three Royal Governors. As governor, he reorganized local government in Georgia and worked to remove the factionalism that had blighted the colony’s administration. He also faced the challenge of leading the province during the turbulence of the French and Indian War fought by Great Britain and France.

Later Life

For health reasons Ellis left Georgia in the autumn of 1760. On his return to England he continued to play an influential role in shaping colonial administration. He retired from public service in 1768 and spent much of the rest of his life in Continental Europe. He died unmarried in Italy in 1806. Under the terms of his will he left £3,000 to the hospital in Monaghan Town and another £3,000 to the poor of County Monaghan.

For health reasons Ellis left Georgia in the autumn of 1760. On his return to England he continued to play an influential role in shaping colonial administration. He retired from public service in 1768 and spent much of the rest of his life in Continental Europe. He died unmarried in Italy in 1806. Under the terms of his will he left £3,000 to the hospital in Monaghan Town and another £3,000 to the poor of County Monaghan.

Title page of Henry Ellis’s 1749 book on the search for the ‘Northwest Passage’.

A plan of the inlets & rivers of Savannah & Warsaw in the Province of Georgia, 1751. Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

A plan of Savannah, 1761, showing the layout of streets and squares including ‘Ellis’s Square’. Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

John Rae of County Down And Savannah

John Rae was the son of a Presbyterian tenant farmer from near the small town of Ballynahinch in County Down. In the 1730s he emigrated to America. Moving to what was then the Georgia frontier, he became a successful merchant, trading with the Cherokees and Creeks, and had his own private fort near Augusta.

Move to Savannah

Some years later Rae withdrew to the environs of Savannah and bought a plantation to which he gave the name Rae’s Hall. This lay alongside the Savannah River and ocean-going vessels were able to sail to it. He took part in public life as a justice of the peace and as a member of the Georgia Assembly. In 1765 he wrote that Savannah was ‘the Capital Town of the Province, and it grows very fast, and will soon be a great Place of Trade’.

Some years later Rae withdrew to the environs of Savannah and bought a plantation to which he gave the name Rae’s Hall. This lay alongside the Savannah River and ocean-going vessels were able to sail to it. He took part in public life as a justice of the peace and as a member of the Georgia Assembly. In 1765 he wrote that Savannah was ‘the Capital Town of the Province, and it grows very fast, and will soon be a great Place of Trade’.

Ambitious Emigration Scheme

In 1764–5 Rae and another Ulsterman, George Galphin from County Armagh, embarked on an ambitious project to bring large numbers of families from Ulster to Georgia. They secured a vast tract of land alongside the Ogeechee River from the Governor and Council of Georgia. Rae believed that families would be attracted to Georgia where, unlike in Ireland, there were no rents to be paid to landlords and no tithes to the Established Church (the episcopalian Church of Ireland).

In 1764–5 Rae and another Ulsterman, George Galphin from County Armagh, embarked on an ambitious project to bring large numbers of families from Ulster to Georgia. They secured a vast tract of land alongside the Ogeechee River from the Governor and Council of Georgia. Rae believed that families would be attracted to Georgia where, unlike in Ireland, there were no rents to be paid to landlords and no tithes to the Established Church (the episcopalian Church of Ireland).

Queensborough

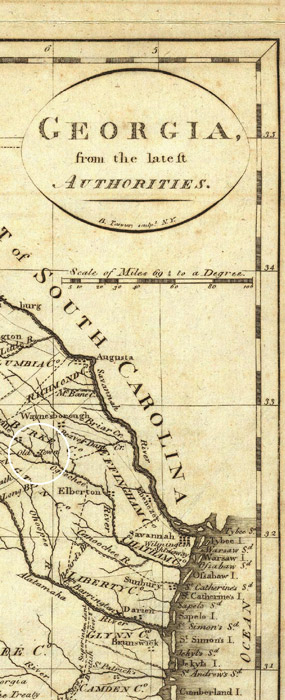

Back in County Down, Rae’s brother Matthew was active in recruiting families for this colonization project. A settlement for the Ulster families was established at Queensborough, around 80 miles northwest of Savannah. However, for a variety of reasons the scheme did not prove to be a great success. Fewer families than expected settled at Queensborough. In addition, conflict between the settlers and the Native Americans and divided loyalties during the Revolutionary War contributed to the demise of the settlement.

Back in County Down, Rae’s brother Matthew was active in recruiting families for this colonization project. A settlement for the Ulster families was established at Queensborough, around 80 miles northwest of Savannah. However, for a variety of reasons the scheme did not prove to be a great success. Fewer families than expected settled at Queensborough. In addition, conflict between the settlers and the Native Americans and divided loyalties during the Revolutionary War contributed to the demise of the settlement.

John Rae’s daughter Elizabeth who married Samuel Elbert, a Revolutionary War hero and Governor of Georgia in 1785–6.

George Galphin’s daughter, Martha, also married a Governor of Georgia: John Milledge (1802–06).

Courtesy Richard Elbert Whitehead

Map of Georgia showing Old Town, 1796, the location of George Galphin’s trading post, cow pens and plantation, which were near the Ulster settlement at Queensborough. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

Immigrants to The Port of Savannah

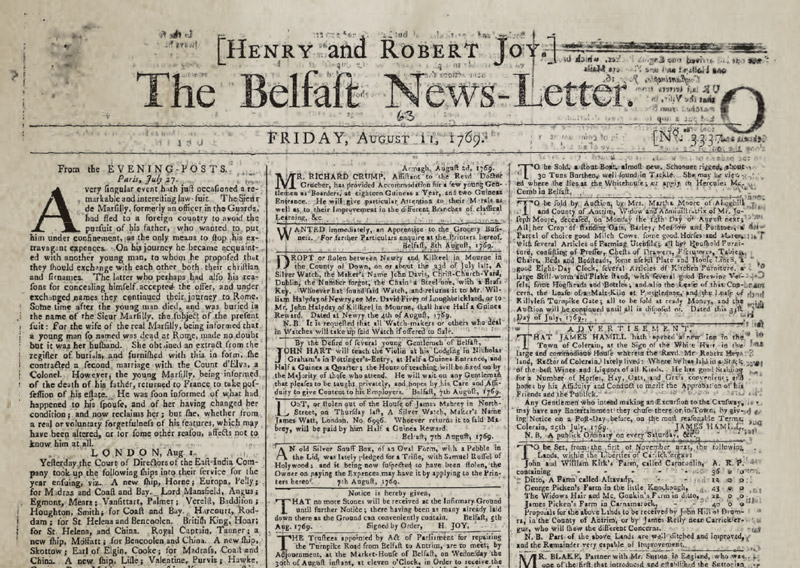

By the late 1760s ships were sailing regularly from ports in Ulster to Savannah, with many of those on board heading to the settlement at Queensborough. Occasionally a ship’s passengers published a declaration paying tribute to their captain for his good conduct towards them. Published in the Belfast Newsletter of 13 March 1772 was one such declaration.

Passengers on The Britannia

The passengers on the Britannia that sailed from Belfast to Savannah issued a statement on 18 January 1772 in which they expressed their appreciation of Captain Clendinnen for ‘the generous and humane manner in which he treated every individual, and particularly for the generous and tender care he took of every sick person on board his ship.’ The names of the passengers were as follows:

|

Anderson, John |

Gillmore, John |

Miller, Robt |

|

Advertisement from the Belfast Newsletter of 11 Aug. 1769 concerning the settlement at Queensborough, Georgia

Sketch of the northern frontiers of Georgia, extending from the mouth of the River Savannah to the town of Augusta, 1780, showing the location of John Rae’s plantation. Courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

The Wylly Family of Coleraine and Savannah

Around the middle of the eighteenth century, William Wylly, an innkeeper and linen draper from Coleraine, County Londonderry, emigrated to the Leeward Islands in the West Indies. Several of his sons accompanied him. In the early 1750s one of William’s sons, Alexander, moved to Georgia where he established a trading business and practised law. In 1763 he acquired a plantation near Savannah to which he gave the name Colerain after his home in Ulster.

American Revolution

Alexander served as Speaker of the Commons House of Assembly from 1763 to 1768. In 1773 he became the clerk of Governor James Wright’s Council. He was a loyalist during the Revolutionary War and fled to East Florida in 1776. He returned to Savannah in 1778, helping to defend the city during the siege of 1779, and remained there until his death in late 1780 or early 1781.

Alexander served as Speaker of the Commons House of Assembly from 1763 to 1768. In 1773 he became the clerk of Governor James Wright’s Council. He was a loyalist during the Revolutionary War and fled to East Florida in 1776. He returned to Savannah in 1778, helping to defend the city during the siege of 1779, and remained there until his death in late 1780 or early 1781.

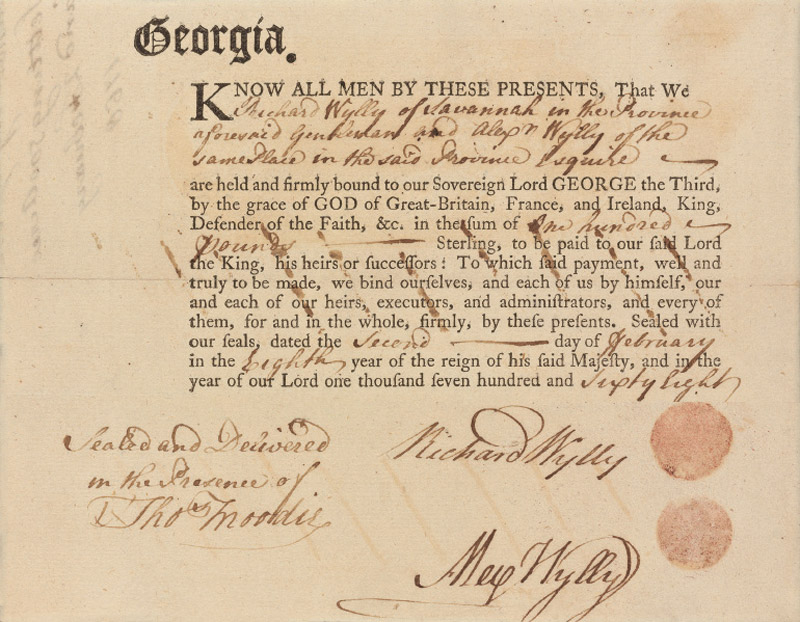

Richard Wylly

Unlike his brother Alexander, Richard Wylly took the side of the Patriots in the Revolutionary War. From the late 1760s he had been operating as a merchant in Savannah, trading in a broad range of commodities including rum, sugar, coffee and chocolate. During the Revolutionary War, he was a colonel in command of a Georgia brigade and in 1779 was the Deputy Quarter Master General in General Lincoln’s army. His nephew, Thomas Wylly, served as his assistant quarter master.

Unlike his brother Alexander, Richard Wylly took the side of the Patriots in the Revolutionary War. From the late 1760s he had been operating as a merchant in Savannah, trading in a broad range of commodities including rum, sugar, coffee and chocolate. During the Revolutionary War, he was a colonel in command of a Georgia brigade and in 1779 was the Deputy Quarter Master General in General Lincoln’s army. His nephew, Thomas Wylly, served as his assistant quarter master.

‘A Gentleman of Character’

Captured by the British, Richard Wylly spent some time as a prisoner before being released. In 1782 he was described by John Martin, the Governor of Georgia, as ‘a gentleman of character and one who is much esteemed by his fellow citizens’. Richard Wylly died at his home near Savannah in 1801. He was buried in Colonial Park Cemetery in one of a series of brick vaults known as the ‘Colonial vaults’.

Captured by the British, Richard Wylly spent some time as a prisoner before being released. In 1782 he was described by John Martin, the Governor of Georgia, as ‘a gentleman of character and one who is much esteemed by his fellow citizens’. Richard Wylly died at his home near Savannah in 1801. He was buried in Colonial Park Cemetery in one of a series of brick vaults known as the ‘Colonial vaults’.

Richard Wylly’s vault (far left) in Colonial Park Cemetery, Savannah. Courtesy Carol M. Highsmith’s America Project in the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Obligation of Richard Wylly and Alexander Wylly of Savannah, to the King, for £100, 1768. Courtesy New York Public Library.

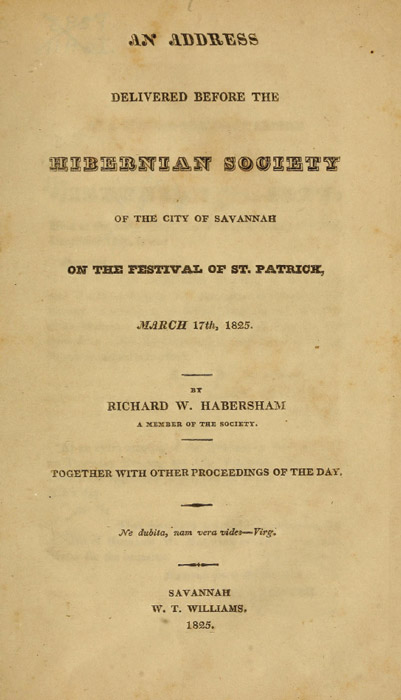

An address delivered before the Hibernian society of the city of Savannah on the festival of St. Patrick, 1825. The author Richard Wylly Habersham was a nephew of Alexander and Richard Wylly.

French map of the siege of Savannah, 1779. Courtesy Library of Congress, Map Division.

Dr John Cumming and the Hibernian Society

John Cumming was born near the town of Ballymena in County Antrim in 1768. Following a move to America, he began to study medicine with a relative in Baltimore before continuing his education in Edinburgh, which was famed for the high standard of its medical school. On returning to America he lived for a time in Augusta before moving to Savannah.

Life in Savannah

Though often referred to as ‘Dr Cumming’, he seems to have been primarily a merchant and factor in Savannah. He was active in many other areas of city life. Soon after settling in Savannah Cumming was instrumental in the creation of the Savannah Volunteer Guard and was the force’s first commander. He was one of the founders of the Georgia Medical Society and was a member of the Independent Presbyterian Church in Savannah, where he held the office of elder. He also served as President of the Savannah Branch of the United States Bank.

Though often referred to as ‘Dr Cumming’, he seems to have been primarily a merchant and factor in Savannah. He was active in many other areas of city life. Soon after settling in Savannah Cumming was instrumental in the creation of the Savannah Volunteer Guard and was the force’s first commander. He was one of the founders of the Georgia Medical Society and was a member of the Independent Presbyterian Church in Savannah, where he held the office of elder. He also served as President of the Savannah Branch of the United States Bank.

Hibernian Society of Savannah

In 1812 Cumming was one of the founders of the Hibernian Society of Savannah and was the original President of the Society, serving from 1812 to 1815. Cumming was one of a number of individuals with roots in Ulster to play an active part in forming the Society. The second president, Moses Cleland, was possibly from County Down. Another of the founders was David Bell from County Down, who was the last survivor of the original members

In 1812 Cumming was one of the founders of the Hibernian Society of Savannah and was the original President of the Society, serving from 1812 to 1815. Cumming was one of a number of individuals with roots in Ulster to play an active part in forming the Society. The second president, Moses Cleland, was possibly from County Down. Another of the founders was David Bell from County Down, who was the last survivor of the original members

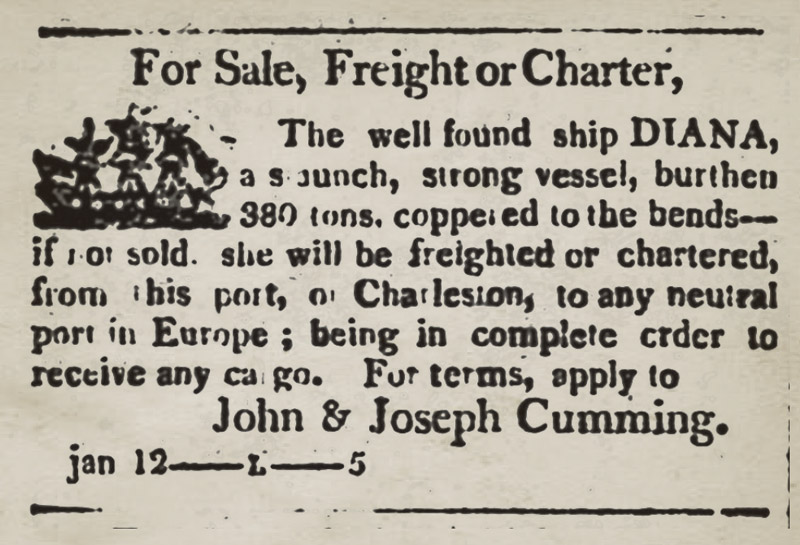

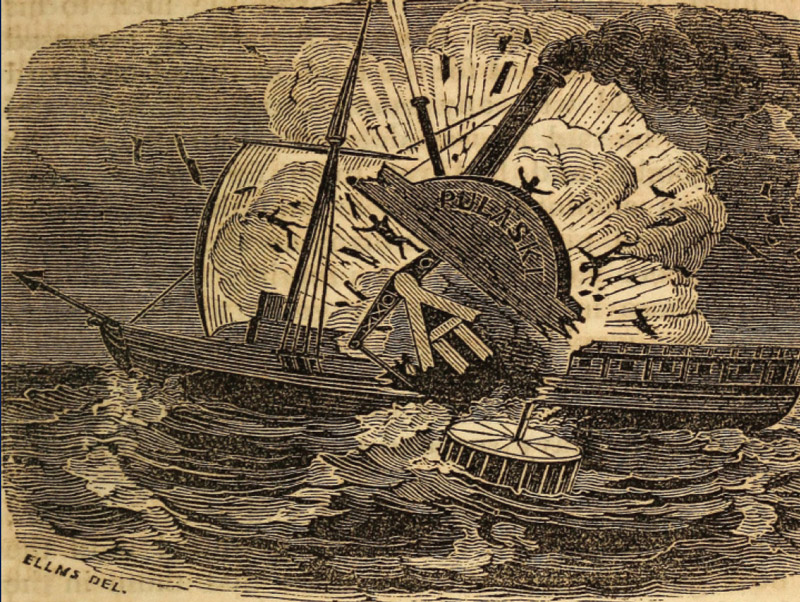

Death at Sea

In June 1838 Cumming and his wife Susanna perished when the steamship Pulaski, on which they were travelling to Baltimore, sank following an on-board explosion. Warm tributes were paid to him by the members of the Hibernian Society among others. The President of the Society at the time of his death was his son George B. Cumming who held this office for nearly a quarter of a century, from 1832 to 1856.

“... it becomes the duty of their more fortunate brethren settled in this free country, and enjoying the benefits of its hospitality, to reach out the hand of friendship, to tender the aid of a delicate charity, and to offer any other assistance which fraternal, manly, and kindly feelings may inspire.”

Extract from the preamble of the Hibernian Society’s charter, adopted 17 March 1812

In June 1838 Cumming and his wife Susanna perished when the steamship Pulaski, on which they were travelling to Baltimore, sank following an on-board explosion. Warm tributes were paid to him by the members of the Hibernian Society among others. The President of the Society at the time of his death was his son George B. Cumming who held this office for nearly a quarter of a century, from 1832 to 1856.

“... it becomes the duty of their more fortunate brethren settled in this free country, and enjoying the benefits of its hospitality, to reach out the hand of friendship, to tender the aid of a delicate charity, and to offer any other assistance which fraternal, manly, and kindly feelings may inspire.”

Extract from the preamble of the Hibernian Society’s charter, adopted 17 March 1812

The Republican; and Savannah Evening Ledger, 16 Jan. 1813. Joseph Cumming was Dr John Cumming’s son.

The explosion on the steamship Pulaski in 1838. From The Tragedy of the Seas by Charles Elms (1848).

The Independent Presbyterian Church, Savannah. Courtesy Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

The Hunter Family of County Donegal and Savannah

Three Hunter brothers, William, James and Alexander, were prominent in business in Savannah in the early nineteenth century. Two of their sisters, Isabella and Lydia Elizabeth, also joined them there. They were the children of Col. John Hunter, an army officer from Letterkenny in County Donegal. It was claimed that this family was descended from the Hunters of Hunterston in Scotland.

William Hunter

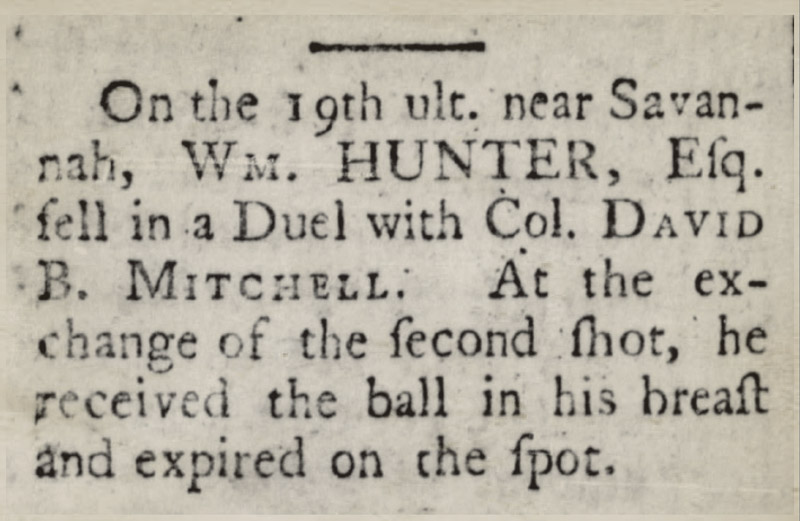

At the beginning of the nineteenth century William Hunter was one of Savannah’s leading merchants. He was a director of the Bank of Discount and Deposit and was the Navy Agent for Georgia. In August 1802 Hunter fought a duel with Scottish-born David B. Mitchell, who had recently completed his term as mayor of Savannah. Tensions between the two men had been rising over the previous months due to their political differences. In the duel Mitchell’s second shot fatally wounded Hunter.

At the beginning of the nineteenth century William Hunter was one of Savannah’s leading merchants. He was a director of the Bank of Discount and Deposit and was the Navy Agent for Georgia. In August 1802 Hunter fought a duel with Scottish-born David B. Mitchell, who had recently completed his term as mayor of Savannah. Tensions between the two men had been rising over the previous months due to their political differences. In the duel Mitchell’s second shot fatally wounded Hunter.

James Hunter

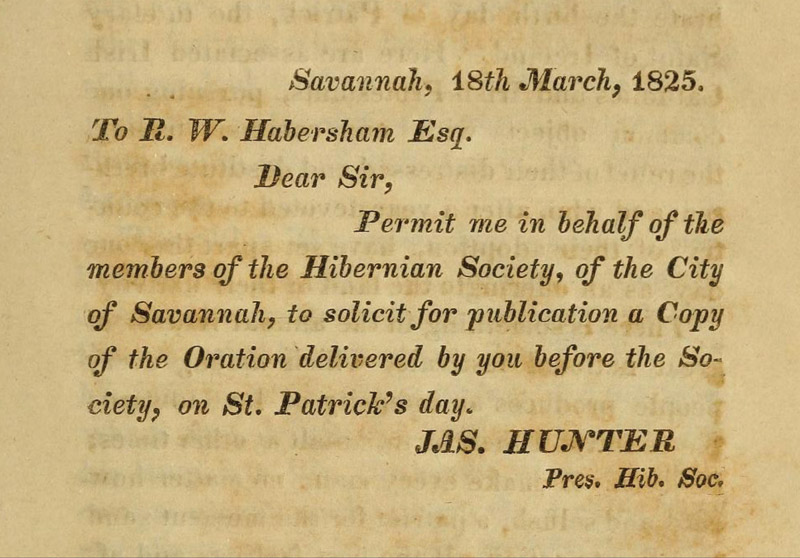

James Hunter continued the business and became one of Savannah’s most respected businessmen in the first half of the 1800s. He served as an alderman and was an active member of the Independent Presbyterian Church. He was one of the founders of the Hibernian Society in Savannah in 1812 and served as President of the Society from 1816 to 1832. It was during his time as President that the Society organised the first public St Patrick’s Day parade in 1824.

James Hunter continued the business and became one of Savannah’s most respected businessmen in the first half of the 1800s. He served as an alderman and was an active member of the Independent Presbyterian Church. He was one of the founders of the Hibernian Society in Savannah in 1812 and served as President of the Society from 1816 to 1832. It was during his time as President that the Society organised the first public St Patrick’s Day parade in 1824.

Alexander Hunter

The third brother, Alexander, was also involved in the commercial life of the city and for a time was surveyor of the port of Savannah. He died in 1827 and his death notice in the Savannah Republican stated that he was a native of Donegal and had been in Savannah for 24 years. He was secretary of the Hibernian Society at the time of his death and the members agreed to wear mourning crepe on their left arm for 30 days in his memory.

The third brother, Alexander, was also involved in the commercial life of the city and for a time was surveyor of the port of Savannah. He died in 1827 and his death notice in the Savannah Republican stated that he was a native of Donegal and had been in Savannah for 24 years. He was secretary of the Hibernian Society at the time of his death and the members agreed to wear mourning crepe on their left arm for 30 days in his memory.

Louisville Gazette, 1 Sept. 1802.

From An address delivered before the Hibernian society of the city of Savannah on the festival of St. Patrick, 1825.

Savannah Georgian, 15 March 1825.

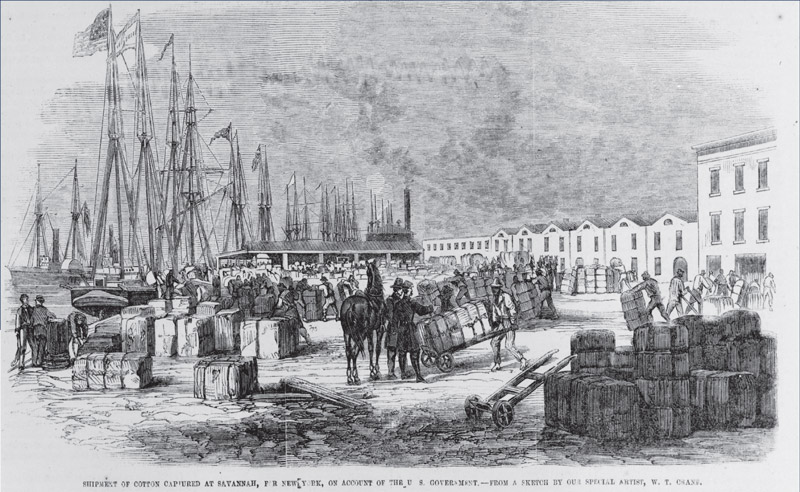

Shipment of cotton at Savannah, 1865. Courtesy Library of Congres

Some Other Ulster Connections with Savannah

Georgia’s First Historian

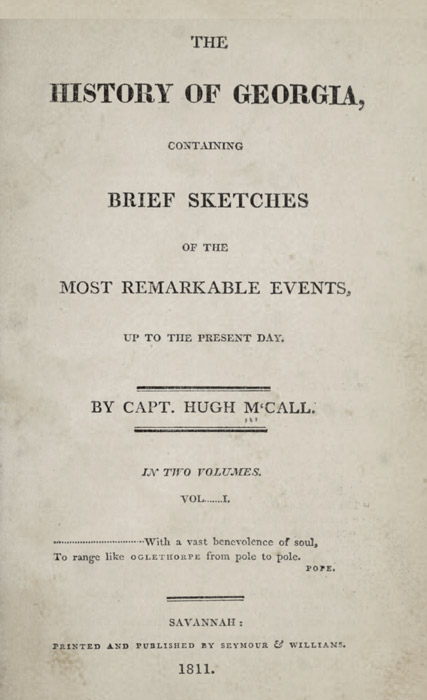

Hugh McCall is generally considered to be the first historian of Georgia. The first volume of his work, The History of Georgia: Containing Brief Sketches of the Most Remarkable Events, Up to the Present Day, was published in Savannah in 1811, with the second volume following five years later. McCall was of Scotch-Irish heritage and his father, Col. James McCall, had been a prominent figure in the Revolutionary War. Hugh McCall served as an officer in the United States Army and also held the position of jailer in Savannah. He died in 1823 and was buried in Colonial Park Cemetery.

Hugh McCall is generally considered to be the first historian of Georgia. The first volume of his work, The History of Georgia: Containing Brief Sketches of the Most Remarkable Events, Up to the Present Day, was published in Savannah in 1811, with the second volume following five years later. McCall was of Scotch-Irish heritage and his father, Col. James McCall, had been a prominent figure in the Revolutionary War. Hugh McCall served as an officer in the United States Army and also held the position of jailer in Savannah. He died in 1823 and was buried in Colonial Park Cemetery.

“The family of which I am descended were Scots, and in Scotland lived in the neighborhood of Calhoun, properly Colquhoun. The time of their migration is not known, but McCalls, Harrises and Calhouns passed over from Scotland in the same ship to the northeast of Ireland where they settled and remained two entire generations. Then the three families migrated to Pennsylvania …”

Thomas McCall, brother of Hugh McCall, writing in 1829

James Magee in Savannah

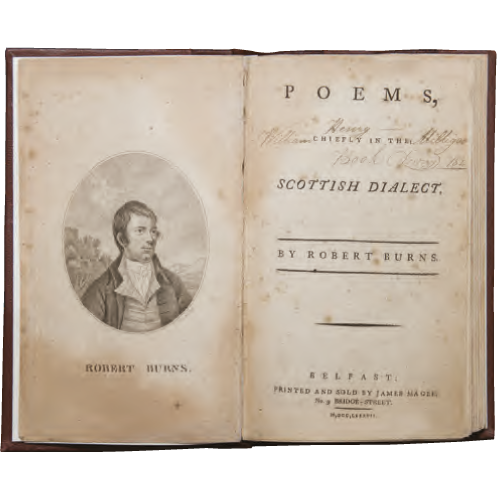

James Magee came from a family of printers and publishers in Belfast. In 1787 his grandfather James published an edition of Robert Burns’s first book of poetry. The younger James emigrated to America and by the early 1820s had set himself up as a merchant in Savannah, trading in rum and Irish linen. It is said that he made and lost a fortune in Savannah. Later he moved to Mobile, Alabama, where he again enjoyed success in business. One story told about him is that he invited all those to whom he owed money to a banquet and wrapped what was due to each of them in their dinner napkins. During the American Civil War, he was British Consul in Mobile.

James Magee came from a family of printers and publishers in Belfast. In 1787 his grandfather James published an edition of Robert Burns’s first book of poetry. The younger James emigrated to America and by the early 1820s had set himself up as a merchant in Savannah, trading in rum and Irish linen. It is said that he made and lost a fortune in Savannah. Later he moved to Mobile, Alabama, where he again enjoyed success in business. One story told about him is that he invited all those to whom he owed money to a banquet and wrapped what was due to each of them in their dinner napkins. During the American Civil War, he was British Consul in Mobile.

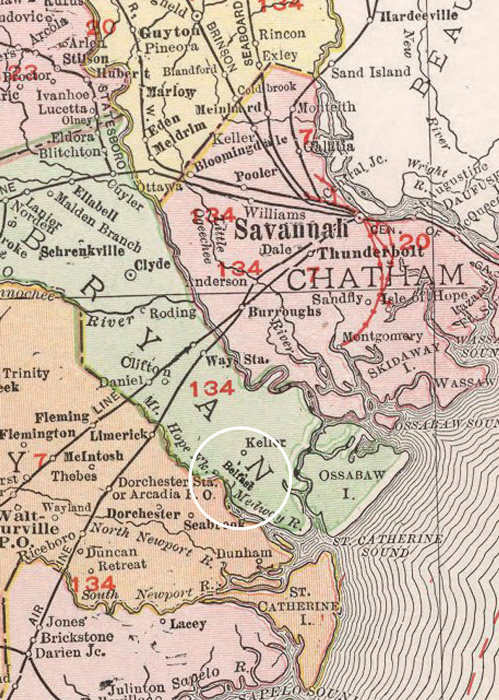

The Library Atlas of the World (1912), showing the location of Belfast, Bryan County, GA. Courtesy David Rumsey Map Collection.

The History of Georgia: Containing Brief Sketches of the Most Remarkable Events, Up to the Present Day

Title page of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect by Robert Burns, published in Belfast by James Magee.