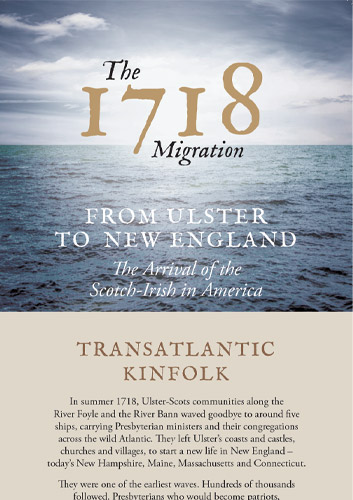

1718 Migration from Ulster to New England

The Arrival of the Scotch-Irish in America

Transatlantic Kinfolk

In summer 1718, Ulster-Scots communities along the River Foyle and the River Bann waved goodbye to around five ships, carrying Presbyterian ministers and their congregations across the wild Atlantic. They left Ulster’s coasts and castles, churches and villages, to start a new life in New England – today’s New Hampshire, Maine, Massachusetts and Connecticut.

They were one of the earliest waves. Hundreds of thousands followed. Presbyterians who would become patriots, pioneers and Presidents.

Today, over 20 million Americans have Scotch-Irish ancestry. This is our shared story.

Related Documents

The 1718 Migration

From Ulster to New England - The Arrival of the Scotch-Irish in America.

7.11 MB

Reflections on 300 years of the Scots Irish in Maine

1718-2018

8.29 MB

Related Videos

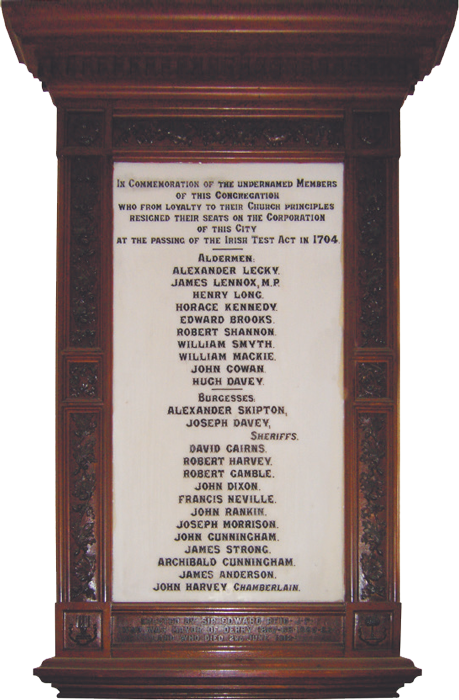

‘Test Act’ Laws and Discrimination

Presbyterians were particularly aggrieved when a law known as the ‘Test Act’ was introduced to Ireland in 1704. Those wishing to hold public office would have to produce evidence that they had taken communion in the Church of Ireland – this effectively barred Presbyterians. Marriages conducted by Presbyterian ministers were not recognised, and children born of such marriages were considered illegitimate. The writer Jonathan Swift, an Anglican cleric, is believed to have been the author of a pamphlet which described Ulster Presbyterians as a ‘knavish, wicked, thievish race’.

Presbyterians were particularly aggrieved when a law known as the ‘Test Act’ was introduced to Ireland in 1704. Those wishing to hold public office would have to produce evidence that they had taken communion in the Church of Ireland – this effectively barred Presbyterians. Marriages conducted by Presbyterian ministers were not recognised, and children born of such marriages were considered illegitimate. The writer Jonathan Swift, an Anglican cleric, is believed to have been the author of a pamphlet which described Ulster Presbyterians as a ‘knavish, wicked, thievish race’.

Situation For Presbyterians

Life in Ulster for Presbyterians in the 1600s had not been easy. The 105-day long Siege of Derry in 1689 – the longest in British and Irish history – pitted the forces of King James II against the people. An estimated 15,000 people died of fever, starvation or were killed. The end of the Siege was reportedly heralded by a boy named James McGregor who climbed to the top of the city Cathedral to fire a cannon. Ulster’s Presbyterians enjoyed a brief era of liberty under the new King William III, but when William died in 1702, anti-Presbyterian persecution returned.

Life in Ulster for Presbyterians in the 1600s had not been easy. The 105-day long Siege of Derry in 1689 – the longest in British and Irish history – pitted the forces of King James II against the people. An estimated 15,000 people died of fever, starvation or were killed. The end of the Siege was reportedly heralded by a boy named James McGregor who climbed to the top of the city Cathedral to fire a cannon. Ulster’s Presbyterians enjoyed a brief era of liberty under the new King William III, but when William died in 1702, anti-Presbyterian persecution returned.

Marble plaque, First Derry Presbyterian Church, Londonderry, Northern Ireland. After the Siege of Derry, a Presbyterian meeting house was built within the city’s famous walls with a large donation provided by Queen Mary II, who was both the wife of the new King and daughter of the old one. However by 1702, William and Mary were dead and their successor, Queen Anne, introduced the ‘Test Act’ laws. In 1704, 24 members of the congregation resigned from the Londonderry Corporation as a result of the Test Act –

1630s: Voyage of Eagle Wing

In the 1630s communications took place between leading figures from the Massachussetts Bay colony and Ulster Presbyterian ministers. An agent made an exploratory visit to New England, and John Winthrop (the younger) visited Ulster on at least two occasions. The General Court of Massachussetts approved a tract of land on the south banks of the Merrimack River for these Ulster emigrants to settle. Their ship – Eagle Wing – set sail in September 1636 with 140 passengers, but due to severe storms had to turn back. Cotton Mather referred to this attempted migration in his Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) and in a letter to Rev John Woodside in February 1718.

In the 1630s communications took place between leading figures from the Massachussetts Bay colony and Ulster Presbyterian ministers. An agent made an exploratory visit to New England, and John Winthrop (the younger) visited Ulster on at least two occasions. The General Court of Massachussetts approved a tract of land on the south banks of the Merrimack River for these Ulster emigrants to settle. Their ship – Eagle Wing – set sail in September 1636 with 140 passengers, but due to severe storms had to turn back. Cotton Mather referred to this attempted migration in his Magnalia Christi Americana (1702) and in a letter to Rev John Woodside in February 1718.

1680s: Rev Francis Makemie

In the late 1600s a sizeable Ulster-Scots community developed in Somerset County, on the eastern shore of Maryland. In 1680, Englishman Colonel William Stevens, who owned land at Rehobeth, Maryland, wrote directly to the ‘Presbytery of the Laggan’ in Donegal requesting that a minister be sent for these people. In 1683 the young Rev Francis Makemie – ‘The Father of American Presbyterianism’ – arrived and began a pioneering ministry that lasted for 25 years. Other Ulster ministers such as Rev William Traill and Rev William Holmes went too.

In the late 1600s a sizeable Ulster-Scots community developed in Somerset County, on the eastern shore of Maryland. In 1680, Englishman Colonel William Stevens, who owned land at Rehobeth, Maryland, wrote directly to the ‘Presbytery of the Laggan’ in Donegal requesting that a minister be sent for these people. In 1683 the young Rev Francis Makemie – ‘The Father of American Presbyterianism’ – arrived and began a pioneering ministry that lasted for 25 years. Other Ulster ministers such as Rev William Traill and Rev William Holmes went too.

Warner House, Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Archibald MacPheadris actively sought out families from Ulster to emigrate to New England. Probably from Ballymoney, MacPheadris established a successful business in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, where his home – now called the Warner House – still stands.

Makemie statue, Philadelphia

Rev William Boyd

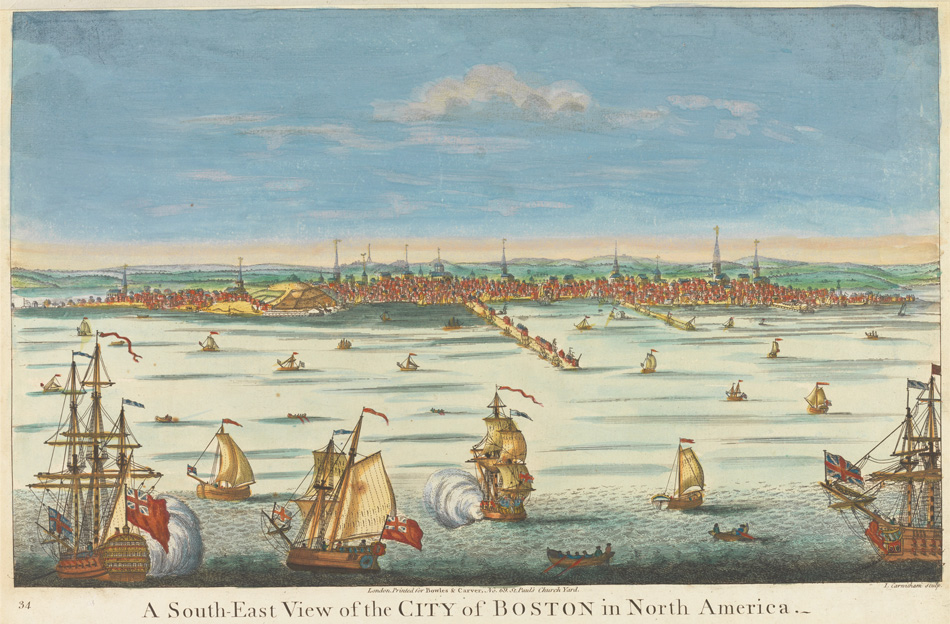

The petition was carried to New England by Rev William Boyd, the minister of Macosquin Presbyterian Church near Coleraine. It is thought that his father was Rev. Thomas Boyd who had been in Londonderry during the siege of 1689. On his arrival in Boston in July 1718 Boyd met with the local authorities. They were keen to have new settlers, especially people used to farming and frontier life; the colonial government thought that Ulster settlers could be placed on the outer reaches of their colony. Rev Increase Mather wrote that Boyd was a man distinguished ‘by the Exemplary holiness of his Conversation, and the Eminency of his Ministerial Gifts’.

The petition was carried to New England by Rev William Boyd, the minister of Macosquin Presbyterian Church near Coleraine. It is thought that his father was Rev. Thomas Boyd who had been in Londonderry during the siege of 1689. On his arrival in Boston in July 1718 Boyd met with the local authorities. They were keen to have new settlers, especially people used to farming and frontier life; the colonial government thought that Ulster settlers could be placed on the outer reaches of their colony. Rev Increase Mather wrote that Boyd was a man distinguished ‘by the Exemplary holiness of his Conversation, and the Eminency of his Ministerial Gifts’.

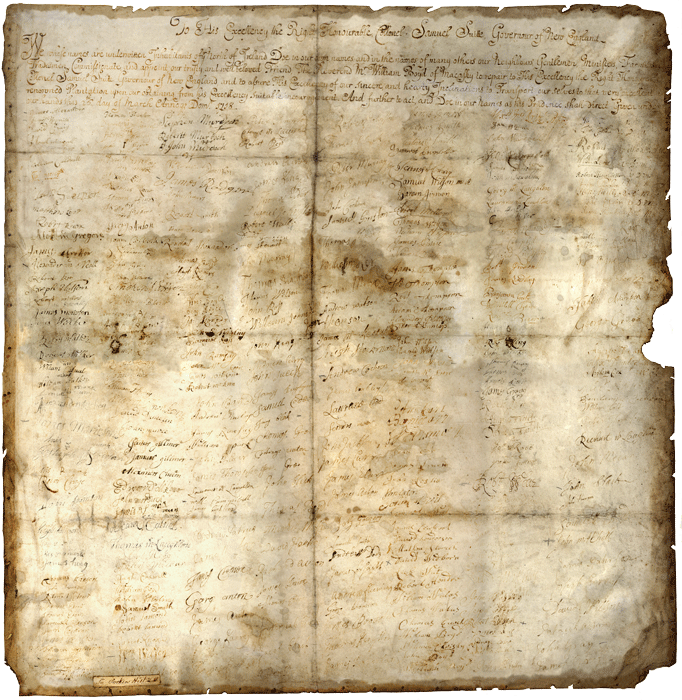

‘Precious in The Eyes of New England’

The Shute Petition has been a treasured artefact for the past three centuries. In May 1890, it was displayed at the Scotch-Irish Society of the United States annual congress at the Machinery Hall in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was read aloud by Arthur L. Perry, Professor of Political Economy and History at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, who said:

‘... when I looked upon this tattered and worn piece of parchment, it inspired in me feelings of increased reverence for our noble ancestors … the eagerness of our forefathers to leave the land of oppression for the shores of the free ... precious in the eyes of New England, nay precious in the eyes of Scotch-Irishmen everywhere, is this venerable muniment of intelligence and courageous purpose.’

The Shute Petition has been a treasured artefact for the past three centuries. In May 1890, it was displayed at the Scotch-Irish Society of the United States annual congress at the Machinery Hall in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. It was read aloud by Arthur L. Perry, Professor of Political Economy and History at Williams College, Williamstown, Massachusetts, who said:

‘... when I looked upon this tattered and worn piece of parchment, it inspired in me feelings of increased reverence for our noble ancestors … the eagerness of our forefathers to leave the land of oppression for the shores of the free ... precious in the eyes of New England, nay precious in the eyes of Scotch-Irishmen everywhere, is this venerable muniment of intelligence and courageous purpose.’

Petition to Governor Samuel Shute from the ‘Inhabitants of the North of Ireland’ (26 March 1718). Courtesy of the New Hampshire Historical Society.

Rev James McGregor

James McGregor, the boy who had experienced the Siege of Derry in 1689, was to become a ‘Moses-like’ figure in this great exodus story. He was now minister of Aghadowey Presbyterian Church, but the financial hardship of Ulster caused him to take his own family and many others from the congregation to America. In his farewell sermon he said they were leaving ‘to avoid oppression and cruel bondage, to shun persecution and designed ruin, to withdraw from the communion of idolators and to have an opportunity of worshipping God according to the dictates of conscience and the rules of His inspired Word.’

James McGregor, the boy who had experienced the Siege of Derry in 1689, was to become a ‘Moses-like’ figure in this great exodus story. He was now minister of Aghadowey Presbyterian Church, but the financial hardship of Ulster caused him to take his own family and many others from the congregation to America. In his farewell sermon he said they were leaving ‘to avoid oppression and cruel bondage, to shun persecution and designed ruin, to withdraw from the communion of idolators and to have an opportunity of worshipping God according to the dictates of conscience and the rules of His inspired Word.’

Ships, Ports and Place-Names

A number of ships (such as the William and Mary, Maccallum, William and Elizabeth, Mary and Elizabeth, Robert and William) set sail from the ports of Coleraine and Londonderry in Ulster, carrying up to 1000 people. They arrived in Boston during late summer and early autumn, but were not enthusiastically welcomed by the Massachusetts Puritans. The migrants had to split up – one group headed north to Casco Bay, Maine where they endured a freezing winter. The following spring they sailed to the mouth of the Merrimack River and then travelled inland to an area called Nutfield; McGregor had been in Dracut, but he joined them at Nutfield in April 1719.

Like many familiar Ulster places, these two emigration ports were brought by the emigrants to New England. In 1722 Nutfield was renamed Londonderry; and in 1743, ‘Boston Township No 2’ in Massachusetts was renamed Colrain.

A number of ships (such as the William and Mary, Maccallum, William and Elizabeth, Mary and Elizabeth, Robert and William) set sail from the ports of Coleraine and Londonderry in Ulster, carrying up to 1000 people. They arrived in Boston during late summer and early autumn, but were not enthusiastically welcomed by the Massachusetts Puritans. The migrants had to split up – one group headed north to Casco Bay, Maine where they endured a freezing winter. The following spring they sailed to the mouth of the Merrimack River and then travelled inland to an area called Nutfield; McGregor had been in Dracut, but he joined them at Nutfield in April 1719.

Like many familiar Ulster places, these two emigration ports were brought by the emigrants to New England. In 1722 Nutfield was renamed Londonderry; and in 1743, ‘Boston Township No 2’ in Massachusetts was renamed Colrain.

Detail from the headstone of Rev. James McGregor in Forest Hill Cemetery. Courtesy Heather Wilkinson Rojo.

A view of Boston, 1720

The McKeen Family

These brothers were well-to-do merchants in Ballymoney, County Antrim. They apparently sought refuge in Londonderry during the Williamite War. John died shortly before the planned departure in 1718, but his widow, three sons and daughter Janet travelled with James and other family members and neighbours to New England. Janet’s memories of arriving in America were recorded around 1785 by her granddaughter - she remembered 16 people without enough money to emigrate who had indentured themselves to her father, and she recalled that the travellers sang Psalms when they arrived in Boston on the Sabbath.

These brothers were well-to-do merchants in Ballymoney, County Antrim. They apparently sought refuge in Londonderry during the Williamite War. John died shortly before the planned departure in 1718, but his widow, three sons and daughter Janet travelled with James and other family members and neighbours to New England. Janet’s memories of arriving in America were recorded around 1785 by her granddaughter - she remembered 16 people without enough money to emigrate who had indentured themselves to her father, and she recalled that the travellers sang Psalms when they arrived in Boston on the Sabbath.

James and Janet Gregg

James was born in Scotland c. 1670, and moved with his parents to Macosquin, County Londonderry, c. 1690. He was a linen draper and tailor, and it is said that he met Janet – the sister-in-law of Rev James McGregor – when she came into his shop to be measured for wedding clothes. She was unwillingly being married to an older man called Lindsay, to whom her parents owed money. She and James eloped that evening and were married by the curate of a neighbouring parish. Their son William Gregg, born in Ireland c. 1695, became the principal surveyor who laid out property lots in the new settlement of Londonderry.

James was born in Scotland c. 1670, and moved with his parents to Macosquin, County Londonderry, c. 1690. He was a linen draper and tailor, and it is said that he met Janet – the sister-in-law of Rev James McGregor – when she came into his shop to be measured for wedding clothes. She was unwillingly being married to an older man called Lindsay, to whom her parents owed money. She and James eloped that evening and were married by the curate of a neighbouring parish. Their son William Gregg, born in Ireland c. 1695, became the principal surveyor who laid out property lots in the new settlement of Londonderry.

Ocean-Born Mary

Mary Wilson was born in 1720 on board the ship on which her parents, James and Elizabeth Wilson, were travelling to America. The story goes that a pirate attacked their vessel, and threatened all on board with death, but on hearing the baby’s cries he said if they named the child Mary, after his mother, he would spare the whole ship. He gave the child a bolt of green brocade material for her future wedding dress. Mary Wilson spent the rest of her life in Londonderry, New Hampshire.

Mary Wilson was born in 1720 on board the ship on which her parents, James and Elizabeth Wilson, were travelling to America. The story goes that a pirate attacked their vessel, and threatened all on board with death, but on hearing the baby’s cries he said if they named the child Mary, after his mother, he would spare the whole ship. He gave the child a bolt of green brocade material for her future wedding dress. Mary Wilson spent the rest of her life in Londonderry, New Hampshire.

The Boston Common flax spinning demonstration and Mary Miller. The newly-arrived Ulster-Scots women were expert flax spinners and linen weavers. In summer 1719 some of them gave a public demonstration of flax spinning on Boston Common. Mary Miller emigrated from Londonderry, Ulster, with her husband Samuel around 1720. They settled at Londonderry, New Hampshire, where it is said she ‘paid for 400 acres of land in fine linen, made entirely by her own hands’. Their grandson James Miller was born in Peterborough, New Hampshire, in 1776 and became Governor of Arkansas.

Maine

Families leaving Ulster in 1718 also settled in areas of coastal Maine. The Maccallum sailed from Londonderry, captained by James Law. It arrived at Boston in early September and then sailed on to Merrymeeting Bay. On board were around 20 families with Rev James Woodside, the Presbyterian minister of Dunboe near Coleraine.

Rev James Woodside

In November 1718 the people of Brunswick called Woodside to be their minister. Here he built a ‘garrison house, fortify’d with palisadoes & two large bastions’, which proved a vital place of refuge during an attack by American Indians in 1722. Woodside’s time in Maine was unhappy, however, and ‘after many and grievous calamities’ he set sail from Boston for London in 1720. In a petition to the King in 1723 he claimed to have brought over to New England some 40 families which together comprised over 160 people.

In November 1718 the people of Brunswick called Woodside to be their minister. Here he built a ‘garrison house, fortify’d with palisadoes & two large bastions’, which proved a vital place of refuge during an attack by American Indians in 1722. Woodside’s time in Maine was unhappy, however, and ‘after many and grievous calamities’ he set sail from Boston for London in 1720. In a petition to the King in 1723 he claimed to have brought over to New England some 40 families which together comprised over 160 people.

The McFadden Family

Andrew and Jane McFadden were among the earliest Ulster settlers in Maine, and had probably emigrated on the Maccallum. They named a daughter, as well as their new home on Merrymeeting Bay, after Somerset on the banks of the River Bann. In 1766 Jane’s story was written down:

‘… Jane Macfadden of Georgetown about 82 Years of Age testifyeth and Saith that She with her late husband Andrew Macfadden lived in the Town of Garvo in the County of Derry on the ban Water in Ireland … about Forty Six Years ago my Husband and I removed from Ireland to Boston and from Boston we moved down to Kennebeck-River and up the River to Merry Meeting Bay … As my husband was aclearing away the Trees to Merry-Meeting Bay he Said it was a very pleasant place and he thought it was like a place call’d Summersett on the ban Water in Ireland…’

Andrew and Jane McFadden were among the earliest Ulster settlers in Maine, and had probably emigrated on the Maccallum. They named a daughter, as well as their new home on Merrymeeting Bay, after Somerset on the banks of the River Bann. In 1766 Jane’s story was written down:

‘… Jane Macfadden of Georgetown about 82 Years of Age testifyeth and Saith that She with her late husband Andrew Macfadden lived in the Town of Garvo in the County of Derry on the ban Water in Ireland … about Forty Six Years ago my Husband and I removed from Ireland to Boston and from Boston we moved down to Kennebeck-River and up the River to Merry Meeting Bay … As my husband was aclearing away the Trees to Merry-Meeting Bay he Said it was a very pleasant place and he thought it was like a place call’d Summersett on the ban Water in Ireland…’

Archaeological excavations at the McFadden homestead

The Dinsmoors

The Dinsmoor family emigrated from Ulster to America in the 1720s. John Dinsmoor first settled at Fort George, Maine, where he initially enjoyed a positive relationship with the Penobscot Indians – ‘calling him and themselves all one brother’ – but was later taken captive. On his release he went to Londonderry, New Hampshire where he renewed old Ulster acquaintances and was granted 100 acres of land.

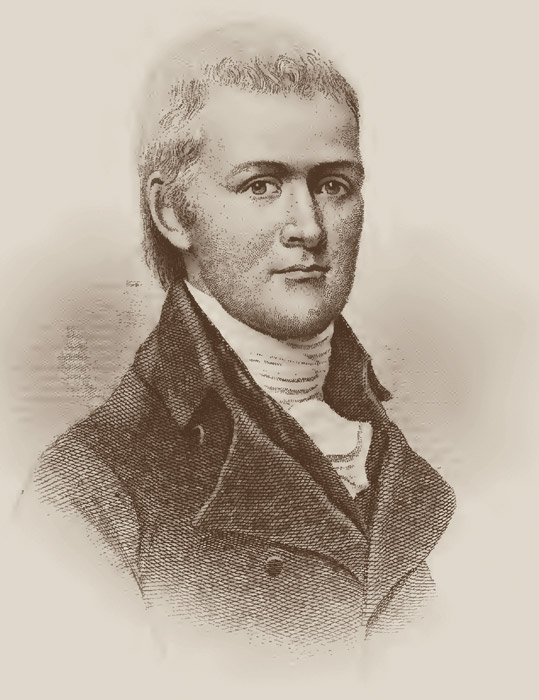

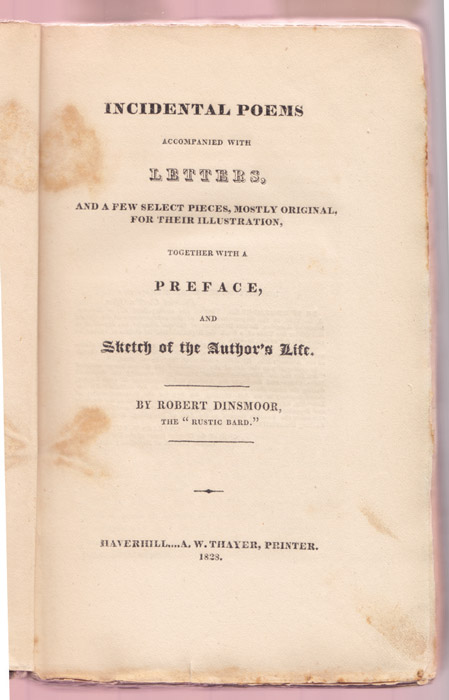

Robert Dinsmoor, The ‘Rustic Bard’

Robert Dinsmoor was John’s great grandson, and was born in Windham, New Hampshire in 1757. He was a renowned local poet and in 1828 a collection of his Incidental Poems were published in Haverhill, which included a family biography. Some were written to be sung to traditional Scottish and Ulster tunes such as Scots Wha Hae and Boyne Water. Many of the poems use Scots language words and expressions, best known around the world through the poems of Robert Dinsmoor’s contemporary, Robert Burns, Scotland’s National Bard.

Robert Dinsmoor was John’s great grandson, and was born in Windham, New Hampshire in 1757. He was a renowned local poet and in 1828 a collection of his Incidental Poems were published in Haverhill, which included a family biography. Some were written to be sung to traditional Scottish and Ulster tunes such as Scots Wha Hae and Boyne Water. Many of the poems use Scots language words and expressions, best known around the world through the poems of Robert Dinsmoor’s contemporary, Robert Burns, Scotland’s National Bard.

Jamie Cochran

The 1718 migration story was told in Dinsmoor’s poem Jamie Cochran:

In Ulster Province, Erin’s northern strand

Five shiploads joined to leave that far off land.

They had their ministers to pray and preach

These twenty families embarked in each.

Here I would note and have it understood,

Those emigrants were not Hibernian blood,

But sturdy Scotsmen true, whose fathers fled

From Argyllshire, where protestants had bled

In days of Stuart Charles and James second

Where persecution was a virtue reckoned,

They found shelter on the Irish shore

In Ulster, not a century before

Four of these ships at Boston harbor landed;

The fifth, by chance at Casco Bay was stranded…

The 1718 migration story was told in Dinsmoor’s poem Jamie Cochran:

In Ulster Province, Erin’s northern strand

Five shiploads joined to leave that far off land.

They had their ministers to pray and preach

These twenty families embarked in each.

Here I would note and have it understood,

Those emigrants were not Hibernian blood,

But sturdy Scotsmen true, whose fathers fled

From Argyllshire, where protestants had bled

In days of Stuart Charles and James second

Where persecution was a virtue reckoned,

They found shelter on the Irish shore

In Ulster, not a century before

Four of these ships at Boston harbor landed;

The fifth, by chance at Casco Bay was stranded…

One of the poems was written to Silas Dinsmoor (1766–1847) subtitled ‘in Scotch, the dialect of their ancestors.’ Silas was born at Windham but later moved to Alabama and then Kentucky. His mother was a McKeen, making him a first cousin to Thomas McKean, who signed the Declaration of Independence, and Joseph McKeen, the first president of Bowdoin College. Thomas Jefferson appointed Silas Dinsmoor as Agent to the Choctaw.

Title page of Dinsmoor’s first edition, 1828. A second edition was published in 1898.

A Dinsmoor homestead in Windham, established 1736.

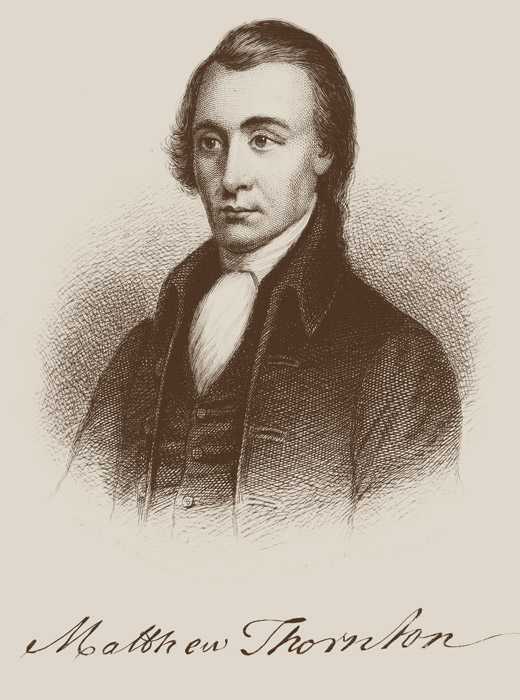

Matthew Thornton

The Ulster-Scots and Scotch-Irish were at the forefront of the American Revolution. Having endured and defied the persecutions of successive tyrant monarchs in the 1600s, they left for America with that lived experience in their memories. These stories were passed down through the generations, equipping their descendants to stand for liberty and independence.

‘Rigid Presbyterians Who Had Fled Scotland’

The Thorntons have been described as ‘rigid Presbyterians who had fled from Scotland to avoid the persecutions of Charles II. Many of these colonists and their descendants subsequently emigrated from Ireland to America where they became known as the Scotch-Irish’.

James and Elizabeth Thornton emigrated to Maine from Londonderry, Ulster, with their four-year-old son Matthew, around 1718. In 1738 James Thornton helped found a new town in Massachusetts, which was to be settled by ‘inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ireland or their descendants being Protestants … of the Presbyterian persuasion as used in the Church of Scotland’. The town was initially called Lisburn, named after the town in Ulster, but was later renamed Pelham.

The Thorntons have been described as ‘rigid Presbyterians who had fled from Scotland to avoid the persecutions of Charles II. Many of these colonists and their descendants subsequently emigrated from Ireland to America where they became known as the Scotch-Irish’.

James and Elizabeth Thornton emigrated to Maine from Londonderry, Ulster, with their four-year-old son Matthew, around 1718. In 1738 James Thornton helped found a new town in Massachusetts, which was to be settled by ‘inhabitants of the Kingdom of Ireland or their descendants being Protestants … of the Presbyterian persuasion as used in the Church of Scotland’. The town was initially called Lisburn, named after the town in Ulster, but was later renamed Pelham.

‘Unconstitutional and Tyrannical’

Matthew Thornton spent his early years in Maine and Massachussetts, before settling in Londonderry, New Hampshire in 1740. He was a physician and Colonel of the militia. He married Hannah Jack, also of Ulster-Scots parentage. In 1775 Thornton denounced the ‘unconstitutional and tyrannical Acts of the British Parliament’, helped to draft the first state constitution and was selected for the Continental Congress. He was one of the 56 who signed the Declaration of Independence, and one of three Ulster-born signatories.

He died in 1803, aged 89, in Newburyport while visiting his daughter Hannah McGaw. He was buried at Thornton’s Ferry, New Hampshire.

Matthew Thornton spent his early years in Maine and Massachussetts, before settling in Londonderry, New Hampshire in 1740. He was a physician and Colonel of the militia. He married Hannah Jack, also of Ulster-Scots parentage. In 1775 Thornton denounced the ‘unconstitutional and tyrannical Acts of the British Parliament’, helped to draft the first state constitution and was selected for the Continental Congress. He was one of the 56 who signed the Declaration of Independence, and one of three Ulster-born signatories.

He died in 1803, aged 89, in Newburyport while visiting his daughter Hannah McGaw. He was buried at Thornton’s Ferry, New Hampshire.

Matthew Thornton (1713-1803), an Ulster-born signer of the Declaration of Independence

Matthew Thornton stone on the 56 Signers Monument, National Mall, Washington DC.

Belfast, Maine

One of the 35 Scotch-Irish founders of Belfast was John Davidson, whose parents emigrated to America from Moneymore in County Londonderry around 1728, following the brutal robbery and murder of their own parents. In his 1832 Reminiscences, John Davidson said ‘my ancestors on both my father and mother’s side were both from Scotland; were by profession what was then Protestants, they embarked to the north of Ireland … from that they call us Scotch Irish, we are called so to this day’.

The Davidsons initially settled in Woburn, Massachusetts, then Tewkesbury and then Windham, where they were friends of the Dinsmoor family. John’s father bought him a plot of land at Belfast which today is Moose Point State Park. The town was incorporated in 1773.

One of the 35 Scotch-Irish founders of Belfast was John Davidson, whose parents emigrated to America from Moneymore in County Londonderry around 1728, following the brutal robbery and murder of their own parents. In his 1832 Reminiscences, John Davidson said ‘my ancestors on both my father and mother’s side were both from Scotland; were by profession what was then Protestants, they embarked to the north of Ireland … from that they call us Scotch Irish, we are called so to this day’.

The Davidsons initially settled in Woburn, Massachusetts, then Tewkesbury and then Windham, where they were friends of the Dinsmoor family. John’s father bought him a plot of land at Belfast which today is Moose Point State Park. The town was incorporated in 1773.

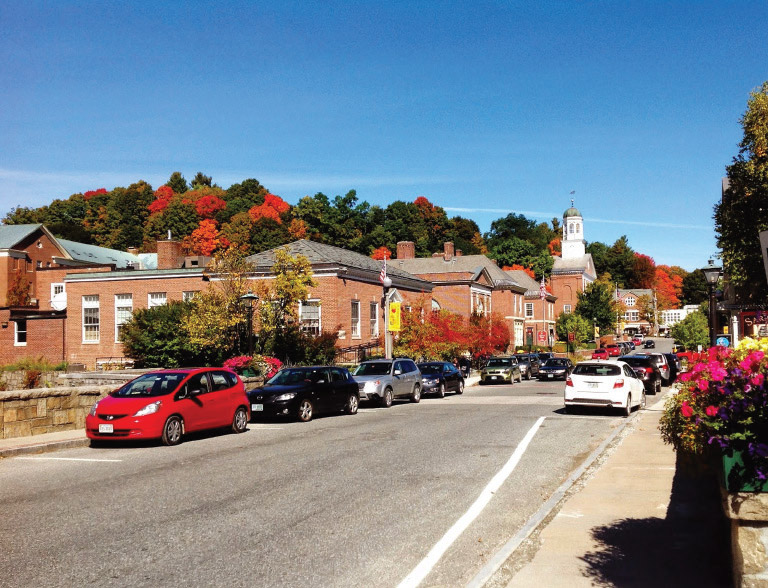

Peterborough, New Hampshire

Peterborough dates from 1739 but grew rapidly in 1759 with the arrival of ‘forty five or fifty families from Lunenburg, Londonderry, and some immediately from Ireland. They all, however belonged to the same stock. They came to this country from the north of Ireland, and were usually called Scotch-Irish’.

In 1839 a descendant of one of these pioneering families, John Hopkins Morison, published a wonderful centennial book charting the town’s history and retelling the traditions of the Siege of Derry. He interviewed the oldest residents such as Sarah M’Nee, then 97 years old, who had been born in Ulster. She remembered their arrival in Boston.

Morison described their homes – a dresser, fireplace, tales of olden days, ‘the preeminence of Ireland’, and a family Bible from which a chapter would be read and then prayers offered.

Peterborough dates from 1739 but grew rapidly in 1759 with the arrival of ‘forty five or fifty families from Lunenburg, Londonderry, and some immediately from Ireland. They all, however belonged to the same stock. They came to this country from the north of Ireland, and were usually called Scotch-Irish’.

In 1839 a descendant of one of these pioneering families, John Hopkins Morison, published a wonderful centennial book charting the town’s history and retelling the traditions of the Siege of Derry. He interviewed the oldest residents such as Sarah M’Nee, then 97 years old, who had been born in Ulster. She remembered their arrival in Boston.

Morison described their homes – a dresser, fireplace, tales of olden days, ‘the preeminence of Ireland’, and a family Bible from which a chapter would be read and then prayers offered.

Belfast, Maine

Peterborough, New Hampshire

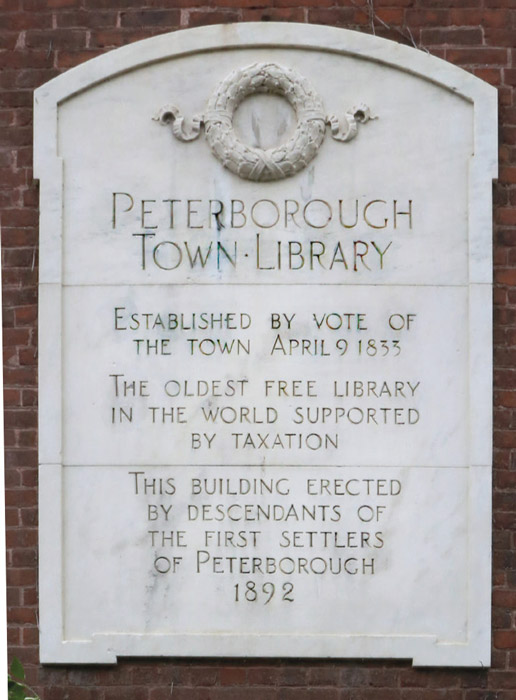

Morison was one of the founders of Peterborough Town Library in 1833 – the first in the world to be funded through taxation. Belfast, Maine Peterborough, New Hampshire IN