The Bruces and Ireland

After Bannockburn – Operation: Ireland (1315–1318)

Their ancestors had lands in Ulster. Their grandfather had signed an alliance with Ulster Lords. The older brother’s wife was from Ulster. The younger brother spent his youth in Ulster. The older brother became King of Scotland. The younger brother became King of Ireland. This is the story of The Bruces and Ireland.

The Bruce Campaign in Ireland

On 23/24 June 1314 the forces of Robert Bruce won a stunning victory at Bannockburn over a much larger English army. It was the culmination of a campaign that began in 1307, shortly after Bruce returned from Rathlin Island, off the north coast of County Antrim, where he had sought refuge for a number of months. Despite the crushing Scots victory at Bannockburn, Robert Bruce’s claim to the title King of Scotland was not recognised by Edward II of England, without which there could be no lasting peace.

Around the same time, the leading Gaelic Irish figure in Ulster, Domhnall Ó Neill, king of Tyrone, a distant cousin of the Bruces, was finding himself threatened by Richard de Burgh, the Earl of Ulster – Robert Bruce’s father-in-law. Ó Neill looked to Scotland and to Robert Bruce for assistance, encouraging the victor at Bannockburn to send a Scots army to Ireland to fight the Anglo-Normans.

Sending an army to Ireland suited Robert Bruce’s strategic political and military aims for it allowed him to open a second front by instigating his pan-Gael scheme of surrounding Edward II with rebellious subjects in his western dominions.

Sending an army to Ireland suited Robert Bruce’s strategic political and military aims for it allowed him to open a second front by instigating his pan-Gael scheme of surrounding Edward II with rebellious subjects in his western dominions.

His young brother Edward seems to have needed little encouragement to lead the campaign in Ireland. Indeed, many see him as being the prime instigator of it and that he was motivated by dynastic ambitions of his own. As John Barbour, author of The Brus (1375) states, Edward, ‘with great joy in his heart, and with the consent of the king, gathered to him men of great valour.’

St John’s Tower, Bruce Crescent, Ayr. A black marble plaque within the park reads ‘To commemorate the Parliament of King Robert the Bruce at this Church of St John the Baptist on 26th April 1315’.

It was this Parliament which approved Edward Bruce’s mission to Ireland. He set sail from Ayr to Antrim one month later.

25th May 1315 - The Landing at Larne Lough

The army assembled for the invasion of Ireland in May 1315 was probably not much smaller than the Scottish army at Bannockburn and no doubt included many of the veterans of that battle. Barbour states that ‘It was a great enterprise they undertook when, as few as they were, being no more 6,000 men, they set out to attack all Ireland’.

The place of departure was Ayr, then the most strategically important port on the south-west coast of Scotland, and the location of Robert Bruce’s recent assembly that endorsed the campaign. It can be safely assumed that the core of the fleet was the West Highland galleys and birlinns supplied by two key allies of the Bruce’s – Ailean Macruari, ‘King of the Isles’, and Alexander Macdonald, ‘King of Argyll’.

According to Barbour’s account, the Scottish fleet ‘arrived safely … without skirmish or attack and sent their ships everyone home.’ Barbour specifies the location for the landing as ‘Wolringis Fyrth’, i.e., Viking’s Forth, which has traditionally been understood as being Larne Lough. Another source refers to ‘Clandonne’ which has been interpreted as either Clondunmales (now Drumalis, Larne) or possibly Glendun further up the coast. It is likely that a large fleet would have needed multiple landing locations.

The story of the arrival of the Scottish army in the Larne area was passed down through the generations and was well known in the nineteenth century. In 1899, the brochure produced for the Larne Grand Fete featured on its front cover an illustration recreating the arrival of Bruce and his fleet. In 1976, a re-enactment event was held in Larne entitled ‘The Bruce Cavalcade’ when hundreds of people lined the streets.

Larne Lough. Bruce’s fleet is likely to have landed at multiple locations along the east Antrim coastline - a stretch of land which had been granted to his ancestors by King John in the early 1200s. An artists impression of the landing featured on the programme for Larne Grand Fete in 1899. An estimated 2 million people every year sail by ferry between Scotland and Northern Ireland.

June 1315 - The ‘Coronation’ of Edward at Carrickfergus

Having landed on the east coast of County Antrim, the Scottish forces regrouped and prepared for their onward journey. They were immediately confronted by an Anglo-Norman force of 20,000 led by the Mandevilles, Bissets, Logans and Savages, who Barbour describes as ‘the flower of Ulster’. This battle took place in the vicinity of Mounthill where a cairn once marked the battlefield.

Afterwards the Scots moved on to Carrickfergus, the most important Anglo-Norman stronghold in Ulster with its imposing castle standing sentinel over Belfast Lough. Alongside the castle a town had developed which was a centre of trade and commerce. The Bruce forces seized the town of Carrickfergus – but not the castle which held out for over a year longer – and established what would effectively be their base camp for the duration of the campaign.

According to Barbour, shortly after taking Carrickfergus ‘... the folk of Ulster had come entirely to his (Edward Bruce’s) peace … there came to him and made fealty some of the kings of that country, a good ten or twelve ...’. Historians have interpreted this moment as what could be described as Edward Bruce’s ‘coronation’ as King of Ireland. In the Irish annals for 1315, it is recorded that ‘the Ulstermen consented to his being proclaimed King of Ireland and all the Gaels of Ireland agreed to grant him lordship and they called him King of Ireland.’

Two years later, in a ‘Remonstrance’ sent by Domhnall Ó Neill and other Irish leaders to Pope John XXII, they set out how they had sought help from Edward and had ‘unanimously established and set him up as our king and lord in our kingdom’.

Carrickfergus Castle was begun in the late 12th century by the Anglo-Normans, on the rock where Fergus, the first King of Scotland, drowned around 501. In 1315 Edward Bruce took the town and laid siege to the castle, and was reputedly crowned King of Ireland here. The castle eventually fell to the Scots in 1316. King Robert Bruce then joined Edward with a further 7,000 troops and began a campaign to try to take control of all of Ireland.

10 September 1315 - The Battle of Connor

After capturing the town of Carrickfergus, the Scottish army headed south to the important town of Dundalk, one of the seats of Anglo-Norman power in Ireland, along the way wreaking havoc on the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster. It is likely that the settlements at Dundonald, Downpatrick and Dundrum were razed at this time, while the impressive castle at Greencastle overlooking Carlingford Lough was captured.

Having razed Dundalk and much of the surrounding countryside, the Scottish army turned north and headed towards Coleraine where a Scottish pirate, Thomas Dun, ferried them across the River Bann.

At Connor, an important ecclesiastical centre near Ballymena, the Earl of Ulster, Richard de Burgh had gathered huge food stores for his men. Driven by hunger, Bruce’s army learned about these supplies, and marched towards Connor. A detachment of Bruce’s men, wearing the captured clothes of the men of one of de Burgh’s patrols, launched a successful attack on the Anglo-Norman encampment.

Early the following morning (10 September 1315) the Anglo-Normans attacked on the Bruce camp. However, the Scots had been expecting this, and as a decoy they had left their banners flying over their camp to create the impression that they were still there. De Burgh’s men were lured into the trap and were once again attacked by the waiting Scots.

Such was the confusion that Bruce’s army entered the town of Connor, took control of the food stores and seized the corn, flour and wine and carried it to their headquarters at Carrickfergus. One of the most important battles in medieval Ulster, Bruce’s victory at Connor left him as the effective master of the northern province of Ireland.

The Church of Ireland church in Connor stands on the site of its medieval predecessor, the cathedral of the diocese of Connor, which stood here in Edward Bruce’s time. The 19th-century historian George Benn observed: ‘Connor from its antiquity and ecclesiastical character – but still more from its association with the name of Edward Bruce – is, perhaps, one of the most interesting spots in the County of Antrim.’

14 October 1318 - Edward’s Death at Faughart: The Aftermath

Ultimately, the Bruce intervention in Ireland ended in failure. Despite Robert Bruce himself coming to Ireland in 1317 to support his brother, the Scots failed to conquer the entire island. After three-and-a-half years the campaign ended disastrously in defeat at the Battle of Faughart on 14 October 1318 with Edward Bruce himself killed in the fighting. Many of the leading men in the Scottish army were also killed.

The remnants of Edward’s army headed back towards Carrickfergus. On reaching the coast they boarded ships and returned to Scotland. It was the end of the campaign. There was to be no further Bruce-instigated invasion of Ireland.

Edward Bruce’s body was quartered with his head sent to Edward II. A strong tradition persisted, however, that he was buried in the old graveyard at Faughart. At different times in the nineteenth century there were suggestions in Scotland and Ireland that a permanent marker should erected at Faughart to commemorate him.

In the 1960s a flat stone was placed over what was believed to be Bruce’s grave. In recent years a new marble plaque was placed at the head of the grave which records, in English and Irish, ‘Edward Bruce, King of Ireland. Killed in Battle of Faughart, 14th October 1318.’

In terms of the importance of the story to Scottish history, the modern consensus amongst historians is that the invasion of Ireland ultimately served its purpose as Edward II of England was deflected by events in Ireland from his intended new landward invasion of Scotland. This give Robert Bruce the time needed to consolidate his position to be the rightful King of an independent Scotland. This was finally conceded by Edward III in the Treaty of Northampton a year before Robert’s death.

The flat stone on the reputed grave of Edward Bruce at the Hill of Faughart, County Louth.

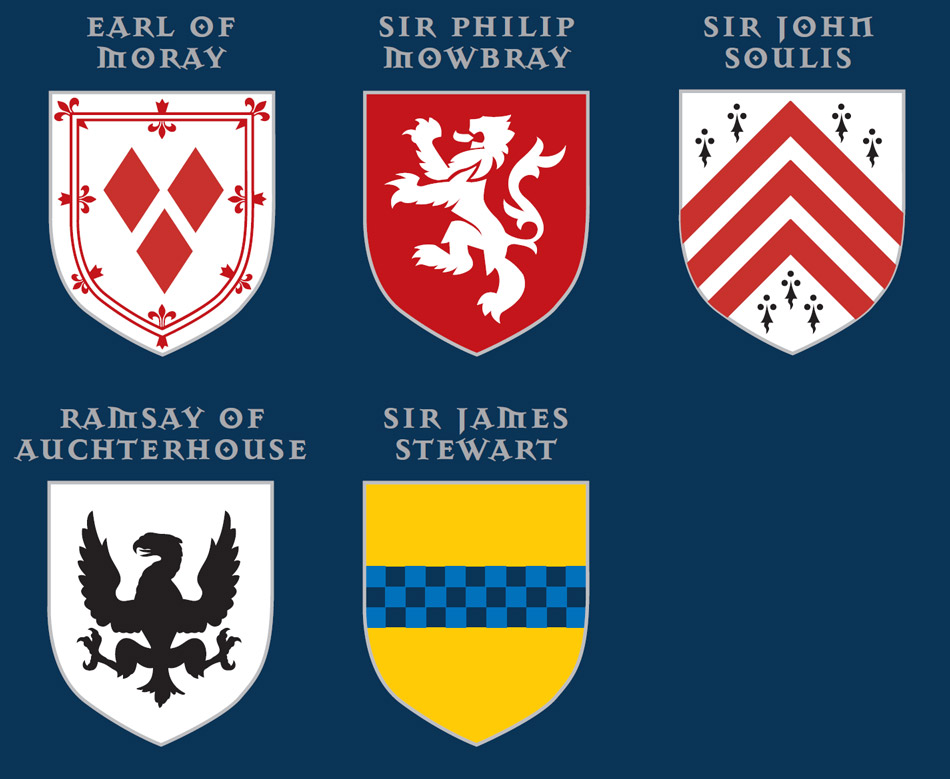

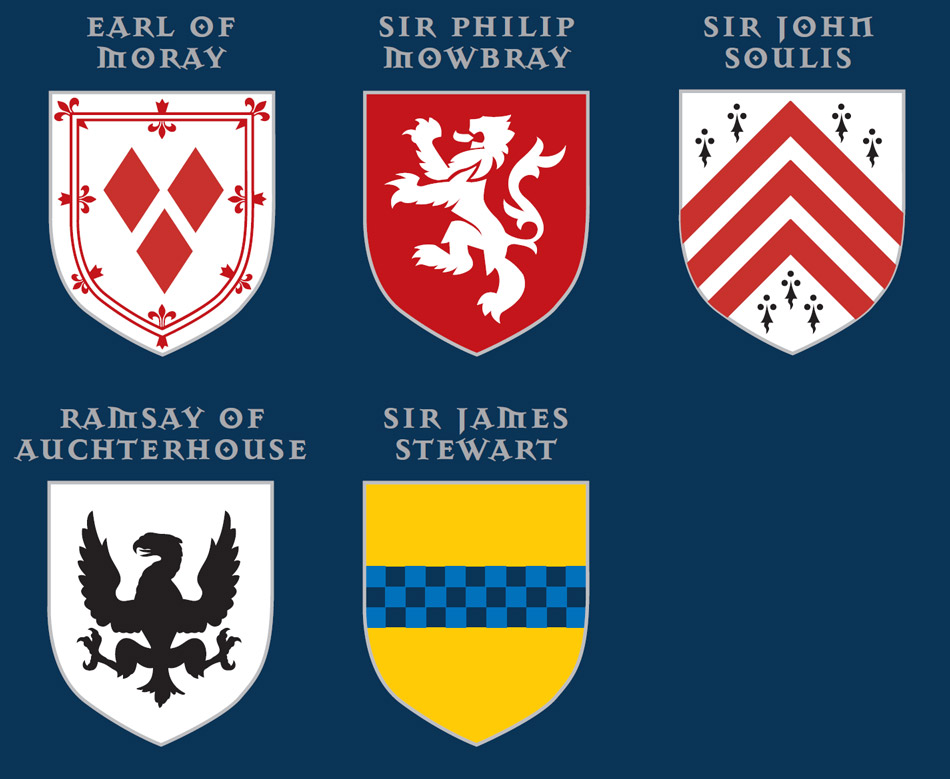

The Leaders of Edward Bruce’s Army

John Barbour, author of The Brus (1375), listed the principal knights who sailed to Ireland with Edward, all of whom were experienced soldiers and had close associations with the Bruce’s.

The most significant figure was ‘Earl Thomas’ Randolph, sometimes described as a nephew of Robert Bruce. A renowned knight, he commanded the Scottish vanguard schiltron at Bannockburn. He was to the fore in the raids into northern England that reaped immense booty and ransom monies used to pay for the Ireland venture. He was created Earl of Moray, probably in early 1315, just before he sailed for Ireland.

Among the others was the ‘good’ Sir Philip Mowbray – connected to the McDowalls of Galloway – who had been the warden of Stirling Castle when it was besieged by Edward Bruce from November 1313. After Bannockburn Mowbray was reconciled to the Bruce’s.

The ‘good’ Sir John Soulis, who was the son of one of the six Guardians of Scotland, joined Bruce early in his campaigns and was rewarded with lands in Dumfriesshire close to Carlisle.

The ‘doughty’ Sir James Stewart was the second son of James, High Steward and Guardian of Scotland. His father fought with Wallace at the bloody Battle of Falkirk. His elder brother Walter became the 6th High Steward of Scotland and married Robert Bruce’s eldest daughter Marjorie. Their son Robert became King Robert II – founding the Royal House of Stewart.

The ‘right able and chivalrous’ Ramsay of Auchterhouse was the Sheriff of Angus. He had previously fought with William Wallace.

Other prominent figures in Bruce’s army included Ailean Macruari, ‘King of the Isles’, and Alexander McDonald, ‘King of Argyll’. Macruari’s domain straddled both sides of the Sea of the Hebrides, including South Uist, Benbecula and Barra, while McDonald’s powerbase was on Islay and the adjacent coast of Argyll. Both of them were killed at the Battle of Faughart.

Leaders of Edward Bruce's Army

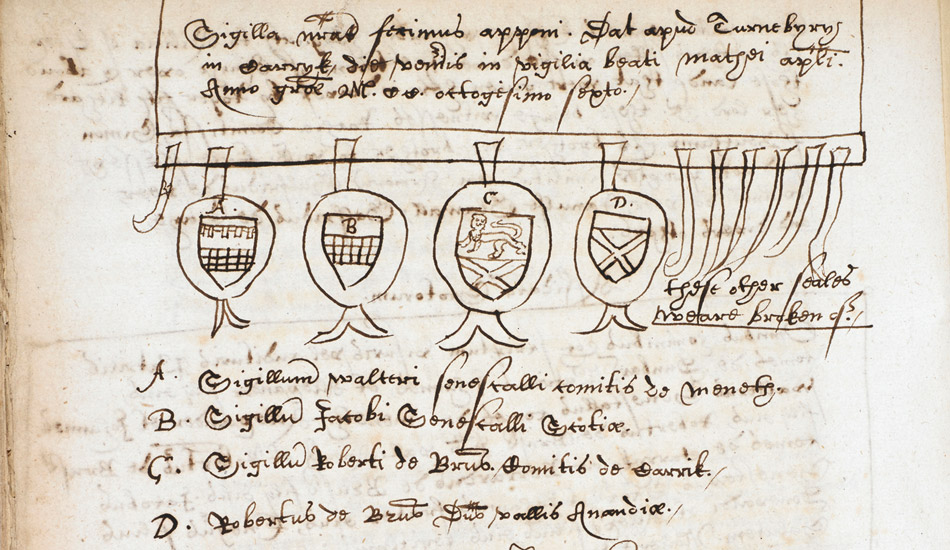

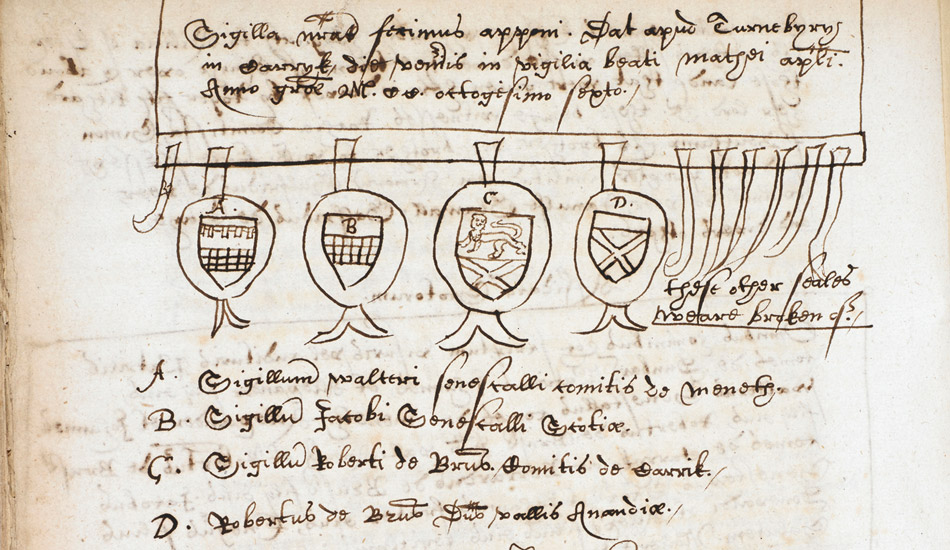

20 September 1286 - The Turnberry Band

On 20 September 1286 a number of Scottish nobles and Anglo-Irish lords gathered at Turnberry Castle on the west coast of Ayrshire. Among them were Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale, and Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, respectively, grandfather and father of the future King Robert I.

The agreement drawn up by these men has become known as the Turnberry Band (or Bond). Under it the Scots agreed to support two Anglo-Irish lords, Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, and Thomas de Clare, in their power struggles in Ireland. It has also been argued that the Turnberry Band formed the basis of the Bruce claim to the crown of Scotland.

Turnberry Castle had become the home of the Bruce’s following the marriage of Robert Bruce (father of King Robert) to Marjorie, daughter of Neil, Earl of Carrick, c. 1272. Robert was her second husband, her first having died while on a crusade. Marjorie was descended from Niall Ruadh Ó Neill, king of Tyrone, through which King Robert and his brother Edward could claim Gaelic Irish ancestry.

In the early twelfth century King John granted the first Earl of Carrick lands in County Antrim stretching from Larne to Glenarm. When Edward Bruce led his army to Ireland in 1315, they arrived in an area over which his brother Robert was feudal lord.

A drawing of the Turnberry Band, showing four seals: A. Walter Stewart, Earl of Menteith, B. James Stewart, Guardian of Scotland, C. Robert Bruce, Earl of Carrick, D. Robert Bruce, Lord of Annandale. Image courtesy of The British Library Board, Lansd. 229 fol. 111.

Domhnall Ó Neill - King of Tyrone

Of vital importance to Edward Bruce during the campaign in Ireland was the support he received from his Irish allies. The leading Gaelic Irish figure in Ulster in the early fourteenth century was Domhnall Ó Neill, king of Tyrone, a distant cousin of the Bruce’s.

The son of Brian Ó Neill, king of Tyrone, Domhnall was probably a child when his father was killed in battle with the Anglo-Normans at Down in 1260. Following the death of his cousin, Aed Buide Ó Neill, in 1283 Domhnall seized the kingship of Tyrone.

For over 30 years prior to the arrival of the Bruce army in Ireland he had been involved in a power struggle with the de Burghs. From 1310, Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, renewed his efforts to undermine Domhnall’s authority by drawing away from him some of Ó Neill’s allies, and rewarding his rivals.

Finding himself increasingly threatened by de Burgh, Domhnall looked to Scotland and to Robert Bruce for assistance, encouraging the victor at Bannockburn to send a Scottish army to Ireland to fight the Anglo-Normans. After Edward Bruce and his army landed in County Antrim, Domnhall and other Irish leaders joined him and proclaimed him king of Ireland.

Domhnall Ó Neill would prove to be one of Edward’s most trusted Irish allies throughout the time he was in Ireland. Domhnall fought with Edward Bruce at Faughart on 14 October 1318 and though their combined forces were heavily defeated by the Anglo-Normans, Ó Neill was able to escape. He remained king of Tyrone until his death in 1325.

Enjoying excellent views of the surrounding countryside from its hilltop location, Tullaghoge, County Tyrone, was the place of inauguration of the kings of Tyrone. It is possible that Edward Bruce and his army passed this site on their march to Coleraine in the summer of 1315. (Photograph courtesy Dr Colm J. Donnelly.)

Robert Bruce’s Visits to Ireland

Each clear day that Robert Bruce looked out across the North Channel from his home at Turnberry Castle he could see lands over which, through his mother, he was the feudal lord. Furthermore, he was married to a daughter of the Earl of Ulster. As one historian has written: ‘Ireland cannot have seemed in any sense a foreign or unfriendly country to Robert Bruce, married to an Irishwoman and inheriting more than a century of family connections with Ulster.’

Following the Scottish victory at the Battle of Connor, Edward invited his brother Robert to join him in Ireland. Robert, no doubt delighted by Edward’s success, declared he would go ‘blithely’ to see ‘the affair of that countre and of thair war’. It was quite a few months, however, before Robert travelled to Ireland.

The Irish annals record that in the summer of 1316 Robert assisted Edward in besieging Carrickfergus Castle. At one point 60 Scots were taken hostage, eight of whom died from starvation. These eight were eaten by the starving soldiers in the castle. Eventually, the castle surrendered to the Scots.

In the early weeks of 1317 Robert and Edward set out on a major expedition against the Anglo-Normans. Having marched to Dublin, but not attacked it, the Bruce army conducted a campaign of devastation, destroying the estates of the leading Anglo-Norman lords in Ireland. Marching to Limerick the Scottish army was responsible for ‘laying waste the entire country’. The campaign caused huge destruction but achieved very little for the Bruces. In May 1317 Robert returned to Scotland and would not reappear in Ireland during the remainder of his brother’s campaign.

Even after the end of the Bruce campaign in 1318 Robert continued to maintain an interest in Irish affairs. Towards the end of his life, he is known to have travelled to Antrim on two occasions – visiting Glendun in 1327 and Larne the following year.

In a beautiful setting with excellent views of the Mourne Mountains and Carlingford Lough, this mainly 13th-century castle was captured by the forces of Edward Bruce in 1315/6. In 1328, Robert Bruce proposed holding a meeting here to agree a peace treaty between Scotland and Ireland.

Richard De Burgh – Earl of Ulster

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, Ireland was divided between areas were the Anglo-Norman lords held sway and regions that were controlled by powerful Gaelic Irish families. In Ulster the Anglo-Normans were strongest in the east of the province, especially in the coastal regions of counties Antrim and Down.

The most powerful Anglo-Norman lord was Richard de Burgh, the Earl of Ulster – Robert Bruce’s father-in-law – who was described in the Irish annals as ‘the choicest of all the foreigners of Erin’. On the eve of the Bruce invasion of his earldom he had extended his authority along the north Derry coast and the Inishowen peninsula, building the impressive castle of Northburgh (or Greencastle) in County Donegal. He was regularly involved in Scottish affairs, though did not go to Scotland in the spring of 1314, when summoned to do so by Edward II, and so avoided the Battle of Bannockburn.

The arrival of the Scots in Antrim seems to have taken the Anglo-Normans by complete surprise and Richard de Burgh himself was in the west of Ireland when the landing took place. Eventually, he assembled an army and pursued the Scots northwards towards Coleraine, before engaging them in battle at Connor on 10 September 1315.

This battle resulted in a decisive victory for the Scots and afterwards de Burgh was forced to withdraw to Connacht. As a result of the Bruce campaign his territories were left devastated, while his seats of power were captured and, in some cases, destroyed. He was described as ‘a wanderer up and down Ireland, with no power or lordship’. To compound his misfortunes, he was imprisoned for a time in 1317 when it was suspected that he was conniving with the Scots. He died at Athassel, County Tipperary, in 1326.

Strategically positioned at the mouth of Lough Foyle, Greencastle (also known as Northburgh), was built by Richard de Burgh, Earl of Ulster, in 1305 at a time when he was extending his authority in the north of Ireland. It was captured by Edward Bruce in 1316.

Literature and The Bruce Campaign

In the centuries since 1315, the story of Edward Bruce’s campaign in Ireland has been told many times, by poets, historians and novelists.

The main source of information on the campaign from the Scottish perspective is the account given by ‘Master Johne Barbour’, one time Archdeacon of Aberdeen. He was well educated, had travelled extensively and was active in the court of King Robert II. The factual content of his metrical epic narrative – The Brus, The History of Robert the Bruce King of Scots of 1375 – can be assumed to have been compiled from a mixture of living testimonies and passed down memories and is the earliest known account to have survived.

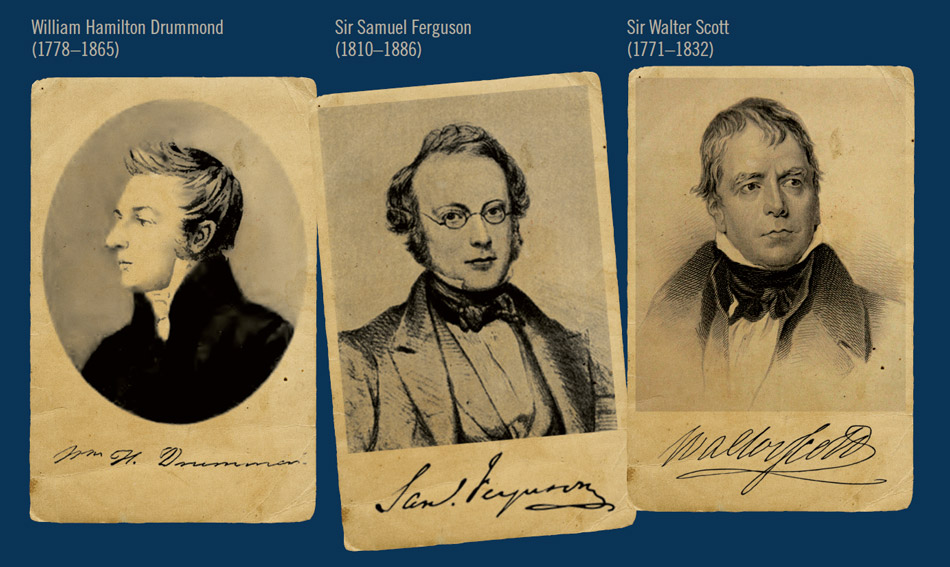

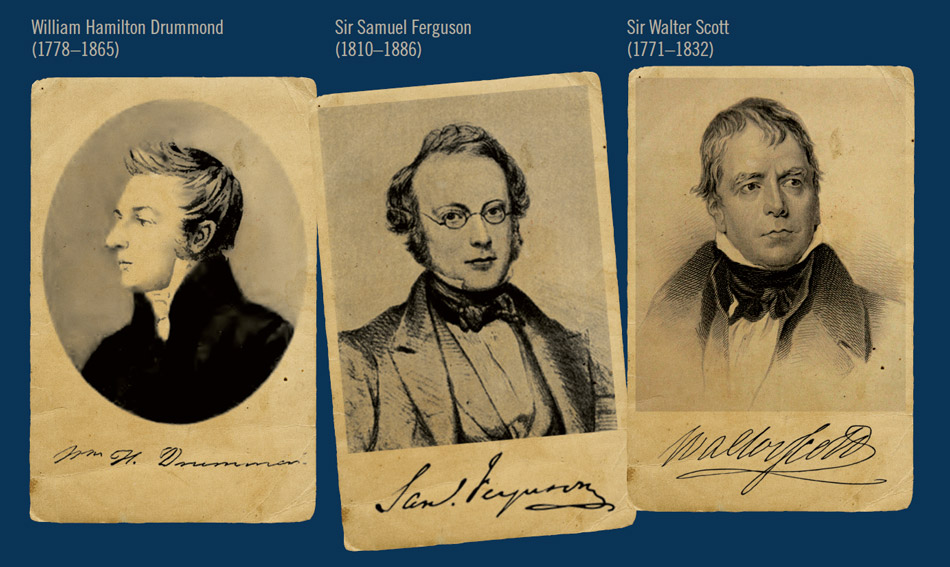

In 1826, the Larne-born poet William Hamilton Drummond published his 128-page Bruce’s Invasion of Ireland, a Poem. Another academic with south Antrim origins, Sir Samuel Ferguson, wrote a historical story in 1833 about the Ó Neills, set 500 years earlier in 1333, during the period after the Bruce campaign. Entitled The Return of Clandeboye, it touches on the Ó Neill alliance with the Bruce’s.

In the early 1800s, Sir Walter Scott did more than any other writer to popularise the key figures and events from Scottish history. In his famous collection, Tales of a Grandfather, he wrote the following:

You will be naturally curious to hear what became of Edward, the brother of Robert Bruce, who was so courageous and at the same time so rash. You must know that the Irish at that time had been almost fully conquered by the English; but becoming weary of them, the Irish chiefs, or at least a great many of them, invited Edward Bruce to come over drive out the English and become their king. He was willing enough to go, for he had always a high courageous spirit, and desired to obtain fame and dominion by fighting. Edward Bruce was as good a soldier as his brother, but not so prudent and cautious; for, except in the affair of killing the Red Comyn, which was a wicked and violent action, Robert Bruce, in his latter days, showed himself as wise as he was courageous. However, he was well contented that his brother Edward, who had always fought so bravely for him, should be raised up to be King of Ireland.

Left: William Hamilton Drummond (1778–1865)

Middle: Sir Samuel Ferguson (1810–1886)

Right: Sir Walter Scott (1771–1832)