‘Sea of Blue’ Flax growing in the Laggan

In the course of the 1700s the province of Ulster became the most prosperous part of Ireland. The single most important reason for this was the rise of the linen industry.

Flax provided the basic ingredient of this industry and at one time Donegal was the leading flax-producing county in Ireland.

The flax harvest

The flax harvest was one of the high points of the summer. Flax – or lint as it was frequently called – was pulled, not cut, and this was laborious work. The pulled flax was tied up in sheaves and was then placed in a dam. This process was known as retting and the pungent smell that it generated was notorious. The flax remained in the dam for up to a fortnight and was then spread out to dry. Kilns were also used to dry flax and these were once a common feature of the Laggan countryside.

“ Everywhere the people were busily employed taking the flax out of steep, or spreading it on the ground. I suppose I need not tell the reader, that when he travels through a flax country at this season, he will do well to provide himself with a smelling-bottle. The smell of the spread-out flax is most unpleasant; but I could not learn that the odour is unwholesome.”

From a traveller through the Laggan in 1834

Flax mills

Once dried, the flax was taken to a flax (or scutch) mill where the fibre was separated from the woody stems. The typical Irish flax mill is believed to have been developed in Donegal in the mid 1700s. In 1760 it was said of Donegal, ‘There is a great number of flax mills in this county’. In the mid-nineteenth century the densest concentration of flax mills in Ireland was in the Laggan. Scutching was dangerous work and many injuries were sustained by those who worked in these mills.

Textile production

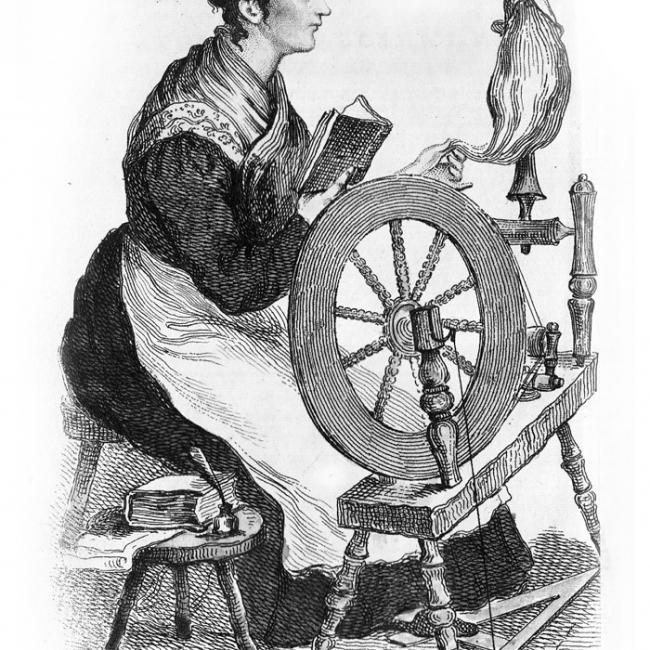

Spinning the flax into yarn was traditionally a role for women. Weaving was generally carried out by men and in the 1700s ‘Laggans’ was the name given to a locally made linen cloth. These activities provided an important supplement to the family’s income from farming. However, technological advances in textile production in the 1800s largely put an end to this domestic industry.

The end of an era

Flax production declined across Ulster in the early twentieth century. There was a brief revival during the Second World War and in 1940 the newly formed Donegal Flax Company built a modern scutch mill in Carrigans. However, this was not to last and by the 1950s flax production had all but disappeared from Donegal.

Toilers of the soil

The farming community

The farming community has been the backbone of the Laggan for centuries. Many of the farms in the Laggan have been in the same family for generations. Furthermore, a good number of the farming families can trace their origins back to the settlements of the seventeenth century.

Farming in the Laggan

Farming life in the Laggan has changed enormously over the centuries. The intensification of farming, particularly from the eighteenth century onwards, has had a huge impact on the countryside we see today. Reclamation and improvement schemes, such as those along the shores of Lough Swilly, have increased the amount of pasture and arable land. The main cereal crop was once oats, but this has now given way to barley, while flax cultivation has disappeared.

"Between Derry and Letterkenny the farms are tolerably large, the grass was apparently good, most of the ploughing excellent, and the yards furnished with regiments of the characteristic little Scotch cornstacks. There are hedges, too, and in some cases the land is tilled almost to the hilltops …”

The Manchester Guardian, 1897

Landlord and tenant

Until the late 1800s the farmers in the Laggan did not own their farms outright, but were tenants paying rent to a landlord. The largest landed estates in the Laggan were those owned by the Hamiltons, Dukes of Abercorn (c. 16,000 acres), and the Forwards, Earls of Wicklow (c. 6,400 acres). Both families lived elsewhere and relied on agents to manage their Donegal properties.

From the middle of the 1800s the Tenant Right movement became increasingly strong in Donegal. Local Presbyterians, including members of the clergy, were heavily involved in setting up associations that demanded greater protections for the rights of tenant farmers.

Tenant right became a powerful electoral issue. In the 1880 general election in Donegal Rev. John Kinnear, a Presbyterian minister in Letterkenny and a prominent campaigner for Tenant Right, defeated the Marquess of Hamilton, son of the Duke of Abercorn.

Eventually, as a result of legislation passed in Parliament in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the landed estate system was broken up. Farmers now became the proprietors of the land they worked.