Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents

From Ulster to America - Stories of the Scotch-Irish

Over the centuries, many hundreds of thousands of Ulster-Scots (also known as the Scotch-Irish or Scots-Irish) have left these shores. Today, thousands of people return to this island every year in search of their Ulster-Scots roots.

Here we tell the stories of a number of Ulster-Scots individuals and families in America and the great diversity of their experiences. You will discover at first hand the stories of some of those who left these shores to begin a new life on the other side of the Atlantic.

The Scotch-Irish are the bedrock of the United States. Their deeds have shaped the nation, from the Declaration of Independence to the moon landings and beyond. They have provided leadership out of all proportion to their numbers, whether as politicians, soldiers, business people, inventors or clergy. Seventeen out of forty-four Presidents of the United States could claim Scotch-Irish roots.

The contribution of the Scotch-Irish goes far beyond famous deeds and famous people, however. It is their character and ideals, especially their love of freedom, that have had the greatest impact for they have literally defined what it is to be an American.

It must be remembered, however, that the fundamental character of the Scotch-Irish was forged not in America, but in Ulster (where they are known as Ulster-Scots). The people who secured the frontiers of the American Colonies had first secured the frontiers of Ulster. The people who denied the right of a King to levy taxes without representation had already denied the right of a King to tell them how to worship. The people who refused to surrender at the Alamo were the same people whose cry was “No Surrender” when they held out against the odds at the great siege of Londonderry in 1689. The people who pushed ever westward, opening up the American continent, had first sailed west from Scotland to Ulster and then from Ulster to America.

Ulster-Scots, Scotch-Irish and Scots-Irish

Three Names, One People

From the early 1600s onwards Lowland Scots came to Ulster in their thousands seeking prosperity and religious freedom. Today in Ulster, their descendants and the hundreds of thousands who came after them are known as Ulster-Scots.

Over the centuries, however, religious persecution and economic woes encouraged many Ulster-Scots to head westward in search of prosperity, to the American colonies and later the United States of America. In America, those Ulster-Scots and their descendants, who now number up to 20 million people, are known as the Scotch-Irish (or sometimes Scots-Irish). Put simply, Ulster-Scots and Scotch-Irish are two names for the same people: in Ulster, the Ulster-Scots and in America, the Scotch-Irish.

Both names have been in use for well over 300 years. One of the earliest recorded instances of the term Ulster-Scot in relation to Ireland dates back to the 1640s, while the term Scotch-Irish has been in use in America since at least the 1690s. Sometimes the same term has been used on both sides of the Atlantic. Rev Francis Makemie of Donegal, who would later become known as the Father of American Presbyterianism, studied divinity at Glasgow University. In common with his fellow students from Ulster, his origin in the University records of 1675 was given as “Scoto-Hybernicus” or Scotch-Irish.

In relatively recent times, a number of myths have become erroneously attached to the term Scotch-Irish. The first is that the name was only adopted in the late 1800s as a means to differentiate Protestant migrants from Ireland from the thousands of Catholic Irish who migrated to America during the potato famine of 1845–52. This is obviously false, as the term Scotch-Irish had already been in use for 150 years before the potato famine happened. The second is that the term Scotch relates not to a people, but to an alcoholic beverage. However, this is another mistaken notion, the result of twentieth-century drink marketing. The term Scotch is used in Ulster to describe people from Scotland to this day.

1. From Ulster to America

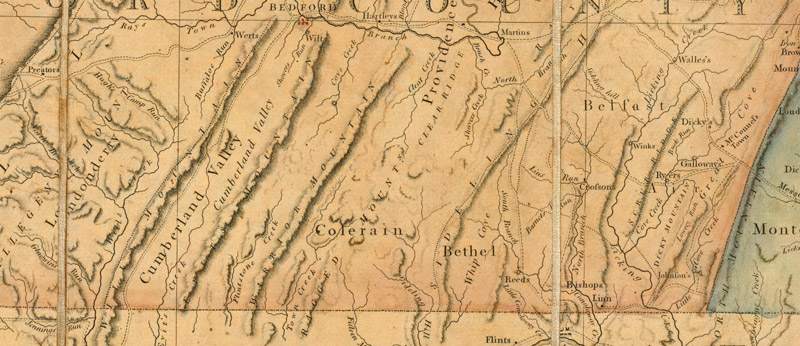

The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World.

By this time significant numbers of families were also moving to Pennsylvania, which would become the main focus of Ulster emigration for decades. In time the settlement of Ulster families became significant in other areas of the Colonies, including Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia. While all religious denominations were represented in the migration stream, Presbyterians were by far the most numerous throughout the 1700s.

If the numbers emigrating from Ulster to America in the 1700s were impressive – perhaps in the region of 120,000 –180,000 – these are dwarfed by the figures for the 19th century when possibly as many as 1.5 million people left the province for North America. While the destination for many of these migrants was Canada, a clear majority ended up in the United States. Emigration in this period was more religiously and culturally diverse and no one grouping dominated the outflow of families. Having said that, proportionately, the transatlantic migration of Ulster-Scots in the 1800s remained hugely significant, while numerically it was far greater than in the previous century.

The factors accounting for emigration from Ulster to America have been numerous and complex. The numbers of people crossing the Atlantic has not been constant, with variations depending on economic conditions in Ireland, for instance, as well as other external factors. Chain migration was hugely significant as emigrants followed the routes taken by family members and neighbours from home who had gone before. The story of the relationship between Ulster and America comes right down to the present as the United States continues to hold out the prospect of opportunities for those ready to seize them.

2. Ulster-Scots and Colonial America

Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, administration and defence of Colonial America.

James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier life, to settle there.

Arthur Dobbs (1689-1765) was a landowner and politician from County Antrim. He purchased 400,000 acres in North Carolina and organised ships to carry hundreds of settlers from Ulster. Writing in 1755, he described them as, “a Colony from Ireland removed from Pennsylvania of what we call Scotch-Irish Presbyterians who with others in the neighbouring Tracts had settled together in order to have…a minister of their own opinion and choice.” Dobbs served as Governor of North Carolina from 1753 to 1765.

Robert Rogers (1731–95) founded an elite military unit, Rogers’ Rangers, during the French and Indian War (1754-63) that is regarded as the forerunner of America’s elite forces. The modern US Army Rangers were ‘activated’ at Carrickfergus, County Antrim, in 1942 and a modified version of Rogers’ 28 Rules for Ranging is still in use today. Rogers’ father named his New Hampshire property Munterloney, after the district his family came from in the Sperrin Mountains of County Tyrone. On 24 April 1778, the USS Ranger, captained by John Paul Jones, scored a historic victory by capturing a British warship, HMS Drake, off the coast of Carrickfergus, County Antrim.

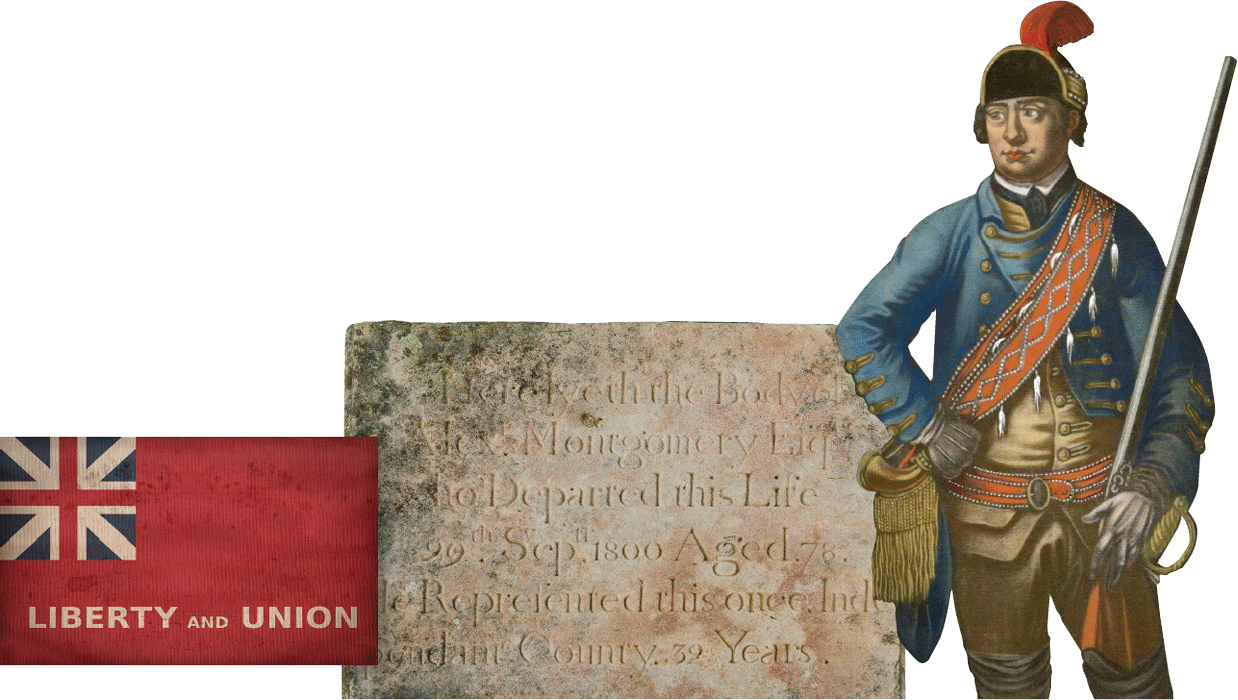

Alexander Montgomery (d. 1800) of Convoy, County Donegal, served as a captain in the 43rd Foot during the French and Indian War. He earned a reputation for ruthlessness and is said to have killed his commanding officer in a duel. He returned to Ireland after the war and in 1768 was elected MP for County Donegal, holding this seat in every subsequent election until his death in 1800. He was a strong supporter of the American colonists, earning him the nickname ‘Americanus’.

3. The Declaration of Independence

The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first statement in the Colonies promising armed resistance to the Crown.

The signatories of the 1776 Declaration of Independence included three men who had been born in Ulster: George Taylor, born in County Antrim, in 1716; James Smith, who emigrated to America as a boy around 1719; and Matthew Thornton, who was born in the Bann Valley straddling counties Antrim and Londonderry, around 1714.

Two other signatories were the sons of Ulster immigrants: Thomas McKean, whose father was from the Ballymoney area of County Antrim; and Edward Rutledge, whose father was from County Tyrone. In addition, John Hancock, whose flowing signature has gone down in history, is believed to have had County Down ancestors.

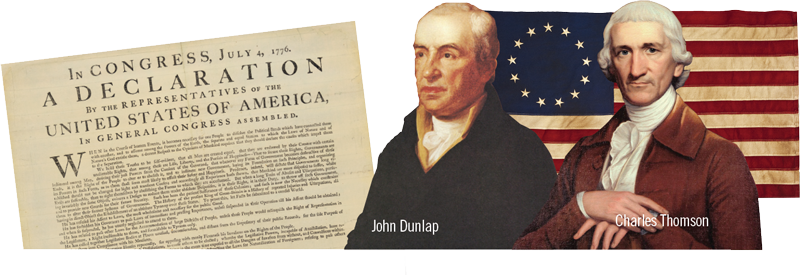

The Declaration of Independence was printed in Philadelphia by John Dunlap (1746–1812) from Strabane, County Tyrone. Aged 10 he had emigrated to Pennsylvania to work as an apprentice printer to his uncle William Dunlap, and in 1766 John took the business over. John founded the Pennsylvania Packet in 1771, which later became America’s first daily newspaper. During this time, he actively encouraged commercial advertising, placing adverts in specific locations on the page and introducing illustrations and engravings to help draw the reader’s eye to the advert.

The printed version of the Declaration of Independence included only two names – those of John Hancock and Charles Thomson (1729–1824). Thomson was born at Upperlands, near Maghera in County Londonderry, and arrived in America in 1739 as an orphan. He went on to become one of Philadelphia’s leading citizens and was Secretary to the Continental Congress throughout its existence from 1774 to 1789. He also designed the Great Seal of the United States.

4. The War of Independence

The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775.

Another Donegal man, also the descendant of a Scottish minister, to make his mark on the War of Independence was Gustavus Conyngham who was the most successful captain in the Continental Navy, capturing 24 ships in one 12-month period alone.

Born near Newtownstewart, County Tyrone, William Maxwell emigrated to America with his father in the 1740s and settled in New Jersey. During the War of Independence, he served with distinction and rose to the rank of brigadier general. Because of his ancestry and accent, he was known to his men as ‘Scotch Willie’.

Two of George Washington’s closest associates during the war were Henry Knox and James McHenry. Knox, the son of an immigrant from Londonderry, became one of the most senior officers in the Continental Army – in fact, the most senior officer for a 6-month period in 1783–4 – and was the first Secretary of War in the new United States. Knoxville, Tennessee, was one of several towns named in his honour, as was Fort Knox in Kentucky. Born in Ballymena, McHenry emigrated to America just a few years before the outbreak of the War of Independence. He became secretary and aide to George Washington in 1778. In 1796 he too was appointed Secretary of War. Fort McHenry in Baltimore was named for him.

The divided loyalties of some Ulster-Scots during the War of Independence are reflected in the life of Alexander Chesney (1755–1843). Born near Ballymena, he emigrated to America in 1772 and settled in South Carolina. From 1776 to 1779 he fought for the Patriot cause. However, in 1780 he switched sides and fought for the British until 1782, after which he returned to Ireland and lived most of the rest of his long life at Annalong, County Down.

5. First-Generation Presidents

Only four first-generation Americans have been President of the United States. The first three were the sons of Ulster-born fathers (two had Ulster-born mothers), and the fourth, Barack Obama, claims Scotch-Irish descent through his grandparents.

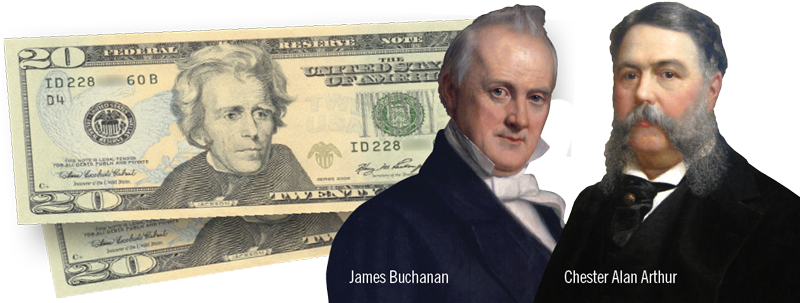

The parents of Andrew Jackson (1767–1845) left Boneybefore, near Carrickfergus, in 1765, emigrating to America. Jackson’s father died shortly before he was born in 1767 and he was raised in modest circumstances in the Waxhaws, on the border between North and South Carolina. He went on to become a successful lawyer and businessman in Nashville, Tennessee, and was a celebrated war hero, defeating the British at New Orleans in 1815. He served as President from 1829 to 1837, and was the first holder of that office not to have come from a privileged background. Though a highly controversial figure, not least because of his treatment of Native Americans, his impact on America was such that the period of his presidency and many years after it was known as the ‘Age of Jackson’.

The father of James Buchanan (1791–1868), James Buchanan senior, was born at Low Cairn, Ramelton, County Donegal, in 1761. He was raised at Stony Batter, a few miles from Ramelton, on the farm that was owned by his mother’s family, the Russells. The homestead still stands, though is in ruins. James Buchanan senior emigrated to America in 1783 and his son, the future president, was born in 1791 at the property in Pennsylvania that he called Stony Batter after his Donegal home. Buchanan was President on the eve of the Civil War. It is said that he once remarked, ‘My Ulster blood is my most priceless heritage’.

In 1815 the father of Chester A. Arthur (1829–86) left Dreen, Cullybackey, County Antrim, for America. Born in Vermont and raised in New York state, he was elected Vice-President in 1880. Following the assassination of President Garfield in 1881, he succeeded to the presidency. On 4 July 1884 a ‘Scotch- Irish Presbyterian Reunion’ was held in St Enoch’s Church in Belfast. During the reunion a message was sent to President Arthur extending to him the good wishes of those gathered. In reply Arthur wrote, ‘Coming from kindred ancestry the kind greetings of the Scotch-Irish assembled at Belfast today are especially pleasing, and are very cordially reciprocated.’

6. Other Presidents

One of the most highly regarded Presidents, Woodrow Wilson was born in the Presbyterian manse in Staunton, Virginia, and grew up very conscious of his Scotch-Irish ancestry. He once said, ‘The stern Covenanter tradition that is behind me sends many an echo down the years.’ On another occasion, with some humour, he remarked, ‘No-one who amounts to anything is without some Scotch-Irish blood.’ His grandfather is thought to have been from Dergalt, near Strabane.

Though much happier as a soldier than a politician, Ulysses Simpson Grant followed the path of many a war hero in becoming President, serving from 1869 to 1877. Grant’s Irish ancestry was through his maternal line. The Simpson family farmed for generations at Dergenagh, near Ballygawley, County Tyrone.

Vice-President to Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Johnson succeeded the assassinated president in 1865. His ancestors are said to have been from the Mounthill/Raloo area of County Antrim. The last Civil War veteran to serve as president, William McKinley’s ancestors emigrated from Conagher, near Ballymoney, County Antrim, around 1743. He was assassinated in 1901 in the first year of his second presidential term. He was succeeded by Theodore Roosevelt whose ancestors are said to have been Irvines, Craigs and Bullochs from Gleno area of County Antrim. Richard Nixon had several lines of Ulster ancestry and his Millhouse forebears are believed to have lived in Carrickfergus for a time. An 18th-century ancestor of Jimmy Carter, Andrew Cowan, was possibly from County Antrim, while George Bush also had an 18th-century ancestor, William Gault, possibly from the same county. Bill Clinton claimed to have Cassidy ancestors from County Fermanagh. While visiting Belfast in 1995, Clinton declared: ‘I am proud to be of Ulster-Scots stock’.

Several other presidents have Ulster roots, though it has not been possible to identify a specific location in Ulster for their forebears. The ancestors of James K. Polk may have been from County Londonderry and emigrated to America in the early 18th century. Grover Cleveland’s maternal grandfather, Abner Neal, emigrated from County Antrim in late 1700s. Benjamin Harrison also had forebears of Ulster ancestry (Irwins and McDowells).

7. Pioneers and Adventurers

Families of Ulster birth or descent contributed to the westward expansion of America. At the birth of the new United States they were one of the dominant groups in the interior of the new Republic. Famous pioneers such as Davy Crockett, Sam Houston, Jim Bowie and Daniel Boone were all of Ulster-Scots descent.

While most farmed, some worked as fur traders, such as James Adair (d. 1783), who is believed to have been from County Antrim. In 1775 he published, The History of the American Indians, in which he demonstrated a keen awareness of the Native American way of life. The recent film, The Revenant, is based on an incident in the life of Hugh Glass (d. 1833), a Scotch-Irish fur trader and explorer. William Clark of the famous Lewis and Clark expedition that began in 1804 was Scotch-Irish, as were some of the others on the expedition.

The contribution of Ulster-Scots to the founding and development of new towns and settlements can be observed at numerous locations in America. Taking Nashville, Tennessee, as an example, both of the men credited with founding the modern city, James Robertson and John Donelson, are reputed to have sprung from families originating in east County Antrim. According to one source, Donelson was from the Carnmoney area. Robertson’s Antrim associations are less certain. However, it is clear from what we know of the earliest inhabitants of Nashville that there was a very strong Scotch-Irish element to the population and businessmen with Ulster connections contributed greatly to its development.

Bringing the story up to more recent times, Ulster-Scots pioneers have made it as far as the moon. Colonel James B. Irwin flew on the Apollo 15 mission in 1971. This fourth manned lunar mission was distinguished by the first utilisation of the famous lunar rover. Irwin’s grandparents came from Altmore and Turnabarson, Pomeroy, County Tyrone. In September 1979 Col. Irwin travelled to Northern Ireland to make a personal visit his ancestral home.

8. Presbyterians and Preachers

The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to religious life in America, especially across the various strands of Presbyterianism, has been immense. As far as Presbyterianism is concerned, it could be argued that settlers from Ulster made the key contribution. The distribution of Presbyterian churches has even been used as an indicator of westward expansion.

Donegal-born Francis Makemie emigrated to Maryland in 1683. In 1706, he was instrumental in founding the first presbytery in America and has become known as the ‘Father of American Presbyterianism’. Presbyterian ministers from Ulster made a significant contribution to the movement of Ulster-Scots families to America. As the natural leaders of their communities, they were often the drivers of emigration. Examples include Rev. James McGregor of Aghadowey, County Londonderry, in 1718, Rev. Thomas Clark, minister of Cahans Presbyterian Church, County Monaghan, in 1764 and the Covenanter Rev. William Martin, who led large numbers of Covenanter families to South Carolina in 1772.

The migration of ministers from Ulster to America continued in the 19th and 20th centuries. Rev. Thomas Campbell (1763–1854), was minister of Ahorey in County Armagh, before emigrating to America and founding what became the Disciples of Christ denomination. Rev. Dr John Hall (1829–98), who was born in Ballygorman, Loughgilly parish, County Armagh, served the Presbyterian Church in Ireland for more than a decade (in the cities of Armagh and Dublin), before, in 1867, becoming minister of Fifth Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York City. In 1889 he was one of the founders of the Scotch-Irish Society of America.

Over the centuries Scotch-Irish people became Baptists, Methodists and other denominations and made a great contribution to all of them, and still do to this day.

9. Schools, Colleges and Universities

Educational establishments across America owe their origins to Ulster-Scots. The College of New Jersey was founded in 1746 by Presbyterians who wanted to train ministers dedicated to their views. The college has been called the educational and religious capital of Scotch-Irish America. It 1896 it was renamed Princeton University.

Princeton’s origins have been traced to the ‘Log College’ which was founded at Neshaminy, Pennsylvania, by Rev. William Tennent. A native of Linlithgowshire, Scotland, Tennent had moved to Ulster and married a daughter of Rev. Gilbert Kennedy of Dundonald, County Down, before emigrating to America in the 1710s.

In 1761 Rev. Samuel Finley from County Armagh became principal of the College of New Jersey. He was awarded an honorary doctorate by Glasgow University, the first Presbyterian minister in America to be acknowledged in this way by a European university. His great-grandson was the inventor Samuel Morse.

Francis Alison (1705–79) was born into a Presbyterian family near Letterkenny, County Donegal. He received his higher education in Scotland, and was deeply influenced by the views of Francis Hutcheson, an Ulster-Scot from Saintfield, County Down, who held the Chair of Moral Philosophy at Glasgow University. Alison emigrated to America in 1735 where he was ordained a Presbyterian minister. He was also as an excellent teacher and has been called the ‘greatest classical scholar in America’. Among his pupils was Charles Thomson, the future Secretary of the Continental Congress. Alison’s ideas are regarded as having a profound influence on political thought in America.

In 1861 William Barton Rogers, the son of Omagh parents, founded Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 1889 Agnes Scott College was founded in Georgia, named after a Newry woman. The Scotch-Irish also pioneered education for African Americans. Rev Joseph McKee from Anahilt founded what would become Fisk University in Nashville, while Rev John G. Fee founded Berea College in Kentucky.

10. Reformers and Philanthropists

Within the ranks of America’s leading philanthropists were a number of Ulster-Scots. Among those who made an outstanding contribution to the betterment of their fellow citizens was Ezekiel Donnell, born at Ballee, Strabane, County Tyrone, in 1822. Donnell initially settled in Alabama before moving to New York and was a hugely successful cotton merchant. A strong believer in the importance of education, he gave $1m towards the building of a library in New York, which would be open to the public, free of charge.

Samuel Robinson (1865–1958) was born near Cloughmills, County Antrim, and emigrated to Philadelphia in 1888, going into the grocery business. He went on to become president of the American Stores Co., formed in 1917, which was reckoned to be the largest food retailer in the world. Robinson used his vast wealth to support a broad range of causes. These included scholarships for Presbyterians to attend academic institutions with Presbyterian associations. He provided the funds to construct and equip a hospital in Ballymoney – the Robinson Memorial Hospital, which opened in 1933 and was named in memory of his parents.

While it would be wrong to give the impression that Ulster-Scots were uniformly hostile to slavery – many of them did own slaves – it is true that Ulster-Scots were frequently to the fore in antislavery movements. For example, the Reformed Presbyterian Church in the United States, which was largely drawn from Ulster settlers, maintained a consistent line that no slaveholder could be a member of the denomination. Many members of this Church were involved in the Underground Railroad which helped runaway slaves escape to Canada, including Rev. Armour McFarland, a native of Plumbridge in County Tyrone, who sheltered fugitive slaves in a secret room under the front steps of his house.

Rev. William King was born near Limavady in 1812, emigrated to America as a young man and eventually settled in Louisiana. Though he grew increasingly to abhor slavery, he himself owned a number of slaves and came into the possession of several more on the death of his father-in-law in 1846. In 1848 he took these slaves to Ohio and set them free. A year later he established the Elgin settlement in Canada for former slaves.

11. Business and Commerce

Many Ulster-Scots contributed the commercial development of America. A largely forgotten figure is Oliver Pollock (1737–1823), who was born in the Bready area of County Tyrone and emigrated to America in 1760. He became involved in business which eventually took him to New Orleans where he became of one of the most prosperous merchants in America.

Pollock used his wealth to finance the activities of the American Revolutionaries in the Mississippi Valley, an important but little-known campaign. It is reckoned that he spent the modern equivalent of $1 billion of his own money on the war effort. Perhaps even more remarkably, Pollock is credited with inventing the dollar sign ($), one of the most recognisable symbols in the world.

Alexander Brown (1764–1834) was born in Ballymena and emigrated to Baltimore in 1800, founding the Irish Linen Warehouse. His business interests expanded and in his lifetime his company became the second largest foreign exchange dealer in America – behind the Second Bank of the United States.

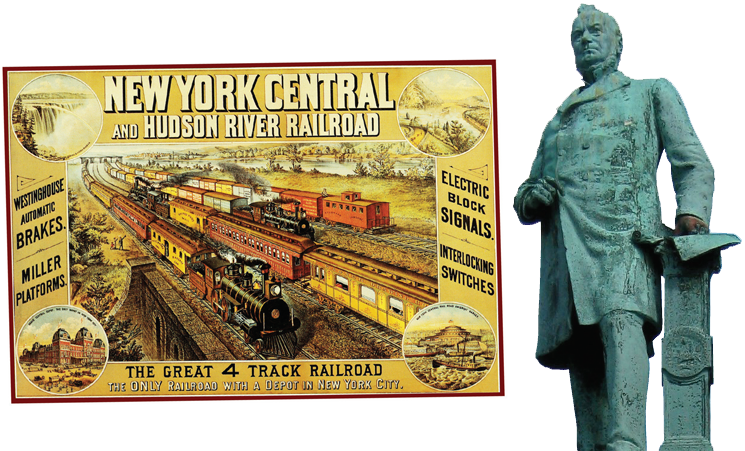

Alexander Turney Stewart (1803–76) from Lissue, near Lisburn, emigrated to America in his youth and went into business in New York, opening what is considered to be the first department store in the world – the ‘Great Iron Store’. He was also responsible for the development of Garden City on Long Island. Another Lisburn man who made a significant contribution to business in America was the railroad magnate Samuel (Sam) Sloan (1817– 1907), described as ‘one of the monarchs of the land … the actual rulers of the United States’. Sloan was also a founder of what is now Citibank.

In 1818 Andrew and Rebecca Mellon left Castletown, near Omagh (now the location of the Ulster American Folk Park), with their 5-year-old son Thomas to join the Mellons already settled in Pennsylvania. Thomas Mellon (1813–85) went on to have a successful career in banking and the family became one of the wealthiest in America. His son Andrew William was Secretary to the Treasury from 1921 to 1932 and founded the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC.

12. Manufacturers and Industrialists

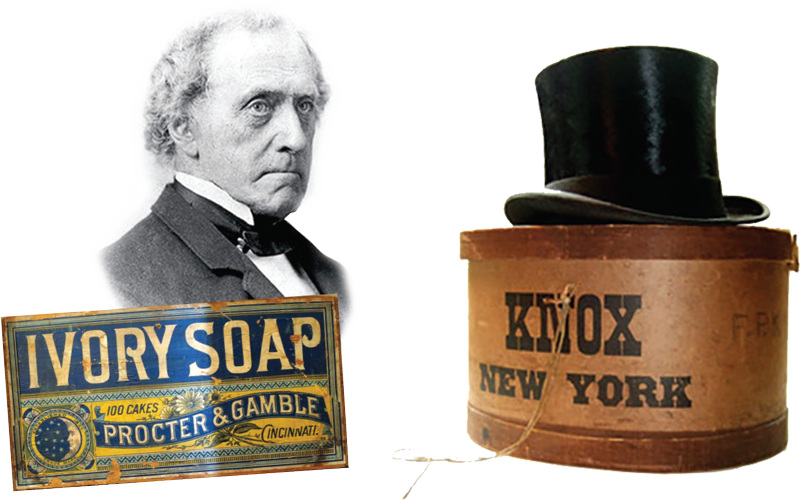

In manufacturing we find that Ulster-Scots made their mark, and in ways that can still be seen today. Born near Enniskillen, James Gamble (1803–91) emigrated with his family to America in 1819, settling in Cincinnati. Apprenticed to a soap-maker, he subsequently established his own business.

In 1837 Gamble formed a partnership with his brother-in-law, William Procter, a candle-maker. (It is said that their father-in-law encouraged the two men to consider working together.) The company, Procter & Gamble, has gone on to become one of the most successful firms of its kind in world history.

The opening up of the American Midwest provided many opportunities for manufacturers, especially those in the meat-processing business. Samuel Kingan (1824–1911), who was from near Ballynahinch, County Down, founded Kingan & Co. in 1852 and had factories in Brooklyn and Cincinnati. After both of these burned down, a plant was opened in Indianapolis in 1862. This facility adopted the most advanced manufacturing techniques and pioneered the use of refrigeration. In the 1860s members of the Sinclair family of Belfast expanding their pork processing business to America, initially to New York and later to Cedar Rapids, Iowa, where one of the world’s largest meat-packing plants was established. In 1875 the Kingan and Sinclair businesses merged.

A native of Ramelton, Charles Knox (1817–95) founded in New York City what became the largest hat manufacturing company in the world. Among the many customers of the Knox Hat Company were more than 20 US Presidents. Abraham Lincoln’s well-known ‘stovepipe’ hat was made by the firm.

Francis Torrance (1816–86), born near Letterkenny, County Donegal, into a family that traced its ancestry to Kirkintilloch, Scotland, established the Standard Manufacturing Co. in Pittsburgh in 1875, which pioneered the development and manufacture of plumbing and sanitation goods. Under his son, also named Francis, the business, renamed the Standard Sanitary Manufacturing Co., became the world’s largest producer of sanitation products.

13. Novelists, Journalists and Historians

Some of America’s leading writers have been Ulster-Scots / Scotch-Irish. From Edgar Allan Poe and Mark Twain to John Steinbeck and Stephen King, their work has spanned multiple genres and has defined the story of America.

David Ramsay (1749–1815), the son of parents from Ulster, possibly County Donegal, has been called the ‘father of American historical writing’. Among his many works was History of the American Revolution (1789), in which he was able to draw on his own personal experience of the events about which he was writing, and History of the United States (1816–17).

One of the most successful novelists of his day was Thomas Mayne Reid (1818–83). The son of the minister of Ballyroney Presbyterian Church, County Down, he emigrated to America and while in Philadelphia befriended Edgar Allan Poe, himself of Ulster ancestry. Reid was a prolific writer of adventure novels. Donegal-born John Wallace ‘Captain Jack’ Crawford became an adventurer, famous performer, poet and master storyteller. These romantic depictions of life on the range kindled America’s love affair with the Wild West.

A largely forgotten literary figure is James McHenry (1785–1845), a native of Larne, who is considered the first Irish American novelist. In 1817 he emigrated to America, eventually settling in Philadelphia where he was the founding editor of the American Monthly Magazine. In 1842 McHenry was appointed US Consul in Londonderry, bringing him back to Ireland, and he died in his hometown of Larne.

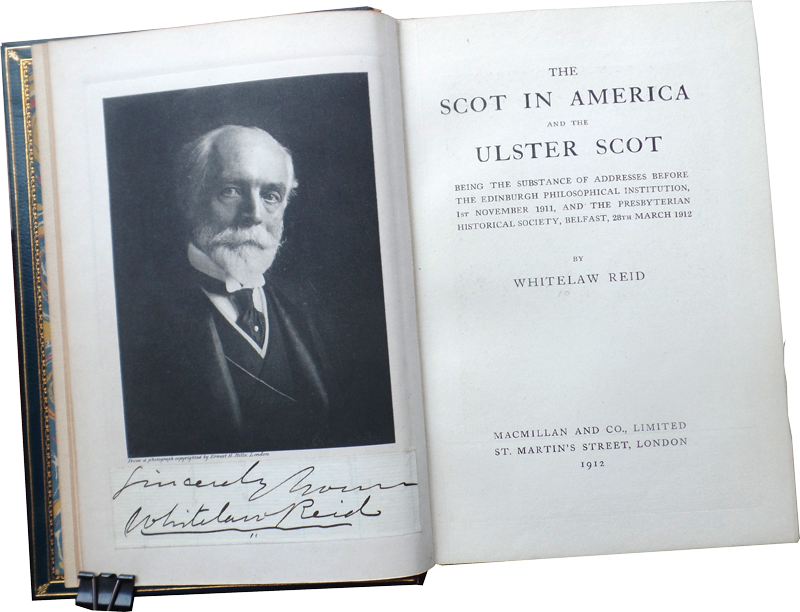

The New York Tribune was founded by ‘the conscience of America’, Horace Greeley, whose ancestors, the Woodburns, moved from Ulster to New England in the early 18th century. Of them, he wrote: ‘whose store of Scottish and Scotch-Irish traditions, songs, anecdotes, shreds of history &c, can have rarely been equalled.’ After Greeley’s death the newspaper was purchased by Whitelaw Reid, the descendant of immigrants from Tyrone, who was US Ambassador to France (1889–92) and the United Kingdom (1905–12). In April 1912 he visited Belfast to give a lecture on ‘The Scot in America and the Ulster Scot’.

14. Ulster Place-Names

Settlers from Ulster frequently named their new homes after the places they had left behind. Since 1718 Ulster placenames have been applied to farms, townships, villages, counties, towns and cities all over America.

For example, when the McFaddens arrived in Maine in 1718 they called their new home Somerset as it reminded them of Somerset on the River Bann in Ulster. Alexander Porter (d. 1833), who is credited with having helped to build much of downtown Nashville, named his house there ‘Tammany Woods’. Porter was a native of County Donegal, growing up on the family farm at Tamnawood, near Ballindrait.

Londonderry and Derry appear with regularity in those areas where Ulster-Scots settled in some numbers. This was a reflection not only of the city as a place of origin of many emigrants and as an important port of departure, but also of the symbolic value of Londonderry as the city that had withstood the siege of 1689. Arguably the best-known Londonderry in America is the settlement established in New Hampshire by migrants from the Bann Valley. Originally known as Nutfield, the name of this settlement was changed to Londonderry in 1722. Many of the early families in this Londonderry had been involved in one way or another in the siege, including their minister, Rev. James McGregor.